Field Museum of Natural History — Jan Kleyman — Baron v.d. Heydt — J.F.G.Umlauff — World market for ethnographics

Foreword

You know the story of my canoe model from blog two (LINK: „My Special Duala War Canoe Model“). I still have a snapshot of the handover to offer.

On the trail of the twenty-seven boats Leo Frobenius documented in 1897, my inquiries all over Europe and the USA had a good response and at first I did not know how to handle more than thirty documented models.

In the meantime I have even come across three more boat models with exact the decorative bow (tange) of my boat model. Two landed in American museums, one at a modern private collector like me. I intended to discuss them alltogether, but the first ‚object biography‘ arrives elsewhere than intended. It turns into a milieu description and expands from the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago via a transatlantic deal to major players in the German Reich: J.F.G. Umlauff in Hamburg and Baron von der Heydt. And it doesn’t really focus on the object in question. – Comparative considerations will have to wait.

The Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago (LINK)

The Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago was inspired by World’s Columbian Exposition from 1892-93, a big crowd puller on the shore of Michigan Lake celebrating the “discovery of America” in 1492. The Museum was named in honor of the first major donor, the department store ’king’ Marshall Field. The first (only unofficial) curator for anthropology was Franz Boas, the one who professionalized America’s anthropology. An interesting German-American biography by-the-way ! (LINK en.wiki) The museum is holding important collections.

At the end of February, the museum curator Christopher Philipp pointed out an imposing model of a boat well over two meters long (access card A no. 1608). He answered my questions, gave valuable advice, and provided a few insightful documents.

The large model boat came into the possession of the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago as part of a collection of almost two thousand objects of Cameroon art. The curator has sent me detailed documents about this acquisition. Of course, this transaction alone would be an inexhaustible field of research and has so far been unsatisfactorily documented.

The purchase in the summer of 1925 proceeds quickly.

Gallery owner Jan Kleykamp of New York informs Stanley Field in a letter dated June 16, 1925 that he has given orders to ship the Camerun Collection to him, all charges prepaid. He reminds Field that he receives the collection on approval in his Institute under the condition that the Institute would pay for the return in case he might not purchase the Collection.

Kleykamp says that he had to buy the collection, with his partner in Holland, along with a very nice collection of Chinese and Japanese paintings. And since he specializes in early Chinese art, he is interested in turning over the collection as soon as possible and makes the Institute the low figure of $ 30,000,00 (Thirty thousand dollars) for nearly 2000 pieces which barely cover his purchase price and different expenses he had on the Collection hitherto. He offers payment by installments and asks for a decision as soon as possible, since other institutes may be interested, even if he has not yet shown any photos.

The Curator of Anthropology Dr. B. Laufer writes to Kleykamp on June 23:

I note that in the two albums illustrating your Camerun collectionthere a 8 plates in which photographs of certain specimens have been cut out which appear in the original albums of Umlauff. There are 14 missing specimens altogether, as follows (….) It seems that these are just the best specimens picked out and retained by the original owner. Whether this was done by Umlauff or Baron von der Heyt or someone else I do not know of course. I wish you would find out and insist on having these 14 objects restored to you, as it seems a pity that the collection should thus be spoiled.

I wish to call your attention to another matter. In the preface to his album Umlauff states that that the original list of the collection which is very detailed and 600 photographs taken by the collector, Schroeder, in Africa would be given gratuitously to the purchaser of the collection. You should see to it that you receive both the list and the photographs, as it would be invaluable to me in cataloguing and labeling the collection. Yours very sincerely (Signed) B. Laufer

On July 14th, J.C.F. Umlauff, the son of the owner Heinrich Umlauff from Hamburg writes:

Sehr geehrter Herr Doctor ! Im Auftrage des Herrn von der Heydt, Zandvoort, sandte ich Ihnen heute per D.Deutschland eine Kiste enthaltend 540 photographische Platten. Liste über die einzelnen Aufnahmen liegt bei. Mit vorzüglicher Hochachtung

He is sending a box with 540 photographic plates. These are sent at the request of Baron v. Heydt, Zandvoort. A list is with them signed J.G.F.Umlauff

On July 27th, the curator B. Laufer sends a two-pages recommendation to the executive director of the Field Museum D.C. Davies.

