Am 27.11.24 stellte ich einen ausnehmend hässlichen Maskentyp vor.

Ich begegnete ihm zum ersten Mal an einem Stand, dessen Angebot über Kinshasa aus kongolesischen Dörfern kommt, diese Maske an der oder über die angolanischen Grenze. Nach der Sicherheitslage im Kongo und Runner wechseln die vorherrschenden Stilregionen.

Beschreibung

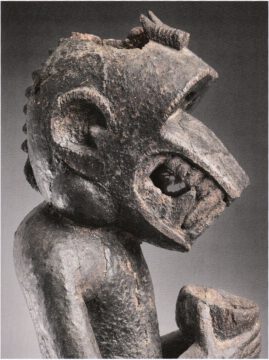

Chokwe Katojo IMG_7027

Vom zerrissenen und verdreckten roten Textilnetz weitgehend befreit, kommt der markante eiförmige aufgedunsen wirkende Kopf zur Geltung mit dem böse schimpfenden Mund über einem aggressive vorstehenden Kinn wie ein Rammbock. Die lächerlich kleine gebogene Nase, suggeriert im ersten Moment einen Nasenbeinbruch. Die runde Kappe schließt die geschnitzte Form nach oben ab. Die Kappe hat eine rote Fehlstelle; trotzdem muss die stumpfe Schlammpatina keine nachträgliche Veränderung sein. Schwärzlich rote Schlammpatina mit anhaftenden roten Staubpartikeln.

Als Teil eines einheimischen Kults waren wenigstens die Ohren geschmückt; davon ist aber nur auf einer Seite ein Stück Schnur erhalten.Dass nur zwei hölzerne Zahnstifte, statt Metallstifte im Oberkiefer stecken, könnte auf Ersatz hinweisen.

Als Teil eines einheimischen Kults waren wenigstens die Ohren geschmückt; davon ist aber nur auf einer Seite ein Stück Schnur erhalten.Dass nur zwei hölzerne Zahnstifte, statt Metallstifte im Oberkiefer stecken, könnte auf Ersatz hinweisen.

Die Maske hat nichts von der Lebendigkeit oder Würde, die vor allem die Maskengesichter der Chokwe auszeichnen. Die aufgeschwemmte, leere Glätte der Wangen und Stirnen! Die Augenhöhlen, die an technische Sichtluken erinnern! Die bewusst verkleinerten Ohren und Hakennasen! Die fehlenden Lippen am bis zu den Zähnen aufgerissenen Mund!

Dieser negative Typ taucht heute wohl nur in Museumsdepots und in der Fachliteratur auf. Ein solches Fachbuch ist „CHOKWE!- Art and Initiation Among Chokwe and Related Peoples“, von Manuel Jordán in Kooperation mit mehreren amerikanischen Museen herausgegeben und 1998 bei Prestel erschienen.

Textauszug zur kultischen Bedeutung der Maske „Katoyo“

Im Kapitel „Engaging the Ancestors: Makishi Masquerades....“( „die Ahnen ins Boot holen….“) stellt Manuel Jordan vorbildliche und negative Maskentypen vor. Was er auf S.73 schreibt, übersetze ich mit Google (korrigiert):

( ….) Während Chihongo und Chisaluke männliche Vorbilder von gesellschaftlichem Ansehen, Macht, Reichtum und spirituellem Einfluss darstellen, stehen andere männliche Charaktere für Werte, die gesellschaftlich als negativ angesehen werden. Ein Likishi-Charakter namens Ndondo hat eine einfache Gesichtsmaske, die normalerweise aus Faser und Harz besteht, und sein Kostüm besteht aus zerlumpten Tüchern und einem geschwollenen Bauch. Ndondo soll hässlich sein und sich dumm verhalten. In mukanda-bezogenen Dorfaufführungen kriecht Ndondo auf dem Boden, bettelt um Geld und sagt idiotische Dinge. (mukanda = männliche Initiation mit Beschneidung der Vorhaut)

