NEW EDITION 07.03.2019 (First edited 31.12.2018) WITH DEBATE AND 4 PHOTOS BY MARVIN GOERTZ Link to the German Version (since 28.12.18)

Preliminary Note

„There is so much malnutrition in the Bandundu Province that people have not been dancing much since 1990“ (Z.S.Strother, 2007) „Although the masking situation in the Bandundu was unhealthy in 2007, in 2017-18 there were a number of (large) mukanda camps in the Kasai“ (Z.S.Strother, Jan. 2019)

Once upon a time …. The Pende liked dance performances like crazy. Social event! The singers and their messages, the creative energies and vitality of the dancers and drummers, the newly invented masks in their costumes. All that kept the communities together, more or less in opposition to the colonial administration and the sour sadness of the Christian missionaries, to the abuse of power by chiefs, their greed and stupidity … and that through a whole chaotic century. In an earlier post I’ve retold that story ( in German: Link). And of course dance performances were for common pleasure! Is the festival over now?

I got my informations mostly from publications of Zoé Strother, an American art historian – and in my view anthropologist as well – who lived from 1986 to 1989 with the Pende. Since her fundamental essay „Inventing Masks“ thirty years have passed. The youngest generation of carvers 1989 is now old. Who is still active? What are their ’business plans’ now? Do they already live in Kinshasa?

This year I bought a strong Pende mask from some middleman. In my eyes it was no beauty, rather a successful caricature. I sent some photos to New York, and Zoé S. Strother answered:

„I’ll surprise you, it’s a strong and clean representation of a hyper-male character (protruding forehead; protruding eyes; peanut-like silhouette with marked cheekbones.) Very nice! Pulling the nose out like putty is something I’ve seen. The handling of the teeth (normal, not aggressive) is again something one sees. The whole is in the style of a deceased dancer / sculptor but I think this carver has more talent. Of course, what I can’t see is whether it fits well over the face and I’m not saying that it was ever used, but the carver has talent and self-discipline. „

What an incentive to search for mask type and personal style! But a delicate task! Renewed consultation of „Inventing Masks“ (1998) has been helpful.

Had Léon de Sousberghe overlooked something in the post-war style of ‚Katundu‘ Pende?

Léon de Sousberghe, the undisputed authority for L’Art Pende, complained in 1958 that in the chefferie Katundu individually designed realistic face masks had displaced the standardized mask types with a long beard (39, note). With two exceptions – Tundu, the clown, and Mbangu with his epileptic grimace (34) – he could no more identify individual masks. Moreover his informants merely feigned their knowledge. He reproached the carvers for their lack of talent or inspiration to work out typical characteristics. At the most some masters produced ‚excellent sculptural quality‘, but once they had found their form, they applied it to all types (34). A specific mask could only be identified by details of the dancer’s hairstyle and attire, by poses and dance steps (32). The face was identical, for a woman or a man, old or young. It would often disappear under their accessories anyway. (35/36) Old characters survived in such an ensemble under atypical masks, with the exception of the already mentioned Tundu and Mbangu. (Link to the first blog two years ago, in German)

When the doctoral student Zoé S. Strother arrived in the carver village of Nyoka-Munene towards the end of her three years field stay in 1989, the artists – dancers and carvers alike – accepted to be thoroughly observed and interviewed. Their new practice was established in all its facets and people could tell about established practice.

A ‚physiognomic grammar‘ used by carvers, dancers and spectators

Strother learned how masquerades, their themes and forms renewed themselves, and what role the local „physiognomic grammar“ (153) played in composing matching mask faces. According to their logic, each master sought to find his distinctive interpretation of the ordered mask type, and that was not an anonymous ‚form‘ as de Sousberghe had lamented.

Above all, that carved physiognomy expressed individual characters in relation to gender sterotypes.