He praises the cultural area of Cameroon, which represents the highest development of Negro art. In this respect Cameroon culture shows many affinities with the ancient art of Benin, which is well represented in the museum, and that of the Sudan. (p.1)

The bronze castings of this group rival those of Benin, and their wood carvings are probably the best made in Africa. Many of these wood-carvings represent portions of chieftains houses like door and window frames …. The specimens are all well defined according to locality and tribes, and there is no doubt that they were collected with intelligence and good judgment. It is a very fine collection of great scientific interest and artistic value. (p.2) Unlike the more haphazard acquisitions, it gives an accurate and complete picture of a well defined cultural area, and it vividly illustrates the Negro’s accomplishments in industrial art. There is no such collection from Africa in this country, and there is presumably no museum outside of Berlin which has a similar collection. (p.1)

On August 7, 1925, the acquisition of the approx. 1950 objects is confirmed. The purchase price is $ 27,000; the photos have not yet arrived at the museum and will be requested again.

……. disregarded

In the abundance of things mentioned listed, surprisingly, the two-meter ninety-long boat-model of the Duala – today an attraction – is missing. At that time it was probably not “authentic” enough, regardless of its formal qualities, as a Cameroonian ‚export product‘ without good reputation.

The boat is not mentioned on the access card No. 1608 – Date: Aug.7 1925, signed B. Laufer – not even in a summary of the objects list. Musical instruments, tobacco pipes, baskets…? – Sure! The Boat? – No! For years it is just a number between Catalog Numbers 174051 and 175823. Its almost empty property card dates from the 1950s.

Then things are brightening up:

In 1968 No.175469 is extensively restored for four weeks, according to the conservator’s report. This is done at the instigation of Leon Siroto, 1965-70 Assistant Curator African ethnology (Fieldiana anthropology 2003, p.260)

The bow in particular needs it:

all surface very dirty … stern end of canoe broken and badly repaired (glue, nails, screwed together, over painted) …wood damaged by wood beetle…. Missing elements have to be replaced, extraneous substances removed, missing area reconstructed ….

I now understand the striking long-distance effect of the long hull and its figures and can explain the less „fresh“ condition of the bow decorations. I am not really convinced that they originally belong together as they are as usual only linked by a device.

The dugout was pictured by Leon Siroto in „Njom – The Magical Bridge of the Beti and Bulu“ (African Arts vo.10 no.2 Jan. 1977) .

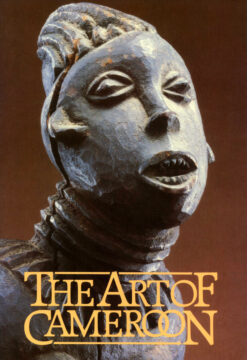

And at the exhibition “The Art of Cameroon” 1984 in Washington D.C., New Orleans, Houston, Chicago, and New York, the boat does not make it onto the title, but to page three of the catalog!

The emoting words „Benin Bronzen“ and „Berlin“

With “Berlin” and “Benin” in connection with “portions of chieftains houses” from the kingdoms of the Cameroon grasslands, questions arise about the acquisition activities of the companies Lauffer, Hagenbeck and others in the colonial era .

Previous business relationships with Hagenbeck and Umlauff

Field museum curator Philipp mentions the second boat model (catalog number 28504), already described by Rosalinde Wilcox (2002, African Arts t.35, p.49). According to his information it had been part of the Hagenbeck collection, which came to the museum immediately after the closure of the world exhibition in 1893. (Mail on February 27, 21) And in his mail of March 1, 21 he adds: The Museum does have extensive holdings of both Hagenbeck material (originating from the 1893 World’s Fair – like the other canoe model) and extensive dealings with J.F.G. Umlauff not linked with Kleykamp. He also notes the direct line from Dr. Laufer and Umlauff.

„Jan Kleyman Asian Collection“ and Dr. Berthold Laufer

The chinese and Japanese paintings acquired by Jan Kleyman from Umlauff and v.d. Heydt go to the Art Institute of Chicago (AIC) in a representative exhibition building (LINK). The Kleyman Collection are on display for a month from December 15, 1925, introduced by Berthold Laufer (1874-1934). (LINK)

Philipp (Mail 1.3.21): Berthold Laufer was a long term curator for the Field Museum spending nearly his entire career here – He was specialized in Asian material and that is likely the connection for his dealings with the Kleykamp collection of paintings that could be at the AIC. He is responsible for the extensive Chinese holdings that we care for in Chicago.

