ORIGINAL : „DUALA“ (6) : Kamerun – Vom Treuhänder in die Unterentwicklung geführt – DEUTSCH (24.5.2021) (LINK) + 2 acaps „Briefing notes: 21-january-20 and 29 june 2023

Preface

Admittedly, I have a hard time with the political chapters (5) and (6) of this blog. A broad topic that can hardly be seen through from the outside, and which can make you angry or depressed, depending on your point of view. What I, as a contemporary of the 20th century, had noticed from the colonialism of Europe – especially France – shows its ugly face again in the current long-term consequences. Hence the sarcastic headline.

Certes, j’ai du mal avec les chapitres politiques (5) et (6) de ce blog. Un sujet large que l’on ne voit guère de l’extérieur, et qui peut vous mettre en colère ou déprimé, selon votre point de vue. Ce que moi, en tant que contemporain du XXe siècle, avais remarqué du colonialisme de l’Europe – en particulier de la France – montre à nouveau sa grimace dans les conséquences actuelles à long terme. D’où le titre sarcastique.

HISTORY

The impression that solidified during the readings shall be confirmed by El-Hussein Aw and Prosper Akouegnon at the end of the Blog as concept of the French governments since the 1950s. That in no way means that our friendly neighbor should bear sole responsibility for Cameroon or the misery of Africa. But I think it is fundamentally wrong to make the subject taboo or to make it unrecognizable by politicians‘ diplomatic lies.

L’impression qui s’est solidifiée lors des lectures sera confirmée par El-Hussein Aw et Prosper Akouegnon à la fin du Blog comme concept des gouvernements français depuis les années 1950. Cela ne signifie en aucun cas que notre voisin ami doit porter seul la responsabilité du Cameroun ou de la misère de l’Afrique. Mais je pense qu’il est fondamentalement faux de rendre le sujet tabou ou de le rendre méconnaissable par les mensonges diplomatiques des politiciens.

The „independence movement“ in Cameroon and its defeat

The “MARKK” museum at Rothenbaum in Hamburg is currently devoting to the Duala Manga Bell an emotionally warm exhibition aimed at young people (LINK), catalog optionally in English!). Still, I don’t want to start with the day of his execution at the beginning of the murderous „World War“ in Europe. With the conflict over their ancestral property in the center of Douala, the urban Duala elite experienced firsthand the violence of the colonial conquest that other peoples of Cameroon suffered from for years. The fact that the German colonial masters were soon exchanged, confused allegiances after 1919 and prevented common resistance. Europe, weakened by wars and revolutions, held the conquered colonies for another forty years – and beyond.

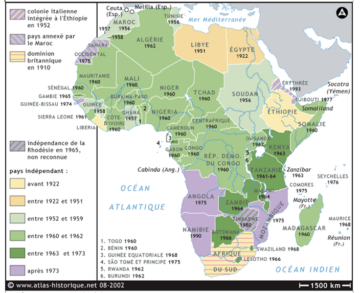

The modern independence movement of Cameroon began with the demand for immediate and complete independence immediately after World War II and in the now global crisis of European colonial domination “The independence movement was led by an elite trained at the University of Dakar (Senegal) and supported by a national bourgeoisie and urban workers experienced in protest” (P. Morazán, 14). Their political party was the UPC (Union de la Population camerounaise), founded in 1947, which insisted on the UN’s renewed assurance of a time limit on the „trusteeship“ of France and Great Britain. But France succeeded in eliminating the UPC, a process that dragged on until 1972 despite the limited social base of the ‘communist’ cadre party. They were forced into illegality as early as 1955. Their guerrillas were defeated in a locally limited colonial war. The functionaries were driven into exile and/or murdered, as in 1960 Dr. Félix-Roland Moumie (* 1926 Fumban) through poison (!) In Geneva. The UPC called for a merger with the British-administered Southwest early on and warned of an impending “neo-colonial future of Cameroon”. de Gaulle has been quoted as saying that no one in this world could achieve complete independence (L.H.Aw). This may be true, but it does not erase political and economic “abuse of control”. At most, Europe could blame the few evicted colonies, but how long did this situation last?

