Updates and additions January 8, 2022

1. Work report 2. Case study (Kraków, Poland)

One trendy keyword you may expect in the headline is missing: „stolen“. And another keyword: „Saved“.The only prominent German case that comes into question concerns the original boat stem from the possession of the Lock Priso, saved from destruction by the representative of the Deutsches Reich in December 1884 during an act of war. He confiscated this informally as the property of the rebel as a welcome piece of booty for the newly founded Völkerkundemuseum in Munich. (Post 1 in French. And in the recent phase of ‚rediscovery‘, a century later, a descendant of Lock Priso made a claim for restitution in his struggle for a political position in Duala and pursued it for twenty years publicly and legally. The museum fought back with scientific studies, the state of Bavaria with administrative law. – I know that every word about this case can become a booby-trap rhetorically. So much for this case and back to the models. (Post 2/3 >“Bibliographical Notes“)

1 ETHNOGRAPHICA AND CURIOSA BUSINESS

At the turn of the last century, boat models were a popular commodity of the type “Curiosa”. Numerous business people, colonialists, and agents acquired such models of various qualities in Duala to sell them to the newly established ethnological museums in their respective homeland or to wholesalers such as H.F.G Umlauff.

A year ago I did not know how systematically and internationally organized the business with Ethnologica and Curiosa was carried out. The acquisition of model boats by the Fields Museum in Chicago in 1925 sheds some light on the system. (Post 6)

At the same time, it must be clear that Duala boat models played a rather modest role as ‚bycatch‘. this resulted in negligent documentation – they were often not even mentioned.

„AUTHENTICITY“ IN „CONTACT ZONES“?

The derogatory assessment by the prevailing doctrine of ethnology played an important role, which I briefly discussed in the “Rafai blog” – in the post (1/5 German!). In 1912, for example, Prof. Thilenius, then director of the Hamburg Museum of Ethnology, was an exception among ethnographers by keeping an eye out for objects from the “contact zones” (Grotaers) while the vast majority were obsessed with “uncontaminated art” of clearly defined “tribes”.

Is the past tense in „were obsessed“ correct? The competition still exists:

The increase in price of ‚ritual objects‘ still works today, credible „ritual use“ is still a strong criterion for “authenticity”, even if it cannot be used consistently. The recent complaint of an expert for the Benue area between Nigeria and Cameroon proves it:

„…. Sorry I don’t think its helpful to be definite when in my opinion this is impossible. What we know is that a) there are strong regional similarities and b) there was trade between groups so really you cant know specifically where an object was used from its appearance or even from where it was carved. Worse than that I have Mambila evidence that the names/uses of different masquerades was determined by the ‚medicine‘ of the group not by physical attributes of the carving they owned at any one time – and conversely that all carvings owned by one of those groups would properly be called by the name of the medicine irrespective of what it looked like. But all of these scruples are irrelevant if the objects were ‚made for trade‘ as almost all objects in the market are. You need really strong provenance to establish that a specific object was actually collected in the field and used in ritual. And to complicate matters still further ‚made for trade‘ objects have been and are used in ritual so are „authentic“ whatever that word means!

In short you are opening a ‚can of worms‘ if you know that idiom! (Original mail 22.2.21)

The Cameroon Delta has been a classic “contact zone” for two hundred years. Atlantic trade flourished since the 18th century and since 1846 the ‚civilizing‘ work of English mission stations was successful. The ritual objects of the Duala disappeared over time or changed until the traditional forms were only made for the market. In the course of the 19th century, boat races evidently became increasingly politicized sporting events, naturally also employing magical powers, which should not, however, be overemphasized. Anyway, the ‚traditional‘ aesthetic culture of the Duala had been shaped by manifold influences, from subjugated neighbors and trading partners on the Cameroon coasts and the Niger Delta (Post 4 „Virtual trip to the Niger Delta„), as the studies by Rosalinde Wilcox show.

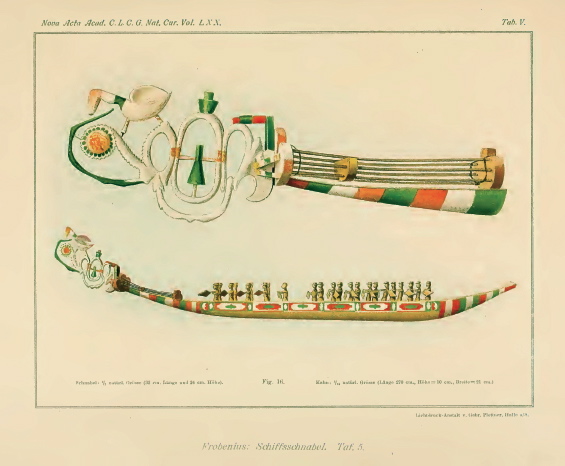

Young Leo Frobenius, at that time still a parlor scholar, undertook in his essay in 1897 to reveal traces of a tradition in the „Ship’s beaks“ of the Duala boats, which were connected with the history of mankind. (I’ll come back to this in a later post (10?).