Baron Eduard von der Heydt (1882-1964)

Excerpts from the de.wikipedia article (as of Dec. 24, 2020, accessed July 13, 2021 (LINK). The article en.wikipedia „Eduard von der Heydt“ is a stub, sorry.(LINK)

Before 1914 he was a banker in New York and London, her became diplomat, art collector and patron, he bought Monte Verità near Ascona in the Swiss canton of Ticino in 1926 and made it an exclusive social meeting place. He began collecting Asian and African art on a large scale in the twenties, based on the idea of ARS UNA : Art is not nationally or regionally restricted, but rather forms a fundamentally unified human work. He built up one of the world’s largest private collections of Chinese and Indian art, lending numerous works to museums. As a monarchist and national conservative, he became a member of the NSDAP in 1933, acquired Swiss citizenship in 1937, and served as a banker for Germany in Switzerland during World War II. The US government confiscated his American bank balances and assets in the United States in 1948. 1946 von der Heydt donated his East Asian art collection to the city of Zurich as the nucleus for the Rietberg Museum. Since 2008, the Rietberg Museum has checked the provenance of the 1,600 objects in the von der Heydt collection in order to track down Nazi-looted art. As a result of this review, compensation was paid to the heirs in 2010 for four works of art.

By the way, we already met the Baron Heydt in former blog posts as a customer of Charles Ratton (Link) and as Mentor of Werner Muensterberger (Link).

The company J.F.G. Umlauff in Hamburg

We’ll understand the details of the deal with the Gallery Jan Kleyman and the Field Museum in America now better. Their business partner in Hamburg held one of the central positions in world trade with ethnographics. That was true at least until 1914.

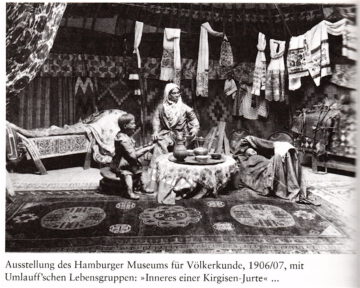

A careful study of the literature and files by Hilke Thode-Aurora under the title „Die Familie Umlauff und ihre Unternehmen – Ethnographica-Händler in Hamburg“ (Mitteilungen des Museums für Völkerkunde Hamburg, neuer Folgeband 22, 1992, 143-158 ) sheds light on the complicated family and business connections and explains the business policy. I quote from it, partly in summary. To illustrate Umlauff’s activities, I quote four reproductions from Britta Lange’s study: „Echt. Unecht. Lebensecht. Menschenbilder im Umlauf“ (Real, Fake, Lifelike. Images of people in circulation) ,Kadmos Verlag, Berlin 2006. Britta Lange examines the prevailing notions of „authenticity“ at the time, the portrayal of humans and animals, museology, enemy images and the film industry.

The founder of the first company under the name Umlauff that dealt with Ethnographica was Johann Friedrich Gustav (JFG) Umlauff (1833-1889), who went to sea as a young man, married a sister of the animal dealer Carl Hagenbeck in 1863 and started a company in Hamburg in 1868 with the name „Natural produce trade , shell goods factory, connected with a zoological-ethnographic museum“ (translated). The family business grew and moved repeatedly. Up to 1873 the company had apparently mainly obtained its stocks from ships calling at Hamburg , then the company switched to specifically commissioning departing seafarers, collectors, traders, etc. (S.145) After his death at the end of 1889, his widow continued the company with the help of Carl Hagenbeck and her eldest son Heinrich (1869-1925). The children working in the company specialized, young Heinrich in ethnology, but he was the real boss. In “Umlauff’s Weltmuseum” he developed a specialty of the company: so-called zoological-biological or ethnographic groups, i.e. scenes composed of life-size dolls, ethnographics and stuffed animals; the figures were  modeled on the basis of photos and plaster casts. There were also „Völkerschauen“ from the year it was founded. (S.147) According to the business books, the spectrum of the traded articles ranged from the forementioned zoologica, conchilia and ethnographica in various sizes, properties and numbers to anthropologica of all kinds (skulls, bones, brains and fetuses in alcohol). This means that, apart from plants, everything that a traveler brought with him from a distant country could be bought up and resold by the Umlauff company; often also live animals, which were then passed on to the Hagenbeck company or, if they did not survive the trip, as in many cases, were used by the zoological department anyway. The buyers of these various things were museums and scientific institutes of the corresponding disciplines as well as private collectors all over the world, including the then Dalai Lama. Another branch of advertising and business for the company was the organization or at least the posting of exhibitions on a wide variety of topics. (S.147/8)