The government of Cameroon, which became formally independent in 1960, not only extended the state of emergency declared in 1958 and continued to employ French administrative officials, teachers, military personnel and torturers. She also took over the enemy image of the UPC and completely erased the organization from public memory for decades until 1991 (Ketzmerick p.208-9).

Le «mouvement indépendantiste» au Cameroun et sa défaite

Le musée «MARKK» de Rothenbaum à Hambourg consacre actuellement au Duala Manga Bell une exposition chaleureuse et émotive destinée aux jeunes (LIEN), catalogue en anglais en option!). Pourtant, je ne veux pas commencer par le jour de son exécution au début de la meurtrière «guerre mondiale» en Europe. Avec le conflit sur leur propriété ancestrale dans le centre de Douala, l’élite urbaine Duala a vécu de première main la violence de la conquête coloniale dont d’autres peuples du Cameroun ont souffert pendant des années. Le fait que les maîtres coloniaux allemands aient été bientôt échangés, a confondu les allégeances après 1919 et a empêché une résistance commune. L’Europe, affaiblie par les guerres et les révolutions, a tenu les colonies conquises pendant encore quarante ans – et au-delà.

Le mouvement d’indépendance moderne du Cameroun a commencé avec la demande d’indépendance immédiate et complète juste après la Seconde Guerre mondiale et dans la crise désormais mondiale de la domination coloniale européenne. «Le mouvement indépendantiste était dirigé par une élite formée à l’Université de Dakar (Sénégal) et soutenu par une bourgeoisie nationale et des ouvriers urbains ayant une expérience de protestation» (P. Morazán, 14). Son organisation politique était l’UPC (Union de la Population camerounaise), qui a insisté sur l’assurance renouvelée de l’ONU d’une ‚tutelle‘ temporaire de la France et de la Grande-Bretagne. Mais la France a réussi à éliminer politiquement et militairement l’UPC – une lutte difficile qui a dépassé l’indépendance formelle malgré la base sociale limitée du parti des cadres aux influences communistes Déjà depuis 1955, l’UPC était „illégal“, une guerre coloniale locale cachée etait menée contre leur guérilla, les fonctionnaires ont été poussés à l’exil ou assassinés, le Dr Félix-Roland Moumie déjà en 1960 à Genève par le poison (!)

l’UPC appelait à une fusion avec le sud-ouest administré par les Britanniques mettait le Camerounais en garde contre un «avenir néocolonial» imminent Cameroun ». de Gaulle aurait déclaré que personne dans ce monde ne pouvait obtenir une indépendance complète (L.H.Aw). C’est peut-être vrai, mais cela n’efface pas «l’abus de tutelle» politique et économique. Tout au plus, l’Europe pouvait rejeter la responsabilité des quelques colonies expulsées, mais combien d’années cette situation a-t-elle duré?

Le gouvernement du Cameroun, officiellement indépendant en 1960, a non seulement maintenu l’état d’urgence déclaré en 1958 et a continué d’employer des fonctionnaires de l’administration, des enseignants, des militaires (et des tortionnaires) français. Elle adopte également l’image ennemie de l’UPC et a complètement effacé l’organisation de la mémoire publique pendant trois décennies (Ketzmerick p.208-9).

Remember the international context for the actors at the time.

After liberation from German occupation, France had tried militarily to regain Indochina for ten years, which ended in a catastrophe in 1954. At the same time, a brutal colonial war began in Algeria, even France’s conscript youth were drafted. This defeat was not yet sealed when the French state released Cameroon and the other African colonies (except Guinea) – reluctantly but according to a comprehensive plan – into neo-colonial bogus independence (P. Akouegnon). Domestically, France was weak, the inflation of the franc galloped, the governments changed ‚weekly‘ and in 1958 the military staged a coup in favor of General de Gaulle, who founded the Fifth Republic and re-established France’s role as a ‚middle power‘ globally. To do this, La France urgently needed her former colonies in Africa (Saw). At that time, the Cold War intensified with the Soviet Union, leading to the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1961 and the erection of the “Berlin Wall” in Germany and proxy wars. The UN was divided and incapacitated, as demonstrated during the terrible civil war in the former Belgian Congo. The Committee overseeing the trust areas nodded off France’s plans for Cameroon and, of course, betrayed the Cameroon peoples, whom the UN had promised full decolonization.

