All images can be enlarged twice by clicking on them!

Chapter 1 : AN INSPIRING CORRESPONDENCE

DUNCAN (31. Dezember 2020)

I greatly admired the French version of your blog on Duala boat models. Like you, I try to learn as much as I can about objects in my collection.

DUNCAN (10. Januar 2021)

Take a closer look at my 125 cm long model of a Douala canoe:

c Collection Duncan 2020

- The figurehead, consisting of a snake coiling around a loop enclosing three ovals linked by a horizontal perforated bar, as if the ovals were wheels driven by an axis or chain,

- A man sitting on either side of a large decorated splash board,

- Paddler in front of a central canopy. He wears a shirt with a red belt, collar and stripes across his chest like the men on the splashboard,

- A central canopy covering an imposing man in white, whose skullcap is the same color as the bulbous ones on other figures – again white – but bigger,

- And three figures behind the canopy – two paddlers and a man facing backwards on the stern, who probably held a steering oar. All three of them have the same kind of uniforms as the men in the bow, except that the red elements are white.

- Finally, the black hull and canopy are decorated with red and white geometric patterns whose slants and verticals reflect the posture of the figures. The round ovals and dots in the figurehead are also carried through the model, since related motifs occur on the canopy and stern.

DETLEV (10 January)

You have a very interesting Duala boat model, if it’s “Duala” at all. First, there are some features that link it to known canoes and boat models from Duala:

- The connection of a canoe manned by rowers with an oversized bow ornament („figurehead“).

- The figuratively decorated cross board („splash board“) through which the prow ornament is fastened to the canoe is attached, the classic snake, and the three connected ovals are all typical of the „Duala“.

- The colored, geometric decorations on the boat wall and the standardized two-dimensional and perforated arms of the rowers are also seen on several Duala boat models.

Some important aspects point in another direction, what I’d like to illustrate by examining my second boat model, from the neighboring delta area of the Niger. “It’s Yoruba”, the seller explained to me. At 72 cm long and 27 cm high, it is a lot more compact than yours. Here are a few noteworthy similarites:

- the compact and high body (tapered downwards) with a canopy supported by two side walls

- loosely distributed geometric drawings that are only painted rather than carved

- the braided technical connections

- the small number of relatively large figures with large pear-shaped heads which remind me of ‚Yoruba‘ heads and faces, and especially of the big bean eyes of the Ibedji

DUNCAN (11. Januar)

Congratulations on your deductions concerning a Yoruba connection!I noticed the resemblance of the heads to those of Yoruba statues, and especially on some Ibeji, and initially looked for comparable boat models in books like “Yoruba: Sculpture of West Africa” .When I couldn’t find any, I turned my attention to models purportedly made in the region of Douala by the Duala ethnic group, and noted that they often had similar splashboards, iconographic elements in their figureheads (e.g. snakes looping and zigzagging around wheel-like forms), and conventions such as round flat hands with circular holes for paddles (which suggested that several of the models were made in the same workshop). The combination of the Yoruba-looking heads and iconographic and technical conventions made me believe that my sculpture might have been created in a transition zone, where cultural and aesthetic influences mixed. Your arrival at the same conclusion makes me think the hypothesis might be true.

I must delay writing more now because of a sudden onslaught of deadlines. I look forward to continuing our detective work.

DETLEV (21 February)

Dear Duncan, are you past your various obligations? With your ‚hybrid‘ boat model you opened open my eyes to Cameroon’s relations to the Northwest, to the Niger Delta and beyond. My “main suspects” for our two newly introduced boat models are now called “Ijebu Yoruba”.

Chapter 2: HOW ROSALINDE WILCOX INSPIRED A CLOSER LOOK AT THE NIGER DELTA

Wilcox‘ seminal art-historical study „Commercial Transactions and Cultural Interactions from the Delta to Douala and Beyond“ („African Arts“ t.35,1; 2002) is full of details, impulses, questions and allusions. Although it does not deal directly with canoe building and boat models, but rather with canoe oars, horizontal masks and masquerades, it proved to be especially useful to to our analysis.