modeled on the basis of photos and plaster casts. There were also „Völkerschauen“ from the year it was founded. (S.147) According to the business books, the spectrum of the traded articles ranged from the forementioned zoologica, conchilia and ethnographica in various sizes, properties and numbers to anthropologica of all kinds (skulls, bones, brains and fetuses in alcohol). This means that, apart from plants, everything that a traveler brought with him from a distant country could be bought up and resold by the Umlauff company; often also live animals, which were then passed on to the Hagenbeck company or, if they did not survive the trip, as in many cases, were used by the zoological department anyway. The buyers of these various things were museums and scientific institutes of the corresponding disciplines as well as private collectors all over the world, including the then Dalai Lama. Another branch of advertising and business for the company was the organization or at least the posting of exhibitions on a wide variety of topics. (S.147/8)

Thode-Arora quotes a letter from Heinrich Umlauff to Count Linden in Stuttgart in 1897:

„The Museum Umlauff … has the ethnographica partly collected by its own travelers at great expense, partly it acquires the same from casual collectors, or at auctions at home and abroad, or through the purchase of private collections“ (S.148) (Translation)

Business principles

Collections were preferably not torn apart, but only given in closed form, because well-documented items naturally increased their value. In the case of objects that were available in large quantities, however, this was not taken very seriously; for example, the jewelry was removed from a number of mummies before they were sold on to museums or showmen. Some of them were also provided with monkey hands and fish skin by the taxidermists, overmodeled and also sold to showmen as „mermaids“. (S.150) Heinrich Umlauff also set up ethnographic groups on loan in museums, which he later hoped to sell to these or other interested parties. (S.149)

An important action was the sale of two Maori meeting houses. Umlauff offered the first repeatedly to the Linden Museum in Stuttgart between 1902 and 1905, initially for 30,000 marks, later for 22,000 marks. Although he eventually conceded it to the Leipzig Museum, it appears to be the meeting house that is now in the Field Museum in Chicago. (S.150) (Sidney M.) Mead cites a booklet published in 1902 which apparently describes the house in Chicago. (S.151) Heinrich Umlauff asked for 35,000 marks for the second, which was acquired by the Hamburg Museum of Ethnology in March 1907. During the months of negotiations – including the installment payments – it was in the Hamburg free port.

An important action was the sale of two Maori meeting houses. Umlauff offered the first repeatedly to the Linden Museum in Stuttgart between 1902 and 1905, initially for 30,000 marks, later for 22,000 marks. Although he eventually conceded it to the Leipzig Museum, it appears to be the meeting house that is now in the Field Museum in Chicago. (S.150) (Sidney M.) Mead cites a booklet published in 1902 which apparently describes the house in Chicago. (S.151) Heinrich Umlauff asked for 35,000 marks for the second, which was acquired by the Hamburg Museum of Ethnology in March 1907. During the months of negotiations – including the installment payments – it was in the Hamburg free port.

From the correspondence (between Umlauff and the Hamburger Museum für Völkerkunde) it turns out that the issue of duplicates by the museum often served to settle invoices from the Umlauff company. Before 1914 ( museum director) Thilenius made conditional to sell such pieces outside of Europe or at least Germany, but in any case not to the Berlin Museum, certainly against the background that colonial officials preferred to sell ethnological objects to this museum. (S.151)

Adaptation to the crisis

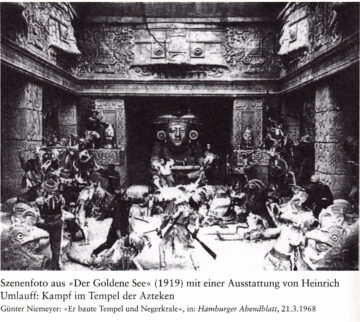

The First World War brought sales difficulties. Heinrich Umlauff now conceived and sent „war and booty exhibitions“; his modeled groups no longer showed foreign peoples, but soldiers with weapons. (151)