Il faut se souvenir du contexte international des acteurs de l’époque.

Après sa libération de l’occupation allemande, la France avait tenté de regagner militairement l’Indochine pendant dix ans, ce qui s’est soldé par une catastrophe en 1954. Au même moment, une guerre coloniale brutale a éclaté en Algérie, et même les jeunes conscrits de France ont été enrôlés. Cette défaite n’était pas encore scellée lorsque l’Etat français a libéré le Cameroun et les autres colonies africaines (à l’exception de la Guinée) – à contrecœur mais selon un plan global – dans une fausse indépendance néocoloniale (P. Akouegnon). Sur le plan intérieur, la France était faible, l’inflation du franc galopait, les gouvernements changeaient „ chaque semaine “ et en 1958 l’armée a organisé un coup d’État en faveur du général de Gaulle, qui a fondé la Ve République et rétabli le rôle de la France en tant que „ puissance moyenne “. «globalement; pour cela, La France avait un besoin urgent de ses anciennes colonies en Afrique. (Vu) À cette époque, la guerre froide s’est intensifiée avec l’Union soviétique, conduisant à la crise des missiles de Cuba en 1961 et à l’érection du «mur de Berlin» en Allemagne et à des guerres par procuration. L’ONU était divisée et bloquée, comme en témoigne la terrible guerre civile dans l’ancien Congo belge. Le comité de supervision des zones de confiance a ignoré les plans de la France pour le Cameroun et, bien sûr, «a trahi le peuple camerounais, à qui l’ONU avait promis une décolonisation totale.

October 1961: “Southern Cameroons” joins the “République Cameroun” .

„Southern Cameroons“, the south of a border strip of Cameroon, which had been administered for almost forty years as part of the British colony of Nigeria, joined the République Cameroun, which has been independent since January 1960, after a referendum and a meeting of the respective heads of government. I have read somewhere that the population felt neglected by the British colonial administration and chose the supposedly progressive former French colony after a separate state independence seemed unattainable. Above all, the ‘anglophone’ elite received the promise to rule an autonomous part of the state while maintaining the official language English, the British educational and legal system, all under the federal constitutional structure of the Octobre 1961: «Southern Cameroons» rejoint la «République Cameroun» (janvier 1960). Le „Southern Cameroons“, au sud d’une bande frontalière du Cameroun, qui avait été administrée pendant près de quarante ans dans le cadre de la colonie britannique du Nigéria, a rejoint la République Cameroun, indépendante depuis janvier 1960, après un référendum et une réunion des chefs de gouvernement respectifs. J’ai lu quelque part que la population se sentait négligée par l’administration coloniale britannique et avait choisi l’ancienne colonie française prétendument progressiste après qu’un État indépendant séparé semblait inaccessible. Surtout, l’élite «anglophone» a reçu la promesse de diriger une partie autonome de l’État tout en maintenant la langue officielle anglaise, les systèmes éducatif et juridique britanniques, le tout sous la structure constitutionnelle fédérale République fédérale du Cameroun („un Etat autonome de langue anglaise au sein d’une fédération binationale“).

Octobre 1961: «Southern Cameroons» rejoint la «République Cameroun».

Le „Southern Cameroons“, au sud d’une bande frontalière du Cameroun, qui avait été administrée pendant près de quarante ans dans le cadre de la colonie britannique du Nigéria, a rejoint la République Cameroun, indépendante depuis janvier 1960, après un référendum et une réunion des chefs de gouvernement respectifs. J’ai lu quelque part que la population se sentait négligée par l’administration coloniale britannique et avait choisi l’ancienne colonie française prétendument progressiste après qu’un État indépendant séparé semblait inaccessible. Surtout, l’élite «anglophone» a reçu la promesse de diriger une partie autonome de l’État tout en maintenant la langue officielle anglaise, les systèmes éducatif et juridique britanniques, le tout sous la structure constitutionnelle fédérale de la République fédérale du Cameroun, « état autonome de langue anglaise au sein d’une fédération binationale ».

