Die Macht einer ‘Polio’-Puppe (Pende)“ Revised and translated : July 26th 2024

Our first encounter May 6th, 2017

At the flea-market I come across a strong and bizarre figure of the classic African cripple, not even on one of the folding tables, but kneeling on a simple blanket on the ground, solid upright in a realistic position, frighteningly naturalistic, which brings to mind my own experiences, and at the same time a good classic Pende carving.

The materials are: wood, fabric stretched over wood, cane/reeds, resin, and fresh banana straw; 42 cm high ( 17 inch; with straw 45cm), weight 2 kg.

At first I try to put the seller K.K. off by pointing him to museums, but I am not yet sure whether he would not find another ‘curiosity’ lover at the market. He does not find one that day. I contact him a week later at his home and, with my heart pounding, I buy it.

I can’t ‚live with‘ this figure like I do with others – I would have to ‚change my life‘ – but I can put it online and advertise for ‚real‘ help. And I want to know more about it. At some point it will have to go to an institution.

The Aesthetic Aspect

The artist ingeniously designed the crucial angles of the hands and feet. I am looking again and again in disbelief at the bamboo tubes connected by cloth and resin. The angles – including those of the rigidly spread fingers and toes – are ‚real‘.

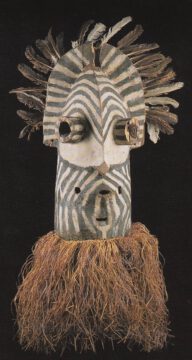

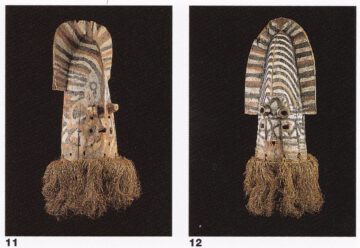

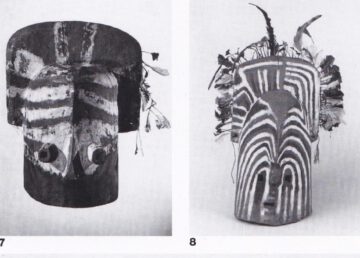

I don’t even wonder about the upper body/torse, an angular wooden body made plausible by a shirt. And a face that simultaneously shows the „realistic“ expression of repeated physical exertion and the typical facial traditions of northern Pende masks.

As William Rubin wrote in ‚Primitivism…‘ (MOMA, N.Y. 1984):

„The artist only had to transfer the traditional stylization of his people to physical phenomena. Picasso’s distortions, on the other hand, were an invented projection…„

(Munich 1984, p. 274)

What is more ‚violent‘? For me, it is still reality. Aesthetics is, after all, an illusion.

The aesthetic quality of the carved face particularly moves me. The power of tradition is not diluted by coquetry. One should focus on the Polio puppet as intensely as on the context, but this would need experienced researchers perhaps in the future.

A Mobilizing Power

A few days later. Her strength is evident in my donation to the Unicef program, which is atypical for me. Admittedly, I had already seen the moving documentary „Benda Bilili“. and copied the subtitles of two lyrics by the beggar band from Kinshasa. ( LINK to en.Wikipedia)

Staff Benda Bilili. Papa Ricky is the father of the street kids….

I once slept on cardboard boxes Bingo

Soon I’ll be able to afford a mattress

That can happen to you too

To you, him, anyone

A man is never finished

Good luck comes unexpectedly

It’s never too late in life

One day we’ll make it I once slept on cardboard boxes….

No one has the right to judge others

Life comes and goes

No one has the right to judge a street child

No one chooses his life

The children from the Mandela Roundabout are big stars

They sleep on cardboard boxes

The disabled people from Plateform are big stars

They sleep on cardboard boxes We have cardboard boxes!

You have no right to laugh at me ….

Papa Ricky was filmed at the Centre for the Care of Physically Handicapped People in Kinshasa. During a recording session at the zoological garden of Kinshasa following YOUTUBE was recorded :

I was born as a strong man but polio crippled me

Look at me today, I’m screwed onto my tricycle

I’ve become the man with the canes

The hell with those crutches!

Parents, please go to the vaccination centre

Get your babies vaccinated against polio

Please save them from that curse

My parents had the good idea to register me at school

Look at me now: I’m a well-educated person

Which enables me to work and support my family

Parents, please don’t neglect your children (don’t throw anyone on the side)

The one who is disabled is not different from the others (why should he?)

Treat all your children without discrimination

Who among them will help you when you’re in need? God only knows who.