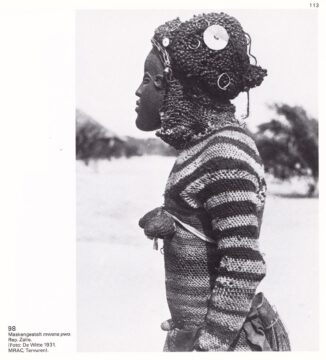

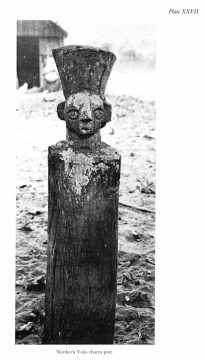

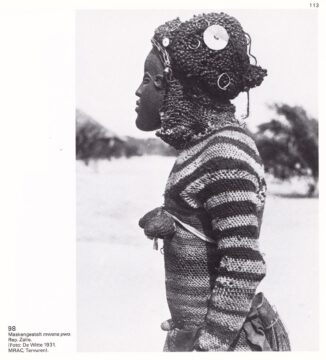

Zaire – Masken Figuren, Basel 1986, no.98 ‚mwana po‘ (Pwewo) 1931

Neben der schönen, wohlerzogenen Pwevo, einem Muster an Kultiviertheit, verkörpert Ndondo einen Menschen mit schlechten Manieren. Seine Darbietung wird als humorvoll und unterhaltsam wahrgenommen, aber sie klärt das Publikum über Verhaltensweisen auf, die gesellschaftlich nicht akzeptabel sind.

Die von Chokwe und verwandten Völkern geschaffenen und durchgeführten Maskeraden schließen auch andere Charaktere ein, die soziale und kulturelle Prinzipien repräsentieren, die im Gegensatz zu ihren eigenen stehen. Katoyo ist eine Maske, die von den Chokwe geschaffen wurde, um eine weiße Person darzustellen (Tafeln 76, 78-80). Wie Ndondo hat diese Maske karikaturhafte Züge. Katoyo-Masken, die aus Fasern und Harz modelliert oder aus Holz geschnitzt werden, übertreiben oft die Gesichtszüge von Weißen durch spitze Nasen, „übermäßige“ Gesichtsbehaarung oder große, krumme Zähne. Die Stirn der Katoyo wird manchmal als verlängerte Kappe aufgefasst, eine Anspielung auf die Form eines portugiesischen Militärmütze oder -helm. (Fig. 79) Ironischerweise dokumentierten einige europäische Entdecker Katoyo-Maskierte, ohne zu erkennen, dass diese weiße Ausländer parodierten.

In der Vergangenheit halfen Katoyo-Auftritte den Chokwe-Gemeinschaften wahrscheinlich dabei, mit der Idee des Neuen oder dem, was ihnen fremd war, umzugehen. Heute verspotten die Maskeraden der kongolesischen Chokwe, südlichen Lunda, Mbunda, Luvale und Luchazi weiterhin solche „Außenseiter“ wie ihre Lozi- und Nkoya-Nachbarn. Masken, die „die anderen“ darstellen, verstärken ein Gefühl kultureller Identität, indem sie unangenehme oder absurde Aspekte des Verhaltens benachbarter Völker definieren. Im Fall der Lozi und Nkoya ist der wichtigste kulturelle Unterscheidungsfaktor, dass sie kein Mukanda praktizieren. Da Mukanda, einschließlich des Schlüsselritus der Beschneidung, für den Eintritt ins Erwachsenenalter bei den Chokwe und verwandten Völkern, erforderlich ist betrachten die Chokwe Lozi- und Nkoya-Männer, die nicht beschnitten sind, als sozial und kulturell „mangelhaft“ – nicht als Erwachsene.

Ngulu Typen

Das große Repertoire an Makishi-Masken, die von Chokwe und verwandten Völkern geschaffen wurden, umfasst auch Darstellungen von Tieren und einer großen Anzahl mehrdeutiger Kreaturen. Ngulu, das Schwein, tanzt normalerweise neben Pwevo und verhält sich unberechenbar und „töricht“, um das Bild menschlicher Anständigkeit zu verstärken, das durch die weibliche Vorfahrin charakterisiert wird (Pk. 81-83). (….)

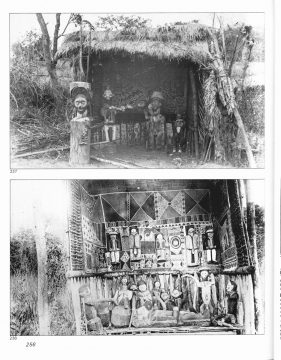

Aus dem großen Repertoire zeigt das Buch nur eine Handvoll Abbildungen, begleitet von ein paar improvisiert wirkenden Hinweise. Beide zeige und übersetze ich hier:

.