Were there no doubts about the constitution?

Who in Yaoundé or Paris actually came up with the bilinguisme institutionel, the “institutionalized bilingualism”, this daring construct for a newly founded multiethnic state without state tradition? Nobody would have thought of that by European standards, only later to the European Union for the divided Balkans. An extremely centralized France had previously done everything to bind ‘their’ colonies to itself forever, primarily through the French language and legal and educational systems! Who actually believed the bad joke back then or pretended to believe it? And why?

N’y avait-il aucun doute sur la constitution?

Qui à Yaoundé ou à Paris a inventé le «bilinguisme institutionnalisé», cette construction audacieuse d’un État multiethnique nouvellement inventé sans tradition étatique bien fondée? Au contraire, une France extrêmement centralisée avait auparavant tout fait pour enchaîner à jamais «ses» colonies à elle-même, principalement par le monopole de la langue française et de son système juridique et éducatif! Qui croyait vraiment à la mauvaise blague à l’époque ou prétendait y croire? Et pourquoi?

Two Dictators, two Eras

With Ahmadou Ahidjo, a sympathetic young Muslim politician from the north, a Peul, whom France had appointed as Prime Minister of the transitional government in 1958, Cameroon’s first President renwed all the special powers of the „state of emergency“ into „independence“, with the argument of „internal security“ (Ketzmerick). He gradually introduced a presidential dictatorship and merged various parties already friends of France to form the “UC” unity party. In May 1972, he organized a referendum (99.9% approval result) to make the Federal Republic a United Republic of Cameroon. With seven administrative provinces instead of four, the English-speaking southwest was already degraded. ,Then a powerless Assemblée Nationale replaced the federal pseudo-parliaments. The first and second presidents, Paul Biya, have since ruled the state by government decree.

After moving from the post of Prime Minister to the Presidency of the President in 1982, Paul Biya continued the policy of creeping marginalization of „Anglophones“ through systematic discrimination. This also included symbolic acts: in 1984, he removed by decree the term „united“ from the name of the state as the last trace of the 1961 constitution. Since then, representatives of the English-speaking movements have vehemently called for a return to federalism of the first constitution,“ taking into account the cultural duality of Cameroon „. President Biya refused in 1990 again to legalize the English-speaking political party. It was not until 1992 that he organized elections between several parties under the pressure of mass demonstrations (for example in Douala) due to a serious economic crisis and last but not least of the “Paristroika” hype, the democratic movement of French-speaking Africa. However, that did not stop Biya from continuing to rule in 1992 and 1997, but also in 2004, 2011 and 2018 – as an „election winner“ in his fictitious democracy. During his thirty-year reign he became famous for his political inactivity – the Prime Minister, currently a Southwestern man, takes care of day-to-day affairs anyway. To this day, Biya spends much of the year with his ‚court‘ in Geneva and rarely shows up in Cameroon. But France is next.

Deux dictateurs, deux époques

Avec Ahmadou Ahidjo, un jeune politicien musulman sympathique du nord, un Peul, que la France avait nommé Premier ministre du gouvernement de transition en 1958, le premier président du Cameroun a étendu tous les pouvoirs spéciaux de l’état d’urgence au-delà de «l’indépendance». avec l’argument de la «sécurité intérieure» (Ketzmerick). Il introduit progressivement une dictature présidentielle et fusionne divers partis déjà amis de la France pour former le parti d’unité «UC». En mai 1972, il organisa un référendum (résultat d’approbation à 99,9%) pour faire de la République fédérale une République-Unie du Cameroun. Avec sept provinces administratives au lieu de quatre, le sud-ouest anglophone était déjà dépassé. Dans tous les cas, une assemblée nationale impuissante a remplacé les pseudo-parlements «fédéraux». Le premier et le deuxième présidents, Paul Biya, ont depuis dirigé l’État par décret.