Screenshot 024-07-27 2024 : youtube.de CrammedDisks plays the song „Polio“ by Staff Benda Bilili with English subtitles: Staff Benda Bilili – (LINK)

“Vaccination information from door to door” by UNICEF

“ Obstacles to vaccination campaigns -Just one look at the map makes it clear to me: In a country that is six to seven times larger than Germany, many regions are hardly accessible. (…) Transporting any medication is complex and expensive. This is especially true for the oral polio vaccine, which is very sensitive to heat. Due to the remoteness of many villages, it is also difficult to inform all residents about the medical services available and to encourage them to get vaccinated. There is often no electricity, no television or radio. In addition, one must not forget that Congolese parents are also worried about harmful side effects of vaccinations.

However, resistance to vaccination in some regions is based primarily on cultural and religious reservations. Marco Kiabuta, a religious leader in a village in northern Katanga, preaches: „We don’t need vaccinations because we only have one doctor and that is God.“

To increase the willingness to be vaccinated, UNICEF and its partners are placing more emphasis on education. To this end, UNICEF is working with aid organizations, local initiatives and communities and offering training courses. Traditional and religious leaders such as village chiefs and priests are also being persuaded to work with them. Because they have easier access to the population due to their recognition as authorities. Their words are believed. Personal communication has proven to be the most effective. Trained community workers, health and vaccination assistants go from door to door, from family to family as so-called „mobilizers“ and explain the dangers of and protection against polio….”

The presentation sounds conventional in the original. Political and social problems in particular are only hinted at, in the manner of Aid organizations.

Into the world behind one-dimensional presentation of Sickness

The question of the possible use of the puppet does not leave me alone. The seller waves it off. The figure has passed through too many hands. I speculate randomly: When health workers go through the villages, as UNICEF reports, such a figure could have supported them. But could the terrifying doll really be suitable for that situation?

The ‘traditional’ African horizon of interpretation

I read in Frank Herreman: To Cure and Protect, Museum of African Art 1999, p.19:

“Many objects which show disease are used to caution against antisocial behavior. This is especially true of masks which are danced in performances teaching or reminding the members of the community about adult rules and responsibilities. Images of deformation are also considered representations of the negative forces ort malvolent spirits that are activated when moral values are transgressed….“

So the victims themselves are responsible for the serious illness that struck them? Is this perhaps a motive for elders to resist vaccinations, to give a big threat out of hand?

2024 : I would like to refer you to the blog „An expressive Mbangu Mask“ of the Pende (LINK)

Anecdotes

Telephone conversation with Prof. Joseph Franz Thiel (1932-2024), former missionary, academic and director of the Weltkulturenmuseum in Frankfurt. (Aug. 18th 2017)

I describe the puppet.

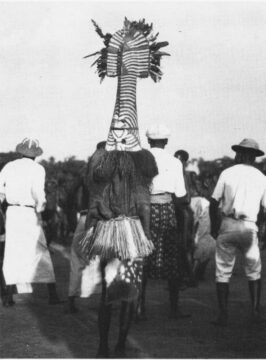

Thiel: Yes, Pende, that is typical of them. They show the illnesses that others hide because they represent everyday life in a very concrete way. He starts talking about highly distorted illness masks. They dance them.

Me: but what about puppets?

He doesn’t know exactly: Dance or set up at certain times. He hasn’t heard of them being used by healers. He starts talking about literature, remembers an illustration, but can’t find it.

I say: the figure is solid, I estimate it to be half a century old.

Thiel: it could also be a whole century.

And he tells an anecdote: The last time he was in the villages of ‚his‘ Yanzi’, in 1971, neighbors of the Pende in Bandundu Province, he once sat with some elders, when a young, formerly beautiful woman crawled in. Of course, according to the people, she was bewitched and possessed by evil spirits. She had also been impregnated by a married man, he learned on that occasion. Thiel was at least surprised: That’s not possible, she can’t look after the little one like that, the grandmother will have to do that! The old men’s answer: You can’t leave a fertile field fallow.

„The fertile womb“ among the Pende (Sept. 9th)

I come across the „fertile field“ argument again without this metaphor – in Zoé Strother’s „Inventing Masks“ (University of Chicago Press 1998).

She reports an incident from 1963-65, when, in response to a narrowly limited rebellion by Pende against the new regime in Kinshasa, soldiers plundered and set fire to numerous villages in the Pende region as a reprisal.