In the first blog I saw the Duala people as a mediator between the rivers of the hinterland of the Wuri Delta and the Atlantic beyond the island of Fernando Po. Prof. Ronald Daus reported on the strong immigration into the city of Douala since 1884, during the colonial era, but emphasized the internal migration of the “Bamiléké”, a broad ethnic term in this context (LINK to (1) in german) Rosalinde Wilcox provided a fresh perspective concerning the Duala and the multicultural port city associated with them. When you say “Duala” you have to be clear, since that term sometimes conflates with the name of the place (Douala), the resident population (the Douala) and ther specific cultural tradition of the Duala people. as a consequence, I accept Wilcox’s suggestion for differentiated spellings.

In this and the following chapter, we leave the Douala region to follow coastal and fluvial exchange routes northwest along the Atlantic coast to the Cross River (Kalabari), to the great Niger Delta (Ijo, Ijaw, Ibibio, Ijebu-Yoruba etc.) and even beyond. Speaking of which, Kru seamen from Liberia and the black carpenters and joiners from the Gold Coast (now: Ghana) exemplify how migrant workers and traders spread along the entire Atlantic coast.

Rosalinde Wilcox characterizes the region as follows:

“Inhabitants of Africa’s eastern Guinea coast live in similar ecological environments and have similar political and religious beliefs, particularly a belief in water spirit cults. Their colonial history repeated itself along the coast. People in river and coastal communities where canoes dominated, particularly in Nigeria, Cameroon and Liberia, shared historical and economic experiences. They used their surroundings for fishing and salt production, and traded with inland groups. The companies on the coast traded with Europeans in the 16th to 19th centuries and used and expanded their pre-European contacts and trading networks in the hinterland far beyond modern political borders. „(42 M)

None of the three successive European colonial powers could stop the exchange of goods, people and ideas at their new political borders, she points out, because “trade is insensitive to modern borders”. In addition, Cameroon’s southwestern province was part of British Nigeria for forty years (1919-1961). Unfortunately, the multiethnic character of the region compounded by language dispute between Francophone and Anglophone ’speakers‘ – more exactly constitutional promesses and political reality – has created a simmering source of political conflict (LINK to ACAPS), and other problems typical of post-colonial dictatorships in Africa.

Wilcox also notes that communities of Ijo, Igbo and Efik, which are usually associated by outsiders with Nigeria, have long lived on the coast between Douala and the actual Cameroonian border with Nigeria. As a consequence, the formal conventions of Duala, Ijo, Ibibio and Efik art blend into one another in ways that have contributed to an ‚international‘ art style on the coast. – When we will return to look at the Cameroonian coast, Rosalinde Wilcox‘ insights will prove useful once again..

Chapter 3: CANOES AND PEOPLE IN THE NIGER DELTA

But for the moment, let us turn to the cultic and festive use of canoes in the Niger Delta, as illustrated by museum catalogs and art-ethnographic articles in publications as „African Arts“. Some of the phenomena observed are typical of both the coastal regions and river deltas.

I have to limit myself to a few aspects, especially of the boat models I come across .

A lively and colorful catalog from Los Angeles (UCLA) will accompany us into the meanderings of the rivers and the connections between art and the environment of the Niger Delta: „Ways of the Rivers – Art and Environment of the Niger Delta“ (2002).

Coast and Delta specialists – the Ijo

In the 4th chapter, the co-editor Martha D. Anderson presents the Ijo as prototypical river delta inhabitants:

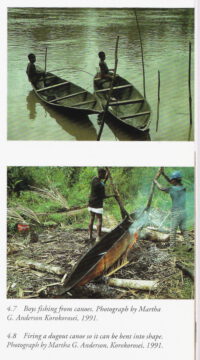

In regions of the Delta where roads are inexistent and even footpaths limited to seasonal use, canoes still provide the primary, and sometimes the only, means of transportation and intervillage communication. … Canoes seem so fundamental to their riverain lifestyle that some assume the art of canoe-making came from heaven with them. (Alagoa 1970, 323) Nearly every traditional occupation practised in the freshwater region – including fishing, farming, distilling gin, and trading – necessitates water travel. Canoes also serve other mundane functions that are harder to classify, satisfy social and receational needs, and figure prominently in performances of various types. Canoe effigies even play a role in shrines and rituals.“