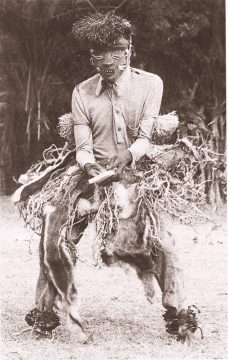

In cultures where women are considered ’cooler’, a ’hot’ dance performance is equated with broad-legged posture, sweeping gestures, unexpected directional changes, whirling movements, tempo, and energy bursts. For the Pende, a ’cool’ dance is slower and is realized either on the spot or through a stylized ‚walk‘. (136)

Three master carvers, Zangela, Mashini and Koshi, described the ideal of the ‚hyper-masculine‘ mask as follows: forehead protruding like a billy goat’s, eyebrow bushy, large eyes, and dangerous gaze, well open. The nose is large like a big horn with large hole. Mouth pouts like speaking in anger. (133)

Connoisseurs among the Pende insisted on foreseeing the kind of dance in the face of the mask: The more the dance is ’hot’, the more pronounced are the volumes of the face. The visual equivalents for broad erratic movements of dance are protruding masses. The finer the gestures are, the smaller and more sophisticated are the facial features. (137)

I should mention that representations of a chief, whose role requires self-restraint and discipline in public, are also in line with the ‚cool‘ type of women. Similarly, the representation of the conservative village fortune teller (Nganga Ngombo or Nganga Ngombo Mukhetu) is characterized by restraint (Link to Blog „Skeptische Klienten …“ in German).

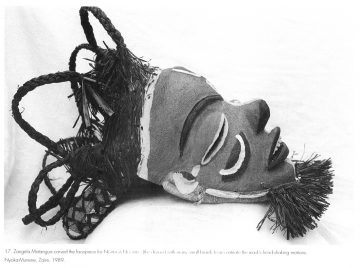

For example, a male and a female nganga carved by Zangela Matanga exude a high degree of restraint:

Insight and Artistry.pl.8 NgangaNgombo Mukhetu, sculpted by Zangela Mantangua of Nyoka-Munene. Photo by Z.S.Strother 1989

The physiognomic differences to my mask face are considerable: first the unobtrusive foreheads, generally harmonious proportions, such as the placement of the slightly open expanded mouth, full lips, a beautiful upper row of teeth, long eye slits and elegantly curved eyebrows. – Zangela’s style was generally less striking, perhaps even ‚psychological‘. Strother says of him on the occasion of an ‚ugly‘ female mask: „He solicits our compassion in understanding the forces that might transform a beautiful young woman into a crone made crotchery through a sense of ill-usage.“ (153).

I still have to look out for a suitable potential maker of my mask!

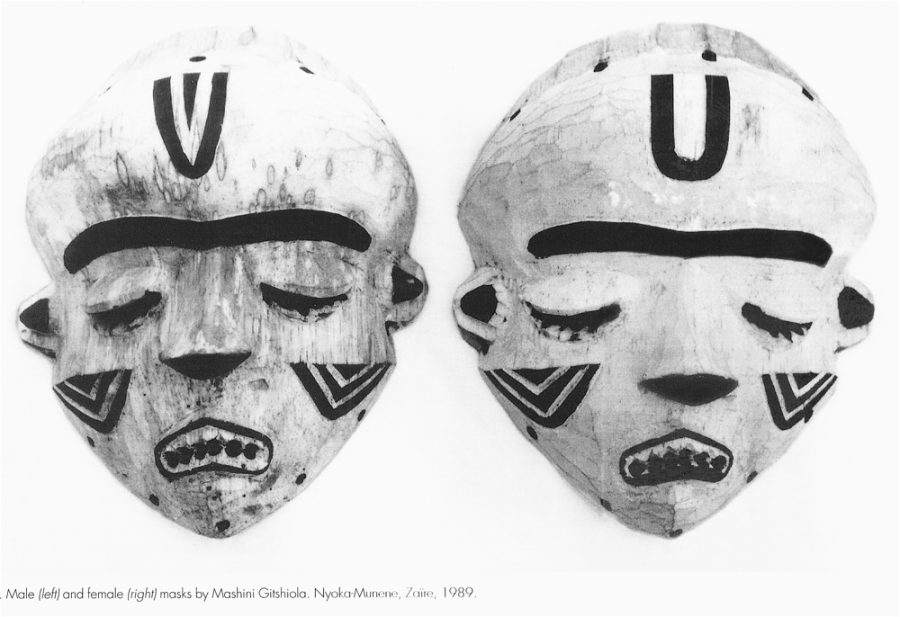

Zoé Strother about masculine masks of Mashini Gitshiola:

Mashini is at the height of his powers and confident of his ability to distinguish between the feminine and every degree of masculine. One finds the gender unmistakable even in unfinished masks. He adjusts the forms of his cicatrices to heighten the effects of his sculptural volumes. The blunted triangular arrows call attention to the thrust of the forehead (fig.40) Even the eyehole, a subtle point to read for Westerners, is fraught with symbolism for the Pende, as it conveys the famous hooded gaze (zanze) of female masks. Mashini’s style is quite distinctive in its angularity and clear separation of parts. He always uses cicatrices, whose shapes vary, on the cheeks to underscore the beauty of) prominent cheekbones. The male face is narrower and hence appears longer and leaner. (Chapter 6, pp. 123/124 – summarized)

One female and three male prototypes by Mashini Gitshiola in direct comparison

In Fig. 40, a masculine prototype (‚basic male, as not yet named’) is shown next to a female. They differ in the frontal view only in nuances. Both have a forehead with a striped U-pattern to the edge, broad raised eyebrows with blunt ends, boat-shaped scars with triangles on the cheeks, angled mouth with drilled teeth and – I can not help it – in both cases the expression of a ’stupid Clown‘. The horizontal edges on the cheeks look rather strange.

These correspondences support de Sousberghe’s overall judgment and seem to qualify the meaning of ‚physiognomic grammar‘ in these case. But let us look at two more ’male’ mask faces by Mashini Gitshiola!

The next, shown in Fig. 39., looks in the profile view really like mine.

A third male mask by Mashini Gitshiola: The beautiful young man MATALA (Index p.344)

In Mashini’s mask MATALA all of the masculine features above are exaggerated (126,Fig. 41). In Mashini’s interpretation, the forehead bulges out even more, and the eyes become much larger in overall size an opening. His eyebrow is more refined as befits his beauty, and yet pointed at the ends (unlike fig. 39, 40). The plane under the cheekbones is quite flat and the chin distinctly pointed. The mouth extends a bit farther, especially the upper lip. As in Mashini’s theory, the upper lip rises in the middle and forms an acute angle – an echo of the lower lip – in order to convey the potential for aggression.

Perhaps, the point (pièce de résistance) in MATALA is his nose. Mashini takes always pride in its soaring distinction. It is clearly turned-up, with a sunken bridge, and exposes enormous nostrils. One thinks of the Western physiognomists writing in praise of a lange nose. (124, summarized) Mashini claimed once that such a nose demonstrates the cleverness of its subject. (126)

“There is a clear correspondence in the mind of the audience between the vigor of the dance and the vigor of the features of the face. The proud flip of MATALA’s nose may also be deemed appropriate for a dancer who whirls, ducks and spins. Whatever the argument, European or Pende, it is hard to ignore a sublimated phallic imaginary.“ (126)

Where do new masks come from?“

Stroth quotes Tzvetan Todorov with the question: „Where do genres come from?“ And his answer: „Quite simply from other genres. A new genre is always the transformation of an earlier one, or of several: by inversion, by displacement, by combination. „(224: Genres in Discourse 1990,15) Strother recalls corresponding transitional forms from the years before 1920 toward a more naturalistic representation of the eye by carving the upper and lower eyelids and opened the eye hole. (224 and Fig. Hilton-Simpson 1911, link). „The easiest way to transform standard forms is by changing the sex.“ (225) „Those performers seeking to distinguish themselves, the mask of the young woman proved to be one of the most potent models.“ (224) That promoted the trend towards naturalistic design of face, costume and dance, and was a sign of the growing emphasis on entertainment in the masquerades. as well. (224)

„MATALA beautifies every dance floor!“ (Mashini Gitshiola, p.70)

Gipangu Zangela from Mukedi was said to have been inventor of MATALA, a renowned dancer of the Mapumbulu generation, who was initiated in 1916-19 (Link). In transport contracts – a Frondienst – for the mission of Mennonites he had come far around. He brought back a „Luba“ dance that imitated the helicopter-like flight of weaver birds, and introduced it successfully (65-67). While he himself performed the dance for decades unchanged, his imitators gave the dance a proper identity through changes in hairstyle, costume, gestures, and foot rattles. But distinctive movements too secured MATALA a permanent niche in the local masquerades. „Probably because of his association with a new and ’modern’ dance and because of the use of the thumb-piano beloved by young men, the popular mind quickly interpreted MATALA as a young man.“ (67) Trendy young ladies already existed with GAMBANDA and GABUGU.