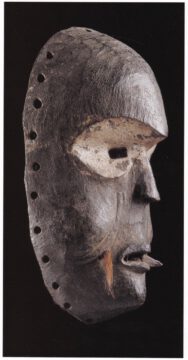

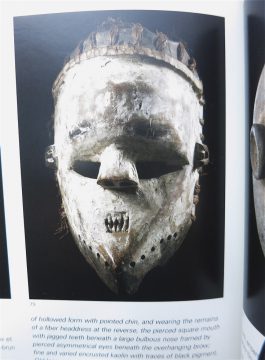

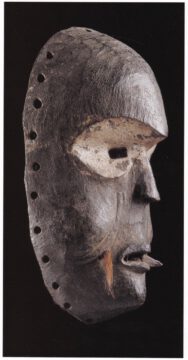

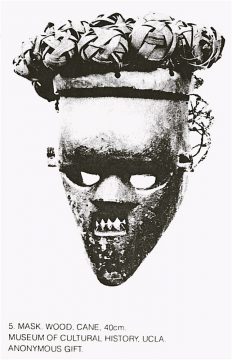

Jordan Chokwe! no.76 Katoyo

Zu 76 19.Jh. 23,2 cm; reiche Oberflächenpatina, die auf ausgiebige Verwendung im Feld hinweist, bevor sie gesammelt wurde. Sie weist noch einen großen spitzen Metallzahn, Gesichtshaar und weißen Ton um die Augen auf. Weiß wird mit den Knochen der Vorfahren assoziiert, und wenn weiße Kreide um die Augen gelegt wird, bezieht sie sich auf die scharfen und durchdringenden Blicke der Vorfahren.

An anderer Stelle im Buch (fig.87 „Kalebwa„) bezeichnet der spitze zentrale Zahn explizit einen aggressiven Ahnengeist, der die mukanda (Initiation) gegen Hexer schützt und durch Verjagen der Frauen die Spannungen zwischen den beiden Geschlechtern zeitweise verschärft.

.

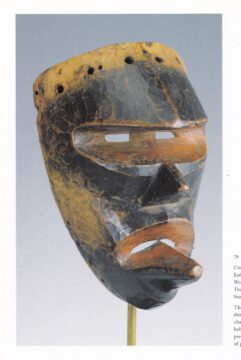

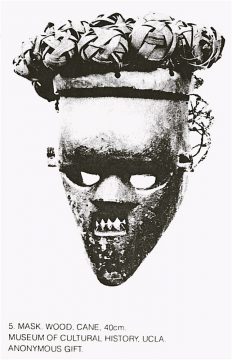

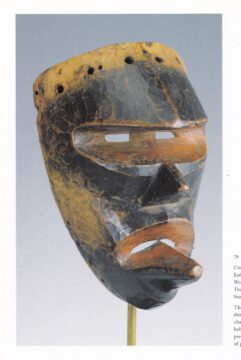

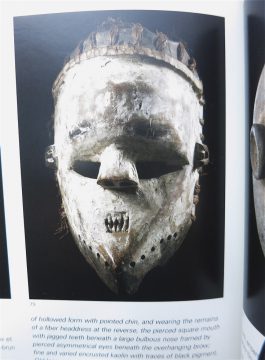

Jordan Chokwe! no.78 Katoyo

zu 78 Anfang des 20. Jahrhunderts, 17 cm hoch; Die spitze Nase und die übertriebenen Lippen karikieren einen europäischen Charakter. Bei öffentlichen Aufführungen half Katoyo den Chokwe-Gemeinden, mit der Anwesenheit von Fremden und ihren neuen Formen politischen Einflusses zurechtzukommen.

Jordan Chokwe! no.79 Katoyo

Zu 79 Die Kappe imitiert die Helme der portugiesischen Offiziere …. Knochen oder Stöcke wurden auf den Mund gelegt, um die ‚übermäßige‘ Gesichtsbehaarung der Europäer zu kommentieren.

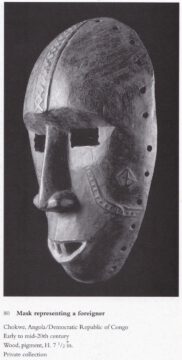

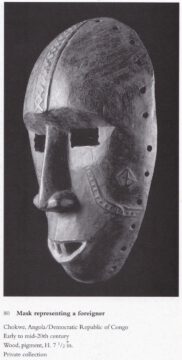

Jordan Chokwe! no.80 Katoyo

Zu 80 Von Anfang bis Mitte des 20. Jahrhunderts; lange Nase und große Zähne …. verspotten die Gesichtszüge der Europäer. Skarifikationen (Schnittnarben) betonen das Konzept, dass … es sich dennoch im Wesentlichen um Ahnenwesen handelt. Im Rahmen der Mukanda-Initiation wurde Katoyo zusammen mit Chihongo getanzt, damit das Publikum die schlechten Manieren und Haltung von Katoyo mit den kraftvollen Eigenschaften des männlichen Chihongo-Vorfahren vergleichen konnte.

