A Glimpse of Mangbetu Life

The Mangbetu are famous because of their style in architecture, furniture, weapons and tools, their well-known harps, decorated bark cloth, adornments, body-painting, skull deformation and extension of the eyelids, music and dancing on representative festivals.

The Mangbetu are famous because of their style in architecture, furniture, weapons and tools, their well-known harps, decorated bark cloth, adornments, body-painting, skull deformation and extension of the eyelids, music and dancing on representative festivals.

For a long time in the woody region , the Mangbetu had impressed the German researcher Georg Schweinfurth in 1870 with their fifty-meter-wide audience hall.

How they got along with the Arabs from the Sudan and the Sansibar coast, I do not know yet. In any case, they lost their power to the aggressive Azande from the north-west. Later the relations became so close that they exchanged their artists.

The figures are rare and made of light wood. The style is characterized by the beauty ideal of the aristocracy and their sense of decor. Even their homes were painted with geometric motifs.

(According to: Kerchache / Paudrat / Stephan: Die Kunst des schwarzen Afrika, Herder 1989, p.581 )

My interest is the long twilight of ancient African art, just as one could call an old European . They are still found in the village without electricity and traffic, but especially at the edges of the respective Megapolis, such as Kinshasa. There are also new African artists‘ careers: you just have to make some culinary tradition!

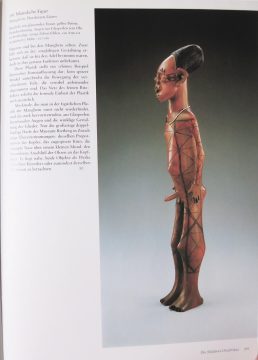

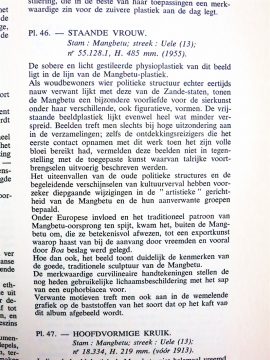

Werner Schmalenbach already published 1988 African art from the collection Barbier-Mueller , Geneva (no.190) a male figure of mangbetu (61 cm). It has it in itself. And I find in 2017 on the market a, felt, half as big (41 cm) male figure, which did not succeed. Would it have landed up with me? It is perfectly typical. A boy of irreproachable attitude, with crossed cross and a special gesture of the left hand.

Let us compare:

The two heads:

- – round giant ears – both figures

- – skull deformation by overhead plastering – also both

- – the nice pout – the other’s is more extreme

- – the snub nose with the visible nostrils – the other’s are bigger

- – a tattoo from ear to ear – not so nicely blackened

- – the straight neck – of course, the other’s is longer

- – interesting: almond eyes instead of eyes made of glass beads, which are imported from the East. Almond eyes are said to result from the formation of the skull and have been part of the beauty norm of the Mangbetu

Let us compare the bodies:

- – narrow round shoulders – both

- – geometric lines: broadly carved in notches instead branding which comes closer to the effect of body painting, plus additional diagonals,

- – delicate protruding navel and hollow cross

- – delicate penus, both – but with the ‚child ‚the scrotum is bigger

- – the buttocks of my figure are less pointed

The legs:

- – the legs not so extravagant, but in their brevity more ‚African‘, especially the thickening at the knees more ’naturalistic‘

- – the same applies to the feet, which seem to have been specially ‚reinvented‘ for the figure shown by Schmalenbach

- – As far as the length of the figure is concerned, it corresponds to the ideal of the dominant peoples from the east: Sudan, Uganda, Rwanda and Tanzania, also the Mangbetu?

In both cases, the patina shines ‚brown-yellow‘ (Schmalenbach), but the color-intensive image of the picture book can hardly be compared with the real figure, which in the open air already has a strikingly lighter tint.

And the Schmalenbach figure is strikingly fresh, except for a few lost toes. After all. I would have expected her to have gone directly from the workshop to Europe.

The accompanying text of EC (Enrico Castelli) appears conspicuously reserved for what is offered here:

Figures are rare in Mangbetu. From the careful design he concludes : destined for the nobility. But their precise function is unknown. The highly prominent existing eyes and the angular arrangement of the limbs are not typical for Mangbetu , but there is a harp in the Rietberg Museum which suggested that both objects are of the same artist or at least the same workshop. – Had the collector Mueller or his heirs nothing to contribute to the provenience of their figure even though they founded a renowned museum in Geneva?