Après être passé de la fonction de Premier ministre à la présidence du président en 1982, Paul Biya a poursuivi la politique de marginalisation rampante des «anglophones» à travers une discrimination systématique. Cela comprenait également des actes symboliques: en 1984, il a supprimé le terme «uni» du nom de l’État comme dernière trace de la constitution de 1961. Depuis lors, les représentants des mouvements anglophones ont réclamé avec véhémence un retour au «fédéralisme» de la première constitution, «en tenant compte de la dualité culturelle du Cameroun». Le président Biya a refusé en 1990 encore de légaliser le parti politique anglophone. Ce n’est qu’à partir de 1992 qu’il organise des élections entre plusieurs partis sous la pression de manifestations de masse (par exemple Duala) en raison d’une grave crise économique et enfin et surtout dans le climat «Paristroika», le mouvement démocratique d’Afrique francophone. Cependant, cela n’a pas empêché Biya de continuer à gouverner en 1992 et 1997, mais aussi en 2004, 2011 et 2018 – en tant que «vainqueur des élections» dans sa démocratie fictive. Au cours de ses trente années de règne, il est devenu célèbre pour son inactivité politique – le Premier ministre, actuellement un homme du Sud-Ouest, s’occupe de toute façon des affaires quotidiennes. À ce jour, Biya passe une grande partie de l’année avec sa cour à Genève et se présente rarement au Cameroun. Mais la France est à côté.

A „binational“ language dispute?

Labeling the ongoing conflict between the southwest and the rest of the country as a language conflict between „Francophonie“ and „Anglophonie“ can be misleading. Because the languages spoken among the population are not in conflict, as the detailed and sober study „Cameroun – République du Cameroun – Republic of Cameroon“ by the Laval University shows. But the ‚Anglophone minorities‘ are encountering practical obstacles everywhere. They were already part of the region at a time when the name “Cameroon” did not even exist or only referred to the coastal strip dominated by the Duala. At that time – until 1884 – the English influence was dominant, that of other European nations ephemeral. When the Germans came, there was fierce competition for a few decades, but the new masters often had to use the common pidgin English when dealing with their subjects. Based on ‚African‘ grammars and with ‚polyphonic‘ vocabulary, this has been the lingua franca in the entire south of Cameroon since the 19th century and has now even broken down into regional and social offshoots. See «Camfranglais».

LIONEL JEAN tells us more details on the relationship between the languages in Cameroon:

Two hundred tribal languages registered in Cameroon (langues nationales or camerounaises) are spoken less and less from generation to generation and are disappearing. With exceptions, they have never been taught in schools and are no longer researched since 1990 (L. Jean). They are still used on the radio for the roughly 40% illiterate population in the countryside. In their command of one of the two state languages, urban and rural populations differ greatly, which is related to school attendance. The official school languages are being ’nationalized‘ under local influences. The command of the ’second official language‘, English, does not help individuals outside their region at all, neither in their careers nor in relation to the authorities. According to the linguist Lionel Jean (Laval), the fact that English has not completely disappeared from Cameroon is due to his international „strategic“ position. (L. Jean, 39)

„In general, Cameroonians see themselves primarily as French or English-speaking. If the state is bilingual, its citizens don’t have to be, because a bilingual state does not necessarily imply bilingual people. For example, the vast majority of Canadians and Belgians have remained monolingual , while their central state is bilingual. (…) Francophones are generally more bilingual (approx. 25%) than Anglophones (approx. 20%). As a result, efforts to speak the other official language remain shy, while pidgin English takes precedence over the official languages. “ (Lionel Jean, translated)

„The use of pidgin English is more popular than French and English combined, especially in the entire southwest and in the capital Yaundé. It is the Cameroonian language that you can find in the market, in church, at the doctor’s, at the police station and used in the capital’s offices. Some politicians don’t even hesitate to speak to their potential voters in pidgin English, and state radio uses it in emergency situations. Although this „bush English“ («anglais de brousse») is officially banned and hated by many, it seems to be a ’necessary evil‘ in this country where multilingualism is omnipresent „.