Der Fremde wird also durch eine Fratze repräsentiert. Disproportionen an jedem Detail: niedrige Stirn wie ein Helm, eng stehende Äuglein, tiefsitzend, aber nach ‚afrikanischem‘ Code schamlos offen, kurze Hakennase, endlos lange Wangenpartie und Kinn. Hängende Mundwinkel, wie eine Hexe im europäischen Puppenspiel.

Das aufgerissene Maul meiner Masken mit zwei spitzen Zähnen scheint verächtliche Worte auszustoßen oder einen primitiven Befehl zu brüllen, so wie KZ-Überlebende, um mir in Polen ihre ‚dürftiges‘ Deutsch zu demonstrieren, oft eine kurze gebrüllte Schimpftirade der Wärter im O-Ton wählten.

Dieses Feldfoto von einer Maskerade der Yoruba westlich des Niger, rund achtzehnhundert Kilometer nördlich am Atlantik verblüfft mich durch die Physiognomien.

Auch hier haben die Gesichter eine aufgedunsene ‚hohle‘ Form, der Mund ist weit unter die Nase gerutscht. Die moderne Kostümierung und die rot geschminkten Lippen der Frau können ihre Geisterhaftigkeit nicht verbergen. Zufall?

Ist etwas dran an diesem Verdacht? Frobenius-Bibl. Af I 1826 Yoruba Egun-Maske

31.5.25. Die Reißzähne der Maske lassen mir keine Ruhe! Kommentar:

Bei der ersten „Katoyo“-Maske im November 2024 folgte ich unkritisch Manuel Jordan, einem ausgewiesenen Experten für die Region, in seiner Deutung der Katoyo primär als Karikatur der Europäer. Für die Gegenwart schien er im Text die Behauptung aber wieder zu relativieren, da er auch die unbeschnittenen Nachbarn, die Lozi und Nkoya, als Zielscheibe des Spottes erwähnte. Darüber hinaus erwähnte er ein „großes Repertoire an Makishi-Masken …., das auch Darstellungen von Tieren und eine große Anzahl mehrdeutiger Kreaturen“ umfassen sollte. Mit der erzieherischen Rolle des „Ngulu“, des lächerlichen Warzenschweins, das die edle Frauenmaske Puevo bei Auftritten begleitet, war ich bereits vertraut.

Die beiden eingesetzten spitzen Eckzähne der Katoyo blieben mir ein Rätsel. Sie bedeuteten vielleicht mehr als die Verstärkung trivialer physischer Hässlichkeit. Eine zweite Katoyo brachte im Mai einen frischen Impuls. Sie schien einfach besser zu den gebotenen Beispielen im Buch zu passen. Ich komme darauf bald in einem zweiten Blogbeitrag (LINK) zurück.

Eine Abbildung der bekannten langen Reisszähne männlicher Paviane in dem Buch „Baule Monkeys“ ( Bruno Claessens, Jean-Louis Danis; Mercatorfonds 2016 ) liefert mir nun einen – hypothetischen – Schlüssel.

Die Künstler der Baule in Westafrika sind für ihre formal ausgefeilten Maskenskulpturen ebenso berühmt wie die der Chokwe. Auch sie pflegen einen kontrastierenden Kult grob gehauener und hässlicher Affenfiguren. Ich übersetze aus dem Abschnitt Zoomorphe Absicht (S.115):

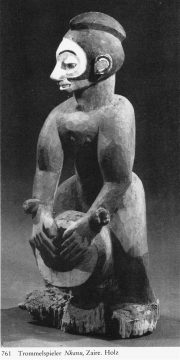

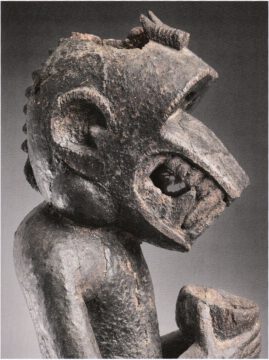

baule monkeys 2016, p.130 fig.84 (Detail eines Schalenträgers)

Da die Baule-Bildhauer in der Lage waren, hochfeine männliche und weibliche Figuren aus Holz zu schaffen, brachte der grob behauene Aspekt der Schalenträger ihren bedrohlichen Charakter absichtlich zum Ausdruck.

Im Gegensatz zu Naturgeistern wie asye usu, musste die amuin nicht mit seinem Bildnis „beschwichtigt“ werden. Die mächtigen und gefährlichen Figuren, die diese Geister verkörperten, sollten Angst, Ehrfurcht und Abscheu einflößen. Ihr wesentliches Merkmal war ihr furchteinflößender Aspekt. Als Vertreter einer wankelmütigen übernatürlichen Macht sollten sie diejenigen, die sie erblickten, mit Ehrfurcht und Schrecken erfüllen.

