Fritz W.Kramer und Gertraud Marx : ‚Zeitmarken – die Feste von Dimodonko’ in der Reihe ‚Sudanesische Marginalien’ im Trickster Verlag, 189 Seiten, München 1993 (deutsch)

Fritz W. Kramer and Gertraud Marx: ‚Time marks – the festivals of Dimodonko‘ in the series ‚Sudanese Marginalia‘ published by Trickster, 189 pages, Munich 1993

The essay became a memorial for the people of ‚Dimodonko‘, the ‚Kodenko‘ or ‚Kronko‘ in the south of the Kordofan mountains. ‚Southern Nuba‘ was the term that caught my attention through frequent repetition in his Jensen memorial lecture at Frankfurt University in 2009 and was already a compromise with the language used in Germany, where ‚the Nuba‘ have long been a term. But basically Kramer, as a precise ethnologist, always meant ‚the people of Dimodonko‘.

The authors apologize for a philological approach – it is particularly evident in the introduction in lexical style, the notes and the long list of literature. Already in the first chapter, they give us an idea of how beautiful the book could have been, whose broad foundations we are admiring here. The result is a scientific paperback, with map sketches in irritatingly high resolution, but without pictures.

It is an intimate book, touching in its announcement that from now on the grammatical present tense will be used for past situations. How Fritz Kramer and Gertraud Marx would have loved to have experienced the entire annual cycle that they bring to life in the story, as well as the large and carefree celebrations that they were told about when they were invited to something like emergency editions in 1987. The intensity of the descriptions and discussions suggests that this period of classic field research between two acts of the civil war in southern Sudan was a formative experience, despite its premature end. The authors stayed with the people in 1987 for more intensive research, but the authors‘ first impression dates back to 1974. Back then, in those two decades, there was a great willingness to idealize alternative ways of life in West Germany. The book was published in 1993. Today I find it difficult to read the slim book in one sitting; I have long since lost the ability to tolerate social utopias. Any utopianism has been driven out of me.

The necessarily sketchy depiction offers a model of society and suggests, in summary, a ‚paradisiacal‘ state of ’noble savages‘ or, in Karl Marx’s words, a ‚primitive society‘ that made optimal use of the available resources in a small ecological niche – on the slopes of table mountains in the middle of the vast Sudanese plains. Embedded in nature – even if ‚hunger‘ or ‚malaria‘ had their place in the annual cycle – in general the circular character prevailed in everything. Communal work and enjoyment, the institution of ‚trusteeship‘ and finally an institutionalized ‚friendship‘ based on the inclinations of individuals, generally the consideration of human nature, especially gender and the need for intoxication or the channeling of creative and aggressive impulses in competition. How do you keep young people busy and happy with limited resources? A central question everywhere! All adversities of life, all human passions and peculiarities should be given meaning, made understandable. All possible conflicts should be, if not avoided, then at least embedded. That gave a lot to talk about. Life was never boring.

There were no formal hierarchies, not even those based on individual achievement. There was no more or less centralized rule. It was a culture in which the seasons were honored with festivals as ‚time markers‘ and social ties were thus periodically renewed. Corresponding motifs in ‚time markers‘ act like incantations: „…and celebrate their festivals, at which they hold wrestling competitions, play drums or lyres, dance and sing songs.“ (78). But there were people who left the nest, neighbors and, finally, supra-regional ‚modern‘ conflicts.

To see such a society collapse while efforts were being made to gain access and understand it must have been very painful. After a stopover with ‚Nuba‘ refugees stranded in Khartoum, they set about scientific reconstruction – on the shoulders of a few informants – with all the relevant literature in mind. There was too little space in the paperback for the ‚making of‘. The series of publications provided a sparse framework.

In the following two decades, Fritz Kramer has repeatedly illuminated and reflected on the culture of the people of Dimodonko in his publications, but from a rather increasing distance, as in his most recent book publication: Art in Ritual – Ethnographic Explorations on Aesthetics“ (in German), the elaboration of the 2009 lecture, published by Reimer Verlag in 2014.

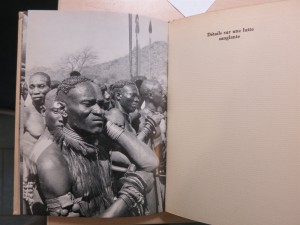

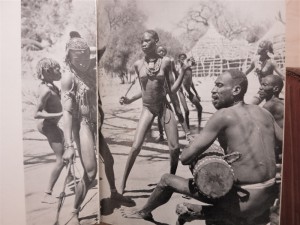

Documentary photos from Dimodonko are missing in ‚Zeitmarken‘. Visual experiences have to be obtained from elsewhere (literature list), but they are also from elsewhere. Even powerful literary prose cannot replace them.

The authors thus avoid a dilemma when they use strong metaphors alone to convey the cult of athletic, supple bodies and relaxed sensuality among the people of Dimodonko. Can attractive photos even successfully distance themselves from the suspicion of a ‚voyeuristic‘ gaze or a body cult labelled as fascistoid by a Leni Riefenstahl (‚Nuba‘)? I thought that the public scandal they caused thirty years ago (“SPIEGEL”, “STERN”) was exaggerated and I was curious to see the photos by George Rodger, which are referenced in the bibliography of “Zeitmarken”.

Image from G. Rodger, Le Village des Noubas, Paris 1955, Robert Delpire Editeur

See George Rodger: “On the road 1940-1949 – diary entries of a photographer and adventurer”, Hatje-Cantz 2009

See “Magnum Opus”, Nishen 1987, Colin Osman (ed.)