„The use of pidgin English is more popular than French and English combined, especially in the entire southwest and in the capital Yaundé. It is the Cameroonian language that you can find in the market, in church, at the doctor’s, at the police station and used in the capital’s offices. Some politicians don’t even hesitate to speak to their potential voters in pidgin English, and state radio uses it in emergency situations. Although this „bush English“ («anglais de brousse») is officially banned and hated by many, it seems to be a ’necessary evil‘ in this country where multilingualism is omnipresent „.

(Lionel Jean, 39, translated)

Un conflit linguistique «binational»?

Les langues parlées au sein de la population ne sont pas en conflit, comme le montre l’étude détaillée et sobre «République du Cameroun -» de l’Université Laval (https://www.axl.cefan.ulaval.ca/afrique/cameroun.htm). Les «minorités anglophones» faisaient déjà partie de la région à une époque où le nom de «Cameroun» n’existait même pas ou faisait uniquement référence à la bande côtière dominée par les Douala. A cette époque – jusqu’en 1884 – l’influence anglaise était dominante, celle des autres nations européennes éphémère. Lorsque les Allemands sont arrivés, il y a eu une compétition pendant quelques décennies, mais les nouveaux maîtres ont souvent dû utiliser le pidgin anglais commun pour traiter leurs sujets. Basée sur des grammaires «africaines» et sur un vocabulaire «polyphonique», elle est la lingua franca dans tout le sud du Cameroun depuis le XIXe siècle et se décompose même en ramifications régionales et sociales. Voir «Camfranglais».

LIONEL JEAN nous raconte plus de détails sur la relation entre les langues au Cameroun:

Deux cents langues nationales ou camerounaises enregistrées sont de moins en moins parlées de génération en génération, et certaines disparaissent. Sauf exceptions, ils n’ont jamais été enseignés dans les écoles et ne font plus l’objet de recherches depuis 1990 (L. Jean). Ils sont toujours utilisés à la radio pour les quelque 40% de la population analphabète des campagnes. Dans leur maîtrise de l’une des deux langues officielles, les populations urbaines et rurales diffèrent considérablement, ce qui est lié à la fréquentation scolaire. Les langues officielles de l’école se «nationalisent» sous les influences locales. La maîtrise de la «deuxième langue officielle», l’anglais, n’aide pas du tout les personnes extérieures à leur région, ni dans leur carrière ni en relation avec les autorités. Selon le linguiste Lionel Jean (Laval), le fait que l’anglais n’ait pas complètement disparu du Cameroun est dû à sa position «stratégique» internationale. (L. Jean, 39)

En général, les Camerounais se considèrent principalement comme francophones ou anglophones. Si l’État est bilingue, ses citoyens ne sont pas obligés de l’être, car un État bilingue n’implique pas nécessairement des personnes bilingues. Par exemple, la grande majorité des Canadiens et des Canadiennes Les Belges sont restés monolingues, alors que leur État central est bilingue. (…) Les francophones sont généralement plus bilingues (environ 25%) que les anglophones (environ 20%). Par conséquent, les efforts pour parler l’autre langue officielle restent timides , tandis que l’anglais pidgin a la priorité sur les langues officielles.

La coexistence légalement obligatoire de deux systèmes juridiques et systèmes éducatifs européens échoue, notamment lorsqu’il s’agit d’offrir aux personnes qui y vivent les mêmes chances de réussite. Les «minorités anglophones» recontrent partout des obstacles pratiques.Les candidats «anglophones» du sud-ouest se voient systématiquement discriminés et empêchés d’avancer dans la fonction publique. «Dans l’armée, seul le français est admis. Les anglophones et pidginophones doivent donc devenir bilingues.» ( L. Jean 30)