Wie wir in der afrikanischen Kunst sehen, wurden bestimmte Verhaltensweisen, die bei Tieren beobachtet wurden, gezielt in Masken und Figuren materialisiert. Baule-Bildhauer fanden ein Vorbild in den Pavianen, die ihr Gebiet in großer Zahl heimsuchten. Wie Naturgeist amuin waren Paviane mächtig und konnten töten. Sie wurden wegen ihrer Beweglichkeit, Stärke und langen, scharfen Reißzähne gefürchtet. Ihr ausdrucksstarker Kopf, ihre lange Schnauze und ihre aggressiven Augen waren ideal, um die Wahrnehmung eines gefährlichen Dämons zu vermitteln.

baule monkeys 2016, p.129 fig.83 baboon

Paviane leben in großen Gruppen am Boden. Paviane, die gelegentlich Felder überfallen und große Zerstörung anrichten, Ackerland zerstören und Chaos anrichten, können als Metapher für sozialen Zwiespalt dienen. Paviane können grimmige Kämpfer sein, die mit ihren kräftigen Eckzähnen tiefe Wunden zufügen können. In der Gruppe sind sie noch gefährlicher; wird einer bedroht, reagieren die anderen möglicherweise mit einschüchternder Aggression, allerdings eher durch Posieren als durch einen tatsächlichen Angriff. Die Baule halten sie für gefährlich: Allein oder unbewaffnet würden sie sich keinem Pavian stellen.

Mantelpavian-Männchen in der Gruppe. Wikip.

Allerdings beschützen Paviane ihre Jungen sehr und zeigen große Solidarität. Diese zwiespältigen Assoziationen könnten erklären, warum der Pavian diese Art der Abbildung inspirierte. (…) Die Tiergestalt solcher Figuren sollte hauptsächlich deren Wildheit und Fremdheit vermitteln.

Der Charakter dieser in Afrika verbreiteten Raubtiere eignet sich als Vertreter wilder und negativ bewerteter Mächte. So wird mir die erste Katoyo-Maske der Chokwe im Kongo und Angola allmählich immer ‚äffischer‘: die niedrige Stirn mit tiefliegender Nasenwurzel; die kleine flache Nase und die verlängerte Schnauze zwischen gerundeten Backentaschen fallen besonders auf. Und warum sollte der breite Bart eines alten Pavian nicht aggressiv zugespitzt werden, das bekannt aggressiv aufgerissene Maul nicht angedeutet werden? Die vermissten Ohren könnten ja bloß vom Backenbart verdeckt sein. ….

Vielleicht waren es bloß einzelne Anleihen aus der Tierwelt, aber vielleicht trug diese Maske auch einen eigenen Namen und hieß vielleicht gar nicht „Katoyo“.

Jedenfalls ging von der Fremdheit und Wildheit der kolonisierenden Fremden eine weit größere Gefahr aus als von jedem tierischen Mitbewohner. Diese Masken und ihre Tänze lassen sich als kulturelle Widerstandshandlungen bewerten.

Und die Opferrolle der Chokwe?

Wir haben keinen Anlass, die Chokwe zu Opfern zu stilisieren. In den 1880er Jahren vertrieben ihre brutal vorgetragenen Raubzüge ihre nördlichen Nachbarn wie die Pende („Das war das 20. Jh. der Pende“) weit nach Norden und zwangen kleinere wehrhafte Völker wie die Salampasu zu tiefgreifenden Veränderungen ihrer Sozialstruktur („Willkommen bei den Salampasu„). Wenn ich jetzt den berühmten abschreckenden Maskentyp der Salampasu sehe, kommt mir der Gedanke: Die ‚Identifikation mit dem Angreifer‘ hat auch nichts geholfen.

AA 22 1988 Cameron p.38 40cm, mask UCLA

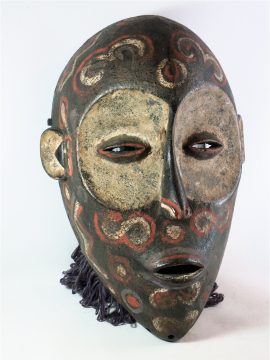

Sothebys Sept.2002-no.79 Initationsmaske

.

Die von Jordan erwähnte Zelebrierung der Verachtung für ‚unbeschnittene‘ Nachbarn, „Außenseiter“ wie ihre Lozi- und Nkoya-Nachbarn (S.73), in der Phase der Kriege während der ‚Entkolonialisierung‘, illustriert vielleicht das unter den Chokwe fortlebende Gewaltpotential .