Happened something like a “ Run“ of European collectors to certain artists of the Pende tribe (Katundu“ style) I have read of? After all, the mangbetu harps have been legendary for so long a time!

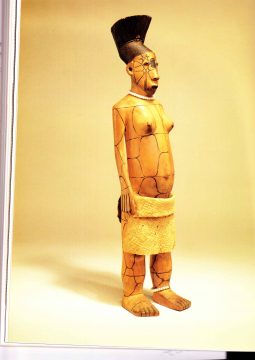

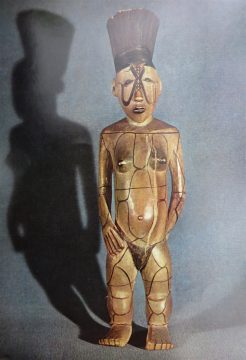

I have found three more figures, two women – one already acquired in 1910 – and another boy, all less eccentric.

Enid Schildkrout and Curtis A.Keim: African Reflections – Art from Nordeastern Zaire (1990)

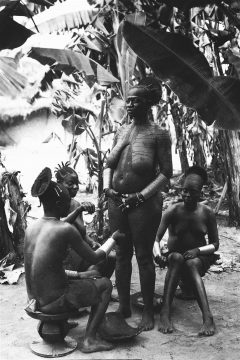

They show in the chapter The Art of Adornment a female figure of 43 cm height (collected in 1910) (ill 7.15). The face has similar plain shapes. And the sculpture has a similar aura. She is just as relaxed as the woman in the field photo (ill.7.16), which is being painted by girlfriends. Matubani, an impressive woman from the ruling class in Okondo’s village (1910) could have stood model for it, just not for the idealized breasts. In West Africa, by the way, we know such portraits of Dan and Baule women. The apron would be perfect for the boy figure too. The chapter provides an illustration (7.22; Azande) that it belonged to traditional men’s wear. We also learn by the text that it was collected in 1911-12, that the belt contains amulets and medicines, and that the ‚man‘ carries a simple hat of basket-braid. That’s all.

About body drawing

Mangbetu women of the ruling class painted their bodies with ‚bianga‘, a black juice extracted from the gardenia plant. The patterns were mainly geometric, like stars, crosses, dots and solid lines. New patterns were particularly admired. (commentary on 7.16)

The third figure, found in the art book „Umbangu“ from the late colonial period.

(2x Click to enlarge!)

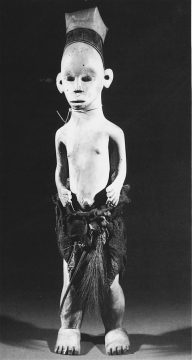

On Plate 46 of the representative collection is shown the Standing Woman Mangbetu , 47 cm (1955). The text – I try the translation with a Langenscheidt-Dutch-German dictionary – seems to be formulated in an ‚ur-Flemish‘ idiom, which Wallons and other ‚foreigners‘ should under no circumstances understand. Why else did they not add French or at least the neutral English?

The simple light-styled ‚body sculpture‘ of this portrait is on the line of Mangbetu sculpture. Asforest-dwellers and with a political structure similar to the Zande-states, the Mangbetu had a special predilection for „ornamentation“ among their various, also figurative forms. The free-standing sculpture was, however, less common. Figurines one meets at extraordinary (?) occasions during assemblies; Even the explorers who took the first contact …. did not mention these pictures, in contrast to the applied arts, of which numerous productions were described in detail.

The brake up of the old political structures and the accompanying phenomena of cultural decline implied deep changes in the „artistic“ (why are quotation marks here?) direction of the mangbetu and the related groups.

Soon after the beginning of European influence outside the Mangbetu …, which stood apart, an export art by strangers (came into being(?) ) occupied mainly by Boa.

However, this portrait sculpture clearly shows the characteristics of the good traditional sculpture of Mangbetu. The curious curvilinear drawings represent the still customary painting of the body with the juice of an euphorbicea. Related motifs are also found in the widely used graphics on textiles … „

To resume the result of our experimental deciphering: the esthetic judgment remains general, except mentioning of body painting. Has the author considered the sculpture only in terms of a naturalistic rendering of physical beauty norms of mangbetu, as a small-scale model? As a folkloric ‚costume doll‘?