From 1918 on, Umlauff provided the decorations, costumes and props for  exotic feature films mostly of the Ufa Film-A.G. In 1921 Heinrich’s brother Johannes furnished Joe May’s „The Indian Tomb„, based on the novel by Thea v. Harbou, with 395 loans, which he requested from the Hamburg Museum of Ethnology. (S.152) Museum director Hellwig argued: “For our part, we think it is gratifying when the film companies endeavor to ensure that their screenings are carefully and faithfully furnished … on the other hand, however, we have to consider the risk that our holdings run, since after months of absence and frequent use the loaned objects cannot possibly be returned to us in the same, current condition … ”He followed up with the request for an extra instruction if the film should be successful. Koch-Grünberg from the Linden Museum refused a request to Umlauff in 1917: “But a film does not become scientific just because film actors or Hamburg port workers are draped in real costumes. This will not give ‚100 thousand‘ an ‚instruction‘, but will only deceive them and arouse false impressions. – Of course, our terms regarding ‚kitsch‘ differ widely. „(153)

exotic feature films mostly of the Ufa Film-A.G. In 1921 Heinrich’s brother Johannes furnished Joe May’s „The Indian Tomb„, based on the novel by Thea v. Harbou, with 395 loans, which he requested from the Hamburg Museum of Ethnology. (S.152) Museum director Hellwig argued: “For our part, we think it is gratifying when the film companies endeavor to ensure that their screenings are carefully and faithfully furnished … on the other hand, however, we have to consider the risk that our holdings run, since after months of absence and frequent use the loaned objects cannot possibly be returned to us in the same, current condition … ”He followed up with the request for an extra instruction if the film should be successful. Koch-Grünberg from the Linden Museum refused a request to Umlauff in 1917: “But a film does not become scientific just because film actors or Hamburg port workers are draped in real costumes. This will not give ‚100 thousand‘ an ‚instruction‘, but will only deceive them and arouse false impressions. – Of course, our terms regarding ‚kitsch‘ differ widely. „(153)

The year 1925 for the J.F.G Umlauf company

Heinrich Umlauf’s sudden death on December 22, 1925 (LINK) marked the decline of the company, which was soon in debt. At that time, the property portfolio comprised ca. 24,900 numbers with a value of 202,293 Reichsmarks, according to an estimate by (museum director) Thilenius, February 12, 1926. Thilenius judged the collections to be mostly average to in some cases very good and increasing in value …. Due to the lack of money, he advised Mr. Umlauff to give up his principle of only selling closed collections, because this would allow to sell „duplicates“ and develop a larger clientele; In addition, it creates space in the storage rooms …. Thecreditors should give Umlauff time and write to potential buyers directly. He was ready to use his personal relationships for this too. (February 15, 1926)

Although, according to the letterhead, Umlauff’s widow (Anita) had become the owner of the company, almost all of the letters … were addressed to her eldest son during this time, who – matching the company name – had been baptized Johann Friedrich Gustav. (S.154) He founded his own company sometime between 1928 and 1930. Until his death in 1942, the Museum für Völkerkunde was one of his customers, often through barter due to the tight financial situation of the Hanseatic city of Hamburg. (S.154)

As already mentioned before, the source situation for the activities of the various Umlauff companies of interest to ethnology leaves a lot to be desired, especially with regard to the heyday under Heinrich Umlauff’s leadership. (S.155)

– End of Part One –

What this essay changed in my head, I still can not say, with the exception of the lasting impression, how opaque were the sources of all museum collections, which inflated around the turn to the twentieth century. Realizing that things full of meanig landed as merchandise in large collecting tanks – maybe with a small label for the wrist – and were re-organized depending on the calculation of the dealer or the needs of the buyers, takes Provenance Research a lot of necessary hopeful breath. It’s not just about Carl Hagenbeck or J.F.G. Umlauff alone. The same way did Paul Guillaume in Paris in the Twenties (LINK – Look there for the essay of Andreas Schlothauer on the Coray Collection in „Art & Kontext“ 1/2016 (Link). And the other global players?

Question:

Is a structurally „modern“ production of „commercial goods“ morally higher than the state-ordered procurement of autochtons‘ cultural assets? Does it not result in a more radical devastation through dispersion and anonymization?

Further acquisition stories will follow. 16.Juli 2021