2019 – 2021

The Biya regime has been promising a “dialogue” with English-speaking Cameroon since 2019 only. In the meantime, politicians are already calling for secession and armed militias violently blackmail the rural population into an “education strike” against “the programs of the Ministry of Education in Yaoundé”. Displacement due to the armed conflict is alarming. The preconditions for dialogue are therefore very unfavorable. (See David Signer and the ACAPS Education Report)

Le régime Biya promet un „dialogue“ avec le Cameroun anglophone depuis 2019 seulement. Entretemps des politiciens appellent déjà à la sécession et des milices armées font violemment chanter la population rurale en une „grève de l’éducation“ contre „les programmes du ministère de l’Éducation à Yaoundé“. Les déplacements à cause du conflit armé sont alarmants. Les conditions préalables au dialogue sont donc très défavorables. (Voir David Signer et le rapport sur l’éducation de l’ACAPS)

SITUATION ACTUELLE selon ACAPS

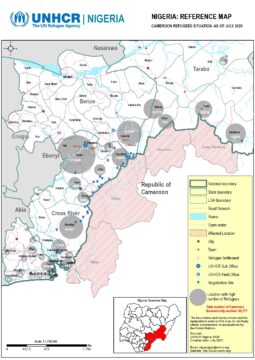

acaps 21-january 2020 20200121_acaps_short_note_escalation_of_the_anglophone_crisis_cameroon_0.pdf – with map of Cameroon „Escalation of the Anglophone crisis“ (Separatist fighters, limited success of Swiss mediation efforts, refugees

acaps 29 June 2023 (20230629_ACAPS_Cameroon_cholera.pdf) „Increase in cholera cases“ (coincides with a crisisin the health system, conflict and displacement, overview)

Neocolonialism „all-inclusive“

„France’s post-colonial sub-Saharan policy presents itself as a complex, contradicting and, in terms of motives and consequences, controversial mixture of colonial ties, geopolitical calculations, economic interests and cultural awareness of mission.“ (El-Hussein Aw p. 83)

The topic of France’s Africa policy has little presence in the German public. Even the Bundeswehr’s appearance in Mali only occasionally makes it into the print media, and even less so into the government-related public television. In Cameroon, the various connections to France are of course omnipresent. El-Houssein Aw – Excerpts from his study (2005) and in “Mémoire Online” The Aw’s study provides us with a common thread to bring this confusing and, especially in the first few years, rapidly changing situation into a certain order. At this point, the following information – including the summary of the basic agreement of 1960 with the colonies – must suffice.

Independence under certain conditions

Michel Débré, General de Gaulle’s Prime Minister, wrote on July 15, 1960 to the Gabonese President-elect Léon M’ba: “Independence is granted on the condition that the state, once independent, undertakes to comply with the previously signed cooperation agreements. There are two systems that operate at the same time: the independence agreement and the cooperation agreements. One cannot be done without the other. I would be grateful if you would confirm by confirming receipt of this communication that the Government of the Gabonese Republic will continue to sign cooperation agreements after the proclamation of independence. The text was initialed that day and steps will be taken immediately to ensure that it comes into force. It goes without saying that it will be the same on the part of the Government of the French Republic. “ (translated from: Aw Online)

“The foreign policy agreements, the only ones concluded in the form of state treaties requiring ratification, can serve as the basis for the entirety of the cooperation agreements. In the agreements on military cooperation, a fundamental distinction was made between defense and technical military aid agreements. The defense agreements concluded with eleven states provided for agreements on all questions relating to external security and granted France the right to maintain military bases and to use the military infrastructure. In return, Paris assured the African governments ‚pour leur défense contre toute menace‘ (sic!) – also against internal threats – support. The secret conventions on the maintenance of internal order and security are said to have stipulated a formal request from the French government as a prerequisite for the deployment of French troops. – During de Gaulle’s reign, seven former African colonies underwent a change of power or coup d’état. – (….) The Technical Military Agreements obliged France to support thirteen of its fourteen successor states in building up their own armed forces. The African states parties agreed to turn exclusively or primarily to France for the procurement, maintenance and renewal of weapons and other war material. Defense cooperation agreements also included agreements on strategically important raw materials and products. They envisaged a common raw materials policy and obliged the African countries to export crude oil, natural gas, uranium, thorium, lithium, beryllium, helium as well as ores and their compounds en priority to France and to help the French armed forces with their storage ”. (ibid.)