That travelers like Georg Schweinfurth around 1870 did not see figures or considered them as insignificant, is interesting. About the social context we don’t get any information – and at the end of the colonial era. We read „Belgium’s art“ on the front page. On the exotic bent wooden glove „Umbangu“ is emblazoned in big letters .

The figure of a boy and the limits of gender

I have not yet seen a figure of an adult Mangbetu. Illustrations in old travel reports, however, suggest impressive ruling figures with corresponding attributes. The picture captions cited so far seem to blur the difference.

The boy’s sex is of early Hellenic grace. Even the high-rise figure of a young man at Schmalenbach (above, cat. 190) shows only an decently small erection of the penus.

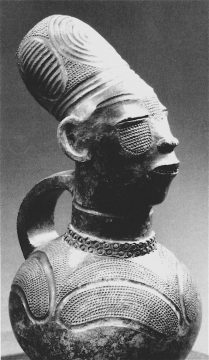

The face is undoubtedly childlike: from the big ears to the little snub nose, to the soft, slightly open mouth, which shows eight tiny incisors, like the head of the clay-jug at Kercheche-Paudrat (look picture on the bottom of the text). Since I do not know about a spiritual meaning of the large undifferentiated ears, they remind me of the photo showing a Mangbetu baby with big ears. The narrow sprotruding bean eyes are, incidentally, a secondary effect of the constriction of the child’s skull, and were thus judged to be ‚beautiful‘.

Above all, the aesthetic blurring of gender borders irritates: Would the boy become a ‚real man‘? His features still correspond more to those of beautiful girls and women, even to the details of stylization! Schmalenbach’s youth shows at least some power posing: ‚Thumbs at your trouser seams!‘ – but his body drawing is extremely playful. Mom or Aunt must have put his patience by long painting to the test! On my sculpture it is restricted to a few conspicuous right-angled lines – double drawn forward. Would that have been also fashionable for the Mangbetu woman? I leave the answer to you.

The boy’s attitude is serious, but it signals a attitude of patient expectation. His left hand, like the woman’s from the ‚Umbango‘ portfolio, rests on the buttock. He stands firmly on his carefully grooved feet. I wonder about the energy in the figure. It seems to be concentrated in it. – Thus, young initiates look like on field photos. Could this be an approach for interpretation, that is, the transition from the sphere of women and children to that of men? Did such figures relate to the initiation? Were young initiates decorated by their female relatives? And the gesture, had it is meaning in this context?

A Tourist Cultural Contact 1931

In 1931, two friends, the insect researcher Jiri Baum and the sculptor Vladimir Foit from Prague, crossed Africa from north to south in a car. They spent ten days in the village of the chief Ekibondo with his few hundred Mangbetu. Foit was supposed to model folk types for Prague’s Anthropological Museum. A „potter-widow“ gave them clay, but two young, totally unsophisticated men were introducing themselves as ‚local potters‘. Baum and Foit wondered about the poor craftmanship of the highly praised Mangbetu, but did not understand. People laughed at them. Women traditionally made pottery, different from the neighboring Azande villages. Later, in another village, Foit bought two clay figures in an open market in front of the government building: standing man and sitting women. The local seller offered to the tourists couples, which he had in several copies. These pottery figures reflected in style Mangbetu wooden sculptures. The objects ware so fragile that they were copied in Prague, in plaster.

In 1931, two friends, the insect researcher Jiri Baum and the sculptor Vladimir Foit from Prague, crossed Africa from north to south in a car. They spent ten days in the village of the chief Ekibondo with his few hundred Mangbetu. Foit was supposed to model folk types for Prague’s Anthropological Museum. A „potter-widow“ gave them clay, but two young, totally unsophisticated men were introducing themselves as ‚local potters‘. Baum and Foit wondered about the poor craftmanship of the highly praised Mangbetu, but did not understand. People laughed at them. Women traditionally made pottery, different from the neighboring Azande villages. Later, in another village, Foit bought two clay figures in an open market in front of the government building: standing man and sitting women. The local seller offered to the tourists couples, which he had in several copies. These pottery figures reflected in style Mangbetu wooden sculptures. The objects ware so fragile that they were copied in Prague, in plaster.