As far as the later obviously modernized and commercialized boat models are concerned, the idea of arbitrariness is obvious. But it still has to be proven in detail!

DEPOTS AND LOSSES

The generally meager index cards published by museums speak for themselves.

The literature on Douala boat races and bowsprits has been precious and scattered, even more the literature on the corresponding boat models.

Under the German colonial occupation, the regattas are said to have been regulated („Kaisersgeburtstag“), thinned out and finally extinct. The ‚Ngondo‘ festival on the Wuri River, which was revived after 1945, was later banned for ten years by the dictator Ahidjo and reintroduced – initially – during the unsuitable rainy season.

As far as I know, Else Leuzinger (Die Kunst von Schwarz-Afrika 1972, cat. O8 Coll. P.Harter) and Kecskési 1982 started with a black and white image of boat beaks (tange) in catalogs. At that time, „Cameroon“ meant „Grassland“ and if „Duala“ was announced, traditional flat attachment masks were shown, ironically invented by the Ijo and also found among the Ijebu on the Niger and Kalabari on the Cross River (again: Post 4)

In America, too, only in the 1980s they were taken from the depot, restored and exhibited, as by the Fields Museum (Post 7a) .

The aftermath of the war severely impaired and damaged museum depots, not only in Germany. Much was lost, some decorative parts survived. At my request, generally unknown, inconspicuous and perhaps never exhibited boat models appeared from various depots.

2 A CASE STUDY (KRAKÓW)

Author: Jacek Kukuczka in an email dated February 19, 2021

Guten Tag! I am a curator in the section of non-European cultures our museum. I confirm, that we house collections from Africa including Cameroon (in polish Kamerun). As a matter of fact, this collection is the biggest and the oldest among historical african collections in polish museums. It is known as collection of Stefan Szolc-Rogoziński (1861-1896). The collection was gathered in West Africa (among cultures from Canary Island and Sierra Leone to Cameroon) beetwen 1882-1885. The second half of this collection comes from the years 1886-90, from Equatorial Guinea.

One of the biggest and also the most important(?) exibit in this collection seems to be „model of Duala war canoe/pirogue” (no. 18726/MEK). It is 241 cm long, 22 cm wide (max) and about 10 cm deep. The model has 14 rowers (former was more but some are missing) with oars. All of them in characteristic French(?) caps. We dont’n know neither exactly origin place nor the circumstances of acquiring the object. Probably, it could be somewhere around Limbe or Victoria, as well as in delta of Wuri River (called by Rogoziński as Cameroon River)

Originally, the model had a decorated beak (tange) but unfortunately, this beak didn’t survive to our time (or, it disappeared during or after WW II). We have only the ilustration from Leo Frobenius’ book and some archive photos. Unfortunatelly, we dont’n know the sizes and more details about beak. Shortly speaking, we only know what we see on archive photos. Acording to those photos and proportion we guess, that tange could be about 50 cm long.

Some archive photos were made before 1939, when our museum was situated on Wawel’s Hill, in complex of Royal Castle in Kraków (after II WW museum is situated in former City Hall in Kazimierz District). I can also add, that we have two original Duala oars (one of them, see attached photo) with characteristic paitings – the same as found on the side of the boat model.

As a context to the model you should know basic information about collector. His life was short and tragic. But he had a dream and he fulfilled it (at least, partly). So, shortly speaking, Stefan Szolc-Rogoziński, was a man, who had bad luck in Africa. He appeared in Cameroon in „bad place and in the bad time”. As a Polish, who was a citizen of Russian Empire (becouse, as you surely know, Poland in XIX century didn’t exist and was devided beetwen Russia, Germany (Prussia) and Austria), he tried to explore Africa, especially Cameroon for „future Poland”. But, in this time two empires (British and German) divided this part of Africa and Rogoziński was exactly in between. He had to lose and he lost. He had to „escape” in 1885, because after 1884 there was not space for „independent polish explorer/explorers”. But he didn’t give up and he returned to Africa again, already in 1886. This time on Fernando Po (Bioko) in Spanish Guinea (Guinea Equatoriale), where he tried to do a business as a planter. He spent in Africa the next four years, partly with his wife.

Stefan Szolc-Rogoziński made several geographical discoveries, but he did not entered history, but rather was erased from it by German explorers and colonizers. Even in the publication of Leo Frobenius (1897) you don’t find any information about him or about who, when and how delivered this model to Krakow!

But Szolc-Rogoziński and his two friends (Leopold Janikowski and Klemens Tomczek, who died in Africa in 1884) did great job as „explolers without support and goverment power” (in contrast to German and British). They spent almost 3 years on small island Mondoleh and they organized several inland expeditions, including Cameroon, Gabon and even Congo. In this way, Rogoziński gathered more 300 objects and – fortunately – transported them to… Kraków. Why Kraków then in Austria? Because it was quasi-free town and because it was a city that allowed Poles to shape and develop culture and science (Kraków was semi-independent town with national freedoms).

As we know today, it was a good choice, because Krakow survived World War I and II. By the way, Janikowski had less fortune – his Cameroon and Gabon collection was completely burned down along with the entire Ethnographic Museum in Warsaw as a result of the German bombing of the capital of Poland in the first days of September 1939.