I can’t really see a relevant difference in the photographs, apart from the enormous step in the development of photographic and printing technology towards large-format color illustrated books. Image technology has generally become both more „voyeuristic“ and more „stylish“. To what extent does our judgment depend on the upgrading or downgrading of photographers?

In the case of Leni Riefenstahl, the unscrupulous perfectionist who achieved worldwide success with her maximization of sensual effects – staged for Hitler’s propaganda – and who, as an eighty-year-old photo tourist, only uttered platitudes about „Nuba“, a devaluation is obvious. In contrast, the documentary photographer of „Life“ and co-founder of the photo agency „Magnum“ (LINK) Rodgers has our sympathy, who after 1945 sought inner distance from traumatizing encounters such as that with the victims of the concentration camp „Bergen-Belsen“, when he undertook a long adventure trip with his wife through Africa in 1949, which his diaries openly recount. Who would think of „voyeurism“ in his recordings?

The book by Fritz Kramer and Gertraud Marx is thirty years old. They write in their foreword: „The state in which we last saw the Kodonko was one of anxious waiting, in which the hope for a return of peace prevailed. (….) For the Kodonko distinguished between good and bad times, which alternate, and for them the present war was not the one-off event that might put an end to their world, but a moment in the return of the same. The good time was the time to celebrate the festivals as they fall, the bad time their forced suspension. ….“ (p.9, January 1993)

George Roger shows and describes a local disaster in the village of a neighboring Nuba group: a fire caused by an overturned cooking pot, which, with flying sparks, turned two hundred and thirty houses into a pile of charred ruins within thirty minutes and destroyed the grain supplies for the next year. (“On the road…” p.105, March 3, 1949, Kau)

The connection to the people of the Nuba Mountains has long been severed. Their state of “forced suspension” continues. Even after “South Sudan” forced its separation from “Sudan” in 2015 after twenty years of war, war is still raging in the Nuba Mountains north of the new state border. This story of burned villages, resettlements and violent expulsions is summarized in Wikipedia “Nuba” and described in a recent interview in the Catholic weekly newspaper for the diocese of Berlin with the striking name “Tag des Herrn” (https://www.tag-des-herrn.de) from January 2nd, 2019

Text excerpt:

Interview with doctor and missionary Tom Catena – The forgotten conflict in southern Sudan

Conflicts on all sides, but forgotten internationally: The people in the Nuba Mountains in southern Sudan are poor, their needs receive little international attention. Aid organizations rarely venture into the region. The doctor and missionary Tom Catena built a hospital there around 10 years ago. In the interview, the award-winning doctor from the USA talks about the difficult situation and health care in the region.

Mr. Catena, your hospital is in the Nuba Mountains in southern Sudan on the border with South Sudan. What is the situation like there?

Officially, the Nuba Mountains belong to Sudan. But the area is controlled by rebels, the Sudanese Liberation Army. They are fighting against the Sudanese government in Khartoum and demanding independence. We in the Nuba Mountains live in limbo. It is currently quiet, but nobody knows in which direction the political situation will develop and whether fighting will break out again. (….)

The hospital is the only one for around a million people.

Yes. Our catchment area is roughly the size of Austria. Some patients come from refugee camps in South Sudan, others scattered from the mountains. Many travel for several weeks to reach us.

Sudan is one of the poorest countries in the world. Can people even afford treatment?

The patients pay a symbolic contribution of 45 cents. This is basically a flat rate for the entire treatment. However, this does not even come close to covering the costs. By comparison: an HIV test alone costs 60 cents. Most of it is covered by donations. The hospital’s operating costs are around 660,000 euros. We employ 230 people, 80 of whom are nurses. Many of them have no proper training, but were trained on the job.

Where do you get medicine and what else you need?

It’s complicated. But at least since the peace agreement between Sudan and South Sudan in 2015, goods have been reaching us fairly reliably. We buy the medicine in Nairobi in Kenya. It is then driven to South Sudan. There is a single road there that brings everything – goods, food or medicine – to us in the mountains. If there is trouble there, we are cut off from supplies.

Do you feel forgotten or left alone?

Sudan and the Nuba Mountains are a forgotten conflict. The United Nations has left the region and no longer has a foot in the door. But when governments and institutions fail, individuals have to fill the gaps and look after the people. That is exactly what happened in Nuba. I see it as part of my job not only to provide medical help, but also to draw attention to the conflict.

The people there have no one else to speak for them and stand up for them.

Why not? In times of migration, Africa already plays a strategic role for Europe… Sudan was demonized internationally for a long time and was considered a terrorist state. The migration crisis in Europe has changed that, but one-sidedly. Many refugees from Eritrea are moving to Libya via Sudan and want to go from there to Europe. The EU pays Sudan a lot of money to stop migrants on their way. The regime often acts brutally.

What do you expect from the EU?

The EU should think about where money can be used sensibly. Because in large parts of Sudan, nothing is currently reaching the people themselves. Most people there have only known war for years and are fed up with it. A peace agreement between Sudan and the rebels in the mountains would help them. This is something that should be promoted internationally. Sudan is officially a Muslim state and you belong to the Christian minority – does this affect your work? The coexistence of Muslims and Christians in the Nuba Mountains is unique. Christians form a fairly large minority there. There is not really a religious divide. Some Muslims are married to Christians and vice versa. For fundamentalists in the north, however, the Muslims in the Nuba Mountains are therefore considered infidels. (….)