“Families fled into the forest. The mother of an acquaintance became separated from her family and was fleeing alone down a road with her young son strapped to her back. All of a sudden, she spied a soldier coming in her direction down the road. Fearing robbery or rape, she threw down her young son and fled off into the bush. Later, she was able to collect the boy and rejoin her family. The young woman no doubt reasoned instantly (and correctly) that the child was in little danger from the soldier. Nevertheless, there were witnesses. Some time later, when order was restored, the woman was called before the chief and elders to account for her actions. With a self-possession unusual in Pende women, who are not accustomed to speaking in public, she stood. She is reported to have answered with disdain: „Would you have me, a fertile woman, risk my life to defend a boy? … A boy who will never add a person to this lineage? (…) The woman’s bald statement scandalized the crowd. Her behaviour did not conform to the idealized love that a mother that a mother owe a child in Pende society. All the same, after hemming an hawing the chief could only dismiss her, saying weakly: Well, next time, try to take him with you.” (pp.3-4)

The Pende are organized on the basis of matrilineal rights, and women sometimes blame their husbands if they only give birth to sons and not daughters. (p.4)

The fertility of women means, socially speaking, the obligation to give birth. This is of course closely linked to the duties of a ‚mother‘, familiar from the Bakongo people in Kejsa Ekholm Friedman’s essay „Catastrophe and Creation“ (harwood academic publishers 1991, ISBN 3-7186-5186-6; chapter ‚A Modern Clan Society‘, section: „Duties of a woman“ ).

“They use us like brood hens…”die tageszeitung, Berlin 4.4.2012

A reportage from Northeast Congo, Dungu district, in the rebel territory of Joseph Kony and his „LRA“.

First of all, this photo catches my eye. His family has left behind the paralyzed boy in the village. Like the Pende boy, he was later found unharmed – The staged press photo seems to prove that. What thoughts and emotions was the picture to trigger in the European viewer?

A young mother interviewed by reporter Simone Schlindwein in a UNHCR camp 2012 fared worse. She and hundreds of classmates had been kidnapped from their school 2008 and enslaved. “They tied us together like slaves with a rope and dragged us into the bush.” The sexually mature girls were given to the fighters as wives. She was assigned to a Ugandan fighter and gave birth to her son ten months later. “They use us like brood hens to give birth to their children.”

J.F.Thiel : “The Song of Antoinette Bukibi” in the Chapter „LITERATURE WITHOUT WRITING“

I finally got around to reading Josef Franz Thiel’s book, a unique book: „Jahre im Kongo“, Lembeck Verlag Frankfurt/Main 2001. It can be a foil that links all possible aspects of the society and thinking of the peoples of Central Africa. (2024 See Blog Links, in German)

- It is an introduction to ethnological thinking,

- A field study and research report (between 1961 and 1971),

- An activity report and analysis of the institutional framework of Catholic ’pagan mission’ in the 20th century (See Blog : „Josef Franz Thiel. Anekdoten beim Spaziergang an der Nidda erzählt“ (LINK)

- An autobiography of a totally unpretentious and, for the most part, entertaining story-teller.

The Song of Antoinette Bukibi

On the pages 100 to 104, we meet the crippled woman Antoinette Bukibi again, performing her song in a traditional style in a convivial village setting. As a singer, she amazes the audience.

Thiel: „One evening I drove with my secretary Tanzey Bruno to his home village of Shie, which is only about seven kilometers from Manzasay. We had announced ourselves to some of the old people the day before. I took kola nuts, palm wine and cigarettes with me. If a younger person gives an old person these gifts and he accepts them, he is also obliged to give honest answers to his questions. Kola nuts and palm wine in particular are not just material gifts, but also express recognition of the older person’s higher status. They are therefore also popular offerings to the ancestors.

We sat down in a circle and began our conversation. Bruno managed the tape recorder so that I could be completely free for the conversation. At first we were almost only a group of men, but later more and more women and children joined us.

A young, crippled woman came crawling along on her hands and knees. She was holding a little block of wood in her hands and had a cloth wrapped around her abdomen. Her legs were completely bent. From crawling on the ground her knees resembled the hooves of an animal. But she had a beautiful face and her eyes looked intelligent and sharp-sighted. She sat down on the ground in front of me and asked me if she could recite something to me. I held out the microphone to her and she began to sing in a beautiful and firm voice. She sang in Kiyansi and only occasionally mixed in Kikongo expressions.

1.

Mother, the man of books has come this night. I had already seen him yesterday. E ngo ya!

2.

When a child cries, you calm it down with lullabies. The fire also attacks the wood of the Mpier tree. Engo ya!

3.