„Learning to paddle seems to be largely a practical matter without religious or mythic significance, but the process plays a critical role in shaping the way people view the environment. As children, the Ijo begin to differenciate between two zones, the rivers and forests, and to associate different levels of danger with each.“ (136)

They learn to row in a playful way, they swim early, and bright children can row alone at the age of seven or eight to the neighboring village, perhaps an hour away. (137) The Ijo also use the river as a performance space, using canoes and other watercraft as moving stages. Spectacular war canoes are the highlight of some festivals and are a reminder of the warlike past of the Ijos. Raffia fronds and other “bulletproof” charms are attached to it. (140)

p.140 Fig. 4.13 – with a horizontal sawfish mask

„Since water spirits, like humans, navigate the waterways by boat, mask dancers embodying water spirits use the immanent drama of the boat trip by arriving from the water.“

„Most Ijos now consider themselves Christians, but the idea that the Deltas’s rivers and creeks represent a different world continues to captivate them. Some tell stories about encounters with aquatic spirits or describe marvelous water towns they have visited in person or in dreams. (…) People often describe them as beautiful, light-skinned beings with long, flowing hair, but they can also materialize asanimals, composite creatures, and objects that turn up in the water.“ (148)

We recognize the Jengu (LINK) of the Cameroon coast, as well as the water spirits known under the name Mamiwata, which are worshipped all along the Atlantic coast up to the Congo Current ( I recommend in English: Henry J.Drewal: “MamiWata – Arts for Water Spirits in Africa and Diasporas “, UCLA LA 2008).

Respect for the water world – the Ijebu Yoruba

Another author, Roger de la Burde, tells us of the ambivalent relationship of the Ijebu Yoruba to water and its spirits and their cooperation with the Ijaw/Ijo river people and fishermen in the neighborhood.

As soon as Duncan and I deducted that our boat models showed a „Yoruba“ influence, I found an early edition of “African Arts” (autumn 1973) with a report on the Ekine cult of the Ijebu Yoruba on the western edge of the Niger Delta, which they adopted from the neighboring Ijaw.

Not all the delta’s inhabitants were as connected to the water world as strongly as the Ijo/Ijaw. The Ijebu Yoruba adoption of the cult is an example both of the spread of respected cults along with their objects and conventions among neighboring ethnic groups, and of the fact, that Ijo rites provided a readymade template for expressing strong ties to the water world.

„For the Ijebu Yorubas who live adjacent to the mid-coast section of Nigeria, one of the powerful forces of nature is water or its personification , the impredictable Water Spirits. In contrast to northern and middle Yorubaland which is predominantly mildly rolling territory, the southern Ijebu area is basicly flat. There, major rivers like the Shasha and Owena are joined by hundreds of tributaries. Although, these creeks have a low water level or are completely dry in the dry season, they swell to enormous proportions durig the rainy season, flooding the surrounding plains while rushing to the sea.“ (28)

Yet these people, like most Yorubas, preferred to retain a strong union with land, marked by their worshipof the Ogboni edan, „the Earth Principles to whom they delegated kingmaking and governemental functions “ L.E. Roache). Water Spirits were of lesser importance and were worshipped in relatively few Ijebu villages and towns. They were regarded as mischievous creatures who emerged only to do their harmful deeds and then quickly disappeared into their dark and secret hiding places. The Ijebus tended to avoid the rivers and creeks which they believed to be the homes of these spirits…. G.Afolabi Ojo attributes this to the inferiority of the coastal Yoruba groups to the River and Delta people of southern Nigeria, both in fishing techniques and in the catch itself. They left fishing actvities to immigrant Ijaws, Urhobos, and Jekris. (28)