That is the story Joseph Kandert told in “ The Cultural Contact in the Mangbetu Forest“ , a contribution to the publication in honor of the 70th birthday of Armand Duchâteau: Faszination der Kulturen (Reimer Verlag 2001, p.147-154). I adressed an eMail to his actual czech university address but did’nt get an answer.

What can authentic ‚Mangbetu wooden sculptures‘ can mean?

When Kandert writes: These clay figures reflected stylistically wooden figures of Mangbetu , I would like to know what he knows about them.

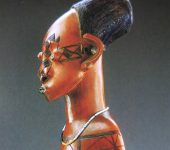

Finally, an author even claims – I’ll find the text again – that the famous ‚anthropomorphic‘  Jugs in the form of women’s heads were a clever business idea in the colonial era. Previously Mangbetu had been content with such jugs in geometric decor. The business idea may be true or not, these jars have become an esteemed feature of the Mangbetu in the world. And as they embody the aesthetic ideal of mangbetu, it is no wonder that they are found not only in collections and galleries, but also in large museums , and so also in Kerchache and Paudrat ’s Standard Work on Die Kunst des schwarzen Kontinents ( German Edition: Herder 1989, no. 653). >

Jugs in the form of women’s heads were a clever business idea in the colonial era. Previously Mangbetu had been content with such jugs in geometric decor. The business idea may be true or not, these jars have become an esteemed feature of the Mangbetu in the world. And as they embody the aesthetic ideal of mangbetu, it is no wonder that they are found not only in collections and galleries, but also in large museums , and so also in Kerchache and Paudrat ’s Standard Work on Die Kunst des schwarzen Kontinents ( German Edition: Herder 1989, no. 653). >

Authentic? What are the possible applications?

- Naturally, such as in the context of protection, promotion of birth, healing, etc., in the house or in the luggage of a magician, but as is known, figures are not necessary

- In the context of initiation, for example to teach (e.g. Lega)

- In memory of deceased who have passed into the spirit world – Is the boy perhaps dead? (e.g. twins‘ statuettes Yoruba)

- As part of a group in the context of a family treasure, which is publicly displayed at certain times – representation (e.g. Igbo)

- Gift to courtiers and distinguished guests of the prince

- Souvenir for travellers

This artful handle of a particularly refined five-string bow-horn from the Museum Barbier-Mueller, Geneva (Laure Meyer: Schwarzafrika 1992, Fig.185) represents the wide field of prestigious ‚everyday objects‘.

It shows stylistically typical details we know from the statuettes of the youths: Snub nose, big round ears, and a slightly open mouth with full lips, shovel hands, big feet and finally an elaborate radical geometrical body drawing, burnt in like the figure from Barbier-Mueller. Did these both objects come from the same workshop? The two museum publications do not provide any information on the acquisition.

William Rubin ( Primitivism , p.316) mentions „the omnipresence of modern and indigenous musical instruments in the cubist studios“ as early as 1911, because of the beauty of their abstract and lyrical forms. The Swiss art collector Josef Müller was since the end of the Twenties in Paris „one of the most important collectors of African art“. He united the fields of Classical Modernism and African and Oceanic Art ( Schmalenbach, op. p. 8) in the sense of the prevailing ‚Primitivism‘. (William Rubin). He was a typical representative of the Paris art milieu, as far as artistic sense and sources of supply were concerned.

14.6.17

Familenfoto von Rolf Italiaander in seinem Reisebuch „Vom Urwald in die Wüste“, erschienen 1955. Wer sich respektiert, pflegt die ästhetische Tradition:

14.9.2017 : Marc L. Felix: 100 Peoples of Zaire and their Sculpture 1987, 99 showed a couple of similar figures (no.1 and 2) and wrote:

„Mangbetu art in general is court-oriented, and was reserved for the ruling classes. Ir reflected the power, wealth, and prestige of its owners, and seems to be relatively secular rather than magico-religious. The few examples of 19. c. sculpture were found around the neighbouring Abarambo and the possibility of European influence on Mangbetu art productin is not to be discarded. A whole series of pieces were made to satisfy the New York Museum of Natural History expedition in 1910. Pieces we know we can ascribe to the Mangbetu are: figures purported to be representations of ancestors, either couples or single; …“