The marten steals chickens, but Nzambi [God] steals people. E ngo ya!

4

Last night I had an obscene dream, I didn’t dare tell my brothers-in-law. E ngo ya!

5

I saw a strange thing: a rooster had horns on its calves. E ngo ya!

6

The sorcerer is God’s little brother. When the white man passes by, you see him. When God passes by, will you see him too? E ngo ya!

As is customary, I put a banknote in the singer’s mouth and gave her my full palm wine glass so that she could drink and I lit her a cigarette. She crouched at my chair for a while, smoking the cigarette in a womanly manner, i.e. with the fire in her mouth, then she slid out into the night on all fours and disappeared.

Her performance had impressed me, and everyone else too; there was a long silence. They had obviously not believed she had the courage to sing such a song. I had heard some of the content; the language was OK, but I had not understood the meaning.

When I had transcribed the wording together with Bruno over the next few days, I sat down with Bruno to discuss the background of the woman’s situation and her song.

The singer’s name is Antoinette Bukibi. She was a pretty young girl when she became ill. When she had been crippled for several years, a married man from the village impregnated her. She gave birth to a healthy girl who was about two years old in 1967. I made a disapproving remark about a man impregnating a woman who can only move with difficulty. But Bruno had a different opinion: „It is good that she gave birth, so she has not lived in vain and her name will not die.“ „But who will take care of the child? The man is married and has other children,“ I objected. „The Zum will take care of the child, as he is already doing for Antoinette. You yourself heard the old Sandukumpampa say last night: ‚A fertile field – you don’t let it lie fallow.'“ (101)

J.F.Thiel transcribes, translates and interprets the text over the next few days with the help of his local assistant. Not only does the Bayansi poetics and their transformation of everyday realities come to light, but Antoinette Bukibi is also presented to us as a suffering and proud person, similar to Papa Ricky.

About the song’s content:

1. Antoinette incorporates my arrival in the village into her song. I was actually in Shie the day before with Bruno to register with the old people Kiana and Sandukum- mpampa for the evening.

2. Antoinette compares herself to a small child who is soothed with songs when it cries. The people in the village also talk to her in this way: her illness is a fate that nothing can be done about. She has to endure it. Even the large, shade-giving tree of the savannah Mpier (also called Lupier) is caught in the fire during fire hunting in the dry season and turns black; however, it does not burn. She should also be happy that she did not die. As soon as the rainy season begins, the tree sprouts again. She too has given birth to a daughter and, like Lupier, has brought forth new life.

3. Here Antoinette shows the typically traditional attitude of the Bayansi towards God: she compares him to a marten that catches chickens. The Bayansi often address God as chief. In the past they called God Nziampwu muil minawa in Kiyansi; today they like to say Mfumu Nzambi in Kikongo. Mfumu and Muil means chief. Perhaps they call God chief because, like him, he is uncontrollable and always gets his way. They have a fatalistic attitude towards God. One proverb says: „We are God’s bananas – he cuts some when they are green and others when they are ripe.“ And another says: „God has set a trap – the animals he catches with it are us humans.“ In this third verse, Antoinette seems to blame God for her situation. She will argue differently in verse 6.

4. In the fourth stanza, Antoinette compares her illness to a dream that is so obscene that she dares not tell her brothers-in-law about it. She uses the word buko (in Kikongo Bukilo) for brothers-in-law. This term refers to all in-laws. But it is certainly not the Parents in-law that are meant, because there is a strict taboo against them. However, there are joking relationships with the husband’s brothers and vice versa with the wife’s sisters (called „joking relationships“ in ethnology), as the brothers and sisters are potential marriage partners should the husband or wife die. In ethnology, this form of marriage is referred to as Levirate or Sororate. Joking relationships can also include intimacy and a lewd tone is usually permitted, especially if one party is still unmarried. If the husband goes away for a long time, he entrusts his wife to his younger brother. If a wife becomes ill or has a child, her younger sister or a cousin (i.e. a classificatory sister) often comes into the house to run the household. She is often also sexually available to the man, with his wife’s consent, because the wife is taboo to the man for almost two years after the birth of a child. Only when the father can send the child to fetch a light to light his cigarette or pipe – the child is then about two years old – is his head shaved for the first time and marital relations with the woman can be restarted.

Antoinette wants to say that her illness is as unspeakable as an obscene, even pomographic dream that she does not even dare to tell her brother-in-law, although she can have erotic relations with him. – In other words: she does not want to tell anyone about the suffering that being crippled brings her, because she is ashamed of it.