„In spite of their aversion to water, it was the close proximity to the sea and navigable rivers which dictated the activities of the Ijebus, establishing solidly in trade. Their position of importance in commerce was reinforced by the fact that in the past, both the kingdom of Oyo and the town of Ibadan had to use the Ijebu routes as an access to the sea. This brought relative wealth to Ijebuland and also gun powder, thereby guaranteeing a degree of military independence. Because of their affluence, the southern Ijebus did not need to develop great efficiency in farming. (…) One of the groups with which the Ijebus had contact was the Kalabari Ijaw, (…) renowned for their expertise in fishing and canoe building, Some old Ijebus will even acknowledge that the Ijaws were very helpful to them as traders because of their intimate knowledge of the rivers.“ (28 )

These Ijaws developed the most extensive water spirit cult, Ekine, which was mainly characterized by its entertaining masquerades. The Ijebu introduced the Ekine cult without assigning it a political role – for example in the judiciary. During the season of the water spirit festival, both Ijaw and Yoruba-style masks were used during the dances or to lead the water spirits Igodo, Agira and Oni to their simple shrines, which had been built on the banks of the local streams and rivers before the festival. During the festival, when they were particularly unpredictable, people wanted to be safe from them as long as possible. When the rituals werde over and the dangerous period had passed, they were returned of the homes of the Ekine elite – of “those who have nimble legs and arms and who, during dances have Water Spirits in them.” There they were kept behind the rafters of the roofs and frequently smoked for protection from insects, to be restored prior to the next ceremonial use. Since the 1920s, valuable pieces were painted with expensive Western oil paints for their protection, which the Ijebu had acquired through their extensive trading activities. (32)

„Thus by establishing contact with the Water Spirits, appeasing them with offerings, occasionally even outwitting them, the Ijebu Ekine cult helps the community to cope with the hazards of water. In the past, members were even able to catch these elusive Spirits and immortalize them in the form of headdresses. The evidence indicates that, because of their geographic location, the Ijebu Ekine apparently were able to distill some ancient elements of the Yoruba, Benin, and Kalaba Ijaw cultures which they transformed to suit their spiritual needs when creating these unique headdresses and festivals“. (32)

Canoes and boat models in cult and festival (and for export)

Let’s look at a few more boat-shaped objects. Some details give clues to their use. But their forms are basically as diverse as their real life models. Why shouldn’t they have been universally applicable and only given appropriately adapted names?

1 – 2 Ancient Egypt

The oldest examples, which might be somewhat comparable, come from pre-dynastic Egypt. One – approx. from 3400 B.C – in „Dawn of Egyptian Art„, p.65, cat.66: “Boat model with painted oars“, Ashmolean Museum Oxford. A second “Barque funéraire en terre” (clay) in Cahiers d’Art, Christian Zervos, Paris 22e année 1947, p.42, Musée de Berlin) is 57 cm long and has a roof.

3 „Canoe to heaven“ (Urhobo Art, p.134f. cat. 75)

A more recent example, an expansive crown mask that represents an occupied canoe, Perkins Foss illustrates in the catalog of the Museum for African Art, N.Y.. He notes that every family group has such a ‚canoe‘ which was set up with other things in front of their property as a temporary shrine during funerals. A photo, taken in 1971, which is hard to read because of its smallness, shows a grieving family behind a miniature boat and sacrificial vessels.

Between the lands of the living and of the dead lies water. The deceased „travels on the water“ and the symbolic means of transport is thought to make the journey easier for the deceased. The text does not say anything about how such models or canoe headdresses were danced.

There are five people in the boat (cat. 75) and a dog on the bow. The two boatmen stand in front and behind, carrying small oars in their hands. All have tall heads and wear traditional or European hats. Four men frame the dead man, two of them may be musicians. The dead man faces backwards. He is discreetly guarded but also protected, because, as the artist Bruce Onobrakpeya said, when interpreting the Urhobo cosmology in the catalog, the passage into the underworld is long and dangerous. Since nobody knows where the dead are, nobody should give instructions carelessly. Following the trackless path requires extra sense to accomplish.