.

But that’s not all: Zoé Strother saw MATALA already as a young dandy with elegant shirts or vests, fine socks, watches, everything that makes a fashion-conscious young man stand out, also long hair and poses that allow him to admire his elegant profile. (67)

MATALA demands a persevering and flexible dancer (68). The well-known dancer Khoshi Mahumbu (fig. 22, p.69) felt this in his fifties when his wife told him: „You are too heavy“. At the dance festival in Gungu, a MATALA dancer was critizised “for showing his age.“ „He betrayed the illusion of youth and strength through his lack of flexibility.“ (69)

The ’business policies’ of village mask carvers 1989 (pp. 87-90)

Among the seven professional carvers in the village, Zangela and Mashini 1989 fell between the extremes in terms of the number of masks produced: they averaged perhaps five to eight masks a week. They had large local clienteles, although they were obligedto rely on the Kinshasa tradefor every day expenses. Mashini filled orders of the mid-men with unusual punctuality and carved in a style that appealed to younger enterpreneurs. The price of the mask was based on how much work was involved, for example for eye and mouth openings which risk splitting the wood and required more time and skill. The raffia hairstyles were the most time consuming part. (89)

Mijiba was the only carver who lived on masks made in foreign styles. He owned Cornet’s book Art de l ‚Afrique au pays du fleuve Zaire (Bruxelles 1972): He copied masks of the Luba, Songye and others, frequently making subtle mistakes since he never had seen the pieces. One collegue who had built his reputation on Pende masks made foreign works as well, perhaps as artistic challenge. (69)

By the way, those foreign works were already used in Pende mask performances by dancers in search of a ‚ gimmick‘. (89)

In that context Strother rises the question of ’authentic’ and ’fake’. She mentions two typical situations:

“A dancer in a hurry may purchase head-pieces intended for the foreign trade.“

“A middle-man with a back-log of commissions may arrive at the right moment and can confiscate a head-piece intended for a dancer“. (89)

“A cherished ten year old piece will look brand new.“ Dancers or middle-men will ‚age‘ these treasured pieces only when they are released for the international market. (89)

Could my specimen also be a MATALA made by Mashini Gitshiola?

The angularity of the face, the grotesque forehead, wide eyebrows, the retracted eye area, disproportionately large stressed eyes, the clearly turned-up nose with plenty of room for nostrils …. the upturned aggressive mouth sits directly on the pointed chin.

In my view that are striking arguments;

And what if it would be true ? Then the piece would be just one of those five to eight copies Gitshiola used to produce weekly, and anyway one lacking the ’time consuming’ raffia hairstyle, but at least with all the required openings. Formally and in its expression it is strong anyway.

My conclusion is : A masterwork for The Louvre, au minimum !

SHORT EMAIL DEBATE (12th to14th January 2019)

Dear Detlev,

Thank you for the fascinating article. I am intrigued by your idea that the mask was carved by Mashini Gitshiola. He was the one sculptor from the 1980s who was still alive and working in 2006-2007, when I visited. I can’t resist sending you a few photos that a colleague took of our visit.

Dear Zoé,

I am very happy about the photos and the kind permission by Marvin Goertz to publish them here! Mashini is a really likeable person and sort of ’neighbour‘! Marvin’s snapshots really capture the atmoshere of joy and understanding.

A Delicate Criterion!

Dear Detlev,

Interestingly, Pende sculptors say like Morelli that the best way to distinguish the hands of artists is by regarding their ears! From what I could tell, the tragus on the ears on your mask are smaller and sharper. One might think that a style could evolve. I hope you will be able to see enough about the ears in the photos from Mashini’s late style.

Dear Zoé,

Best view i have ever seen !

Sorry to say but Mashini died april 2017. He was a good friend of mine.