That is a short history and wider context to our Duala war canoe.

Best regards, Jacek Kukuczka curator, non-European collections, The Seweryn Udziela Ethnographic Museum in Kraków (LINK to website)

Updated January 8, 2022 : On the role of Rogozinski in Cameroon

Last September I suspected: Szolc-Rogoziński certainly came to Cameroon at the wrong time to do research there. Did he have connections to London, the recently outmaneuvered competitor of the German Reich, as his photo suggests?

Two articles in Wikipedia gives a clear answer :

„Szolc-Rogoziński undertook several research trips to the interior of Cameroon. By means of so-called protection treaties he tried to enlarge the region around today’s Limbe, which was claimed by Great Britain, but in 1887 passed into German ownership. (…) „. (Translation of de.wikipedia (LINK)).

And Original unabridged of en.wikipedia:

After a career in the Imperial Russian Navy, he organised an expedition to Africa with Klemens Tomczek and Leopold Janikowski. His expedition in Cameroon lasted from 1882 to 1884. Rogoziński was commissioned by the British government to act as an agent in the African interior. He had accepted in part because relations between him and local Baptist missionaries had broken down over his decision to sell alcohol to the locals.[2] The missionaries had given him the nickname ‚Rogue Gin and Whiskey‘. The German press was extremely angry at a Russian citizen being employed by the British to frustrate their imperial ambitions in Cameroon, and Rogoziński’s hatred of Germany was well known. Chancellor Otto von Bismarck even made specific reference to the explorer in the Reichstag while complaining about Anglo-German relations. German anger and diplomatic pressure caused by the lead up to the Berlin Conference in 1885, led to the British dismissing Rogoziński from their service. They refused to use the many treaties he had negotiated to press claims in what had by now become recognised as German Kamerun. After his return, in 1895, he joined the Royal Geographical Society. In 1892-1893 he organised an expedition to Egypt. He founded the National Ethnographic Museum in Warsaw (Państwowe Muzeum Etnograficzne w Warszawie) and donated his collection of items and artefacts to the museum. He died in 1896 in a traffic accident in Paris. (last edited on 26 August 2021, at 20:33 (UTC).“

Literature used by en.wikipedia:

- Będkowski, Mateusz (12 December 2012). „Wyprawa Stefana Szolc-Rogozińskiego do Kamerunu a polskie marzenia o koloniach“. Histmag.org. Retrieved 24 July 2015.

- Rudin, Harry. (1938). Germans in the Cameroons: 1884-1914: A Case Study in Modern Imperialism. Yale University Press. New Haven. p.46-47

A scientific conference in the Warsaw Ethnological Museum, an accompanying event for the exhibition „Wiwat Polonia! Traces of Poland in Africa. Past and present.“ 2014 honored him as the „enfant terrible of the colonial times in Africa“. (LINK polish)

By the way, I would be interested in his hatred of Germany. Did it have something to do with the extreme border location of Kalisz and the painful division of Poland?

Brief Note on Swedish Citizens in Cameroon

It would be interesting to follow more biographies of people from different European countries who were looking for their chance in the supposed ‚Eldorado‘ of Africa, not to forget the many missionaries who spent their lives!

The Swedish „Världskultur Museerna“ in Stockholm (LINK to their website, English!) tells us of a Peter Möller in the context of a Duala object: „… In the years 1883-86 M. worked, among other things, as a ‚factory‘ manager in the Congo. He described his experiences in a book and reported also on his expedition in what is now Angola and Namibia 1895-96 in ‚Travel in Africa through Angola, Ovambo and Damaraland‘ (1899). In the years 1899 and 1900 Möller toured South and Central America. He founded a coffee plantation in British East Africa in 1911. „(re-translated)

We learn about the collector of an interesting model canoe (inventory number: 1919.05.0082; collected 1883-86): „Georg WilhelmWaldau (Valdau), born October 17, 1862 in Västerfernebo, Västmanlands, died December 13, 1942 in Santa Cruz in Tenerife. Together with Knut Knutson, Georg Waldau founded a trading company in Cameroon at the end of the 19th century. He lived on Tenerife from 1909. He married Ida Maria Lórange Waldau. (1880-) on August 17, 1909. Son of Major Johan Oscar Waldau ( 1822-1878) and Maria Sofia Sandels (1839-1874) …. „(re-translated)

To my question „When exactly did he found the trading house at the end of the 19th century„? Magnus Johannson from „Världskultur Museerna“ promptly points out an interesting publication to me: „He and Knutson came to Cameroon 1883. You can read more about their time in ‚Swedish Ventures in Cameroon, 1833-1923: Trade and Travel, People and Politics – Knut Knutson – Google Books‘ LINK). The website offers a generous „book preview“.

Another interesting story would be that of Fritz G. Theorin – a Swedish employee in an English factory in Gabon. He also brought a boat model from Duala to Stockholm.

P.S. Fortunately, Swedish museums were not affected like others in the twentieth century.