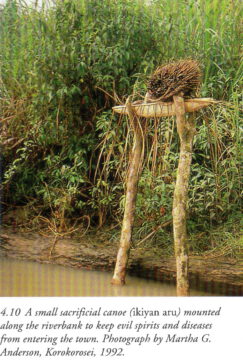

„On the last day of water-spirit festival, called edjenekpo, when the spirits travel back to their ethereal abode, the spirit canoe is again brought out, this time to assist the spirit forces in their trip home. This return trip is critical: while the spirits are invited to attend festivities held in their honor, it is crucial that they leave this world in an orderly way and return home.“ (135)

‚Hades‘ and ‚Heaven‘: The name of the boat, oko-re-Erivwin, is usually translated as “canoe-to-heaven”, but in the next text Erivwin means “the underworld of those who have left the land of the living” (135). A lively discussion under Urhobo, which took place in Niagara Falls, Ontario in 2000 follows in the catalog. It was about the preservation of traditions under the conditions of modernity and Christianization. (137-138))

4

The catalog “Ways of the River” also shows such an Urhobo mask attachment (fig. 4.2, 60cm, FMCH X86.2504) and comments: “Numerous delta crown masks suggest canoe shapes or contain correspondingly reduced canoes. The neighboring Itsekiri make a version so large that it takes two dancers to carry it. Masks depicting modern means of transport – bicycles, helicopters, and airplanes – have also become popular, and some of the Kalabari Ijo depict ocean liners.“ (133)

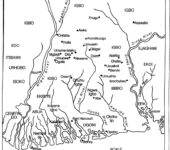

An article entitled “Spatial Continuities – Masks and Cultural interactions between the Delta and Southeastern Nigeria” by Eli Bento in African Arts (spring 2002) deals with the ways that modern art-history has viewed works produced by the confusing accumulation of little-known (in the West) ethnicities, which comprise the delta’s population. His map names at least some of the ethnic groups of the delta to imagine such overlapping borrowings and influences. Without the colonial and post-colonial history of the area, the main part of the study is frankly more for specialists.

5 Small sacrificional canoe for water spirits along a river bank (Ijo)

6 Manned festival boat of the Urhobo

“Urhobo Art” shows the photo of a roofed and festively decorated boat with (allegedly) thirty rowers who accompany the appearance of a water spirit. The Umalokun ritual was developed by the neighboring Itsekiri and introduced to the Urhobo in the 1940s. (Photo Ughelli 1966).

7 The boat of domestic harmony (Ogoni)

Caption: “This sculpture probably served as a masquerade headdress. The „house“, which enhances the sense of domestic harmony, may have been built in to protect the occupants or cargo of the canoe from sun or rain on a long journey. Like most Delta women, the „woman“ sits at the stern and acts as her husband’s chauffeur. „ (136)

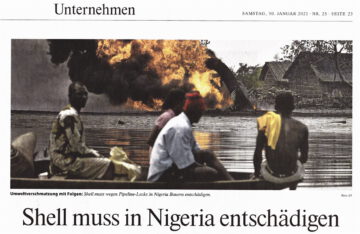

„Shell has to compensate in Nigeria“ ….a couple of villages after years of litigation! Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung (FAZ) 30.1.2021

The high artistic standing of the Ogoni is one aspect, but we should not forget how sixty years of catastrophic oil production by Shell-Nigeria has lead to their increasingly precarious situation.

I recommend „Genocide in Nigeria – The Ogoni-Tragedy“ (London 1992) by Ken Saro-Wiwa, the intellectual and activist for the Ogoni and Delta cause, who was executed after a show trial in 1995 (LINK on DW-Akademie 2015, in german)

8 MOCKERY AND ENTERTAINMENT

The celebrations and their masquerades also include mutual teasing and entertaining jokes, often for educational purposes. The following anecdote also shows how the competition between water and bush spirits, at least among the Ijo, allows such features.