5. This verse is basically an embellishing reinforcement of the previous one. Antoinette now compares her illness to a strange, incomprehensible, even never seen event: a rooster never has horns, and if it does, then never on its calves. Her illness is incomprehensible to her. Her life has been destroyed by it.

6. The sixth verse expresses the typical traditional way of thinking: the illness is caused by a sorcerer (Muloki, in Kiyansi Ngaa mu’m). The sorcerer is called „God’s little brother“ because, like him, he causes people to die. But then Antoinette highlights the difference between him and God: the white man is a powerful man; he has everything, can do everything – according to the villagers – and yet you see him when he comes to the village or when he passes by. Perhaps she is also alluding to the previous story, when she saw me but I didn’t see her. Then comes her decisive statement: you see everyone when they pass by, even the white man. But when God passes by, you don’t see him. But if you see the white man, you will definitely see the sorcerer one day. In other words: he will be exposed and punished. She hopes that justice will prevail in the end.

On other Girls’ Songs

Not all of the Bayansi songs are as cryptic and difficult to understand as Antoinette Bukibi’s. The girls‘ songs often take aim at the social misdeeds of the people in the village. When they sing their songs in the villages in the evening, the people affected are pilloried. But the villagers agree with this approach, even if they are occasionally exposed in this way. I received always the answer that the songs help to maintain order. However, it is almost always minor offenses that are socially ostracized in this way. For example, a girl was caught stealing fish at the market. The incident will, however, reduce her bride price. Or a father washes his little daughter in the stream without considering that this could be interpreted as incest (kud’).

On June 12, 1967, I recorded numerous songs by the girls from Shie with Bruno. The most difficult thing about the songs is not understanding them linguistically, but knowing all the details of the surroundings and all the allusions. I have sometimes made recordings and had them copied word for word on the spot. When I then translated them in Europe, I realized that although I understood everything linguistically, I lacked the necessary background knowledge to understand their meaning. Some gaps could be filled in by letter, but it also happened that I took tapes back to Africa, played them to people and asked them what they were trying to suggest. It would be ideal if everything could be worked out on site. But there are often other obstacles to this. (104)

On Childish Witchcraft in Kinshasa – My Postscriptum 26. July 2024

In some aspects Antoinette resembles Papa Ricky. And in my eyes her poetry and courage rises above the singing of the street singer in Kinshasa.

But Ricky’s simple language is also full of allusions, the meaning of which is easily hidden from us Europeans and Americans. The Belgian ethnologist Filip de Boeck, who specializes in West African megacities, has been describing the changes in Kinshasa for decades – in English. I have translated a few of his articles into German and collected them in a blog chapter (LINK)

Filip de Boeck wrote 2004 in his essay ‚The Second World – Children and Witchcraft in the Democratic Republic of Congo‚ – that ‚Child witches‘ have become so numerous in the streets of Kinshasa since the 1980s that even international press agencies and our television stations report on them from time to time. Children between the ages of four and eighteen are accused of witchcraft by family members, they are said to have caused mishaps and accidents, but also illness or death. Numerous local Pentecostal churches pay much attention to the figure of Satan, demons and the battle between good and evil. During holy masses and communal prayers, the children are urged to make public confessions in which they are asked to reveal their true nature as witches and name the number of their victims.

Seldom they succeed to reconcile the ‚witches‘ with their environment, as it should traditionally work.

In general, de Boeck warns against applying Western concepts of childhood and child protection to this situation without thinking. Children in Africa are not always just victims, but are also perceived as active agents, for example in public testimony against adults who allegedly introduced them to witchcraft, as feared child soldiers (who were drafted into Kinshasa with Kabila in 1997), as financially independent young people and finally in the mythology of the big city as „sugar dolls“ who are dangerous for men and are often associated with the mami-wata mermaid, which best expresses and raises awareness of the links between sexuality, gender, age, death, access to modern material goods and the „second world“. (36-37). (…) He draws our attention to the fact that, particularly in the predominantly ‘informal’ economy, young people have better chances than adults because they are often more ‘street smart’. (p.47, note 20 to 40 in „Africa Screams“ , the catalogue of the Weltkulturenmuseum, Frankfurt 2004, ed. Tobias Wendt, pp.30-47)

In an extensive and passionate essay on the history of Kinshasa (LINK), de Boeck sums up in 2005:

• Kinshasa is getting younger and younger – youth gangs and youth culture

• The rural periphery has regained importance. While the city has become village-like in some respects, the bush is where dollars are generated and villages are transformed into booming diamond settlements.

À Suivre! Avanti!