Caption to Fig. 4.14 (142) in “Ways of the Rivers”: “A girl who pretends to paddle on a bench during an Inamu dance, which originates from bush spirits” Korokorosei 1991)

Martha G. Anderson writes: „The irony inherent in the idea of canoeing on dry land obviously appeals to the Ijo. In a dance – Inamu – introduced by bush spirits and copied by numerous villages in the region, young girls make paddling motions with appropriately shaped dance wands, then transform a bench into a canoe (fig.4.14). They paddle it, dance on it, drag it around the arena, and eventually tumble onto the ground when they capsise it. Masquerades often include similar parodies. Some reenact fishing expeditions. A performance formerly staged at Korokorosei portrays the aftermath of a domestic quarrel. The wife prepares to leave for her father’s house by loading her canoe one article at a time, while onlookers beg her to stay. At first their entreaties make her more annoyed, but they finally persuade her to remain when she returns home to collect a forgotten machete.“ (140-141)

9 Court Arts and Crafts (Benin) – Representative Collector’s Item

„Bronze boat with Oba and Nobles. Probably end of 19th Century, beginning of 20th Century“ L 40,5 cm, B. 10,5 cm H 17,5 cm Estimate 15.000 DM

10 “White Men”

Thomas Ona (Odulate): „Boat with figures“ (44,5 cm)

In the same essay („Ways of the Rivers“ A8 p. 64) Martha G. Anderson also notes that a sculptor named Ona, who made canoe models, „produced charming portraits of colonial officials for a largely Western clientele. He worked in a typically Yoruba style but carved each element seperately, then combned them into scenes like this one – an imperious British district officer being paddled about the creeks in a canoe. Although Europeans sometimes suspected they were being caricatured, Ona claimed to be more interested in portraying emblems of rank and authority, when interviewed by William Bascom, that her was simply representing the world as he saw it.“ And Frank Willett adds: „When Ona was interviewed by William Bascom, he stated that he simply represented the world as he saw it“. ()

In the same essay („Ways of the Rivers“ A8 p. 64) Martha G. Anderson also notes that a sculptor named Ona, who made canoe models, „produced charming portraits of colonial officials for a largely Western clientele. He worked in a typically Yoruba style but carved each element seperately, then combned them into scenes like this one – an imperious British district officer being paddled about the creeks in a canoe. Although Europeans sometimes suspected they were being caricatured, Ona claimed to be more interested in portraying emblems of rank and authority, when interviewed by William Bascom, that her was simply representing the world as he saw it.“ And Frank Willett adds: „When Ona was interviewed by William Bascom, he stated that he simply represented the world as he saw it“. ()

11 A Current Offer (‘IJO’)

In May 2020, the Cameroonian art dealer Salif M. offered me such boat models of the “Ijo”, about 1 m long, 70 cm high at the umbrella, colorful and with a hybrid boat body that is reminescent of both water spirits and fish.

Bibliography

(in the order of appearance) (* only images)

Rosalinde G. Wilcox : „Commercial Transactions and Cultural Interactions from the Delta to Douala and Beyond“ in „African Arts“ vol. 35,1; spring 2002, p. 42-54, 93).

Martha G.Anderson and Philip M. Peek, Editors :„Ways of the Rivers – Art and Environment of the Niger Delta“ , UCLA Fowler Museum L.A.2002

Henry J.Drewal : “MamiWata – Arts for Water Spirits in Africa and Its Diasporas”, Fowler Museum at UCLA, L.A. 2008

Roger de la Burde : „The Ijebu-Ekine Cult“ in „African Arts“ vol 7,1 automn 1973, pp.28-32

Diana Craig Patch : „Dawn of Egyptian Art“, MET N.Y. 2012 *

Christian Zervos : „Sculptures et textes poétiques de l’Égypte“, Cahiers d’Art Paris 22e année 1947, p.42, Abb. Musée de Berlin

Perkins Foss : “Where Gods and Mortals Meet – Continuity and Renewal in Urhobo Art“, Museum for African Art N.Y. 2004

Eli Bento : “Spatial Continuities – Masks and Cultural interactions between the Delta and Southeastern Nigeria”, African Arts, spring 2002, p.26-41,91

Frank Willett : „African Art„, Thames and Hudson, London 1971,1991, p.143

*

Many thanks to Duncan for checking the American version. Remaining bugs and flaws are still mine. Detlev