“The most important agreements in terms of economic policy and associated with an obvious loss of sovereignty concerned currency relations. In functional contrast to the politico-territorial balkanization of the region, they provided for the supranational regulation of monetary relations within the framework of the franc zone, a structure that is still unique in the world today, which guarantees fourteen sovereign states a common currency – the CFA franc – whose convertibility is the French treasury ensures. “ (ibid.)

“The cultural agreements that shaped the elite were also of lasting importance in terms of political influence. In them, the states of Francophone „Africa“ pledged to retain French as the official language and instrument of their development „and to turn to France as a priority to meet their needs for teachers. Settlement conventions, agreements on cooperation in judicial angling units and personal assistance in setting up state structures completed the agreement. “ (ibid) “As the result of a peaceful decolonization process, which was largely regulated by contractual agreement, the bilateral contractual system of cooperation guaranteed the continuity of Franco-African relations by aligning the political and economic structures of Francophone Africa with the former colonial power. The majority of the agreements, renegotiated in the mid-sixties and early seventies, have survived to this day and form the contractual framework for an astonishingly amicable relationship. “ (Aw Online)

CLICK twice!

Néocolonialisme ‚tout compris‘

El-Houssein Aw – Extraits de son étude (2005) et sur «Mémoire en ligne»:

„La politique sub-saharienne postcoloniale de la France se présente comme un mélange complexe, contradictoire et, en termes de motifs et de conséquences, controversé de liens coloniaux, de calculs géopolitiques, d’intérêts économiques et de conscience culturelle de la mission.“ (El-Hussein Aw p. 83)

La politique africaine de la France est peu présente dans l’opinion publique allemande. Même grâce à la participation de la Bundeswehr au Mali, elle ne parvient qu’occasionnellement à la presse écrite et encore moins à notre télévision trop proche du gouvernement. Au Cameroun, les différents liens avec la France sont bien sûr omniprésents.

L’étude de l’Aw nous fournit un fil conducteur pour ramener cette situation déroutante et, surtout au cours des premières décennies, en évolution rapide dans un certain ordre. Les informations suivantes – y compris le résumé des accords de base de 1960 – ne peuvent que donner une idée.

Indépendance sous conditions

Michel Débré, Premier ministre du général de Gaulle, écrivait le 15 juillet 1960 au président élu gabonais Léon M’ba: « On donne l’indépendance à condition (sic !) que l’Etat une fois indépendant s’engage à respecter les accords de coopération signés antérieurement. Il y a deux systèmes qui entrent en vigueur simultanément : indépendance et les accords de coopération. L’un ne va pas sans l’autre. (…) Je vous serais obligé de bien vouloir, en accusant réception de cettte communication, me confirmer que, des la proclamation de l’indépendance de la République gabonaise, le gouvernement de la République gabonaise procédera à la signature des accords de coopération…, actes dont le texte a été paraphé en date de ce jour et qu’il prendra aussitôt les mesures propres à assurer leur propre entrée en vigueur. Il va de soi qu’il en sera de même de la part du gouvernement de la République française.« (citation : Aw Online avec sources d’information, note* 157)

«Ces accords de politique étrangère, qui étaient les seuls conclus sous la forme de traités d’État à ratifier, peuvent servir de base à l’ensemble des accords de coopération. Dans les accords de coopération militaire, une distinction fondamentale a été faite entre les accords de défense et d’aide militaire technique. Les accords de défense conclus avec onze Etats prévoyaient des accords sur toutes les questions relatives à la sécurité extérieure et accordaient à la France le droit d’entretenir des bases militaires et d’utiliser les infrastructures militaires. En retour, Paris a assuré aux gouvernements africains «pour leur défense contre toute menace» (sic!) – également contre les menaces internes – leur soutien. Les conventions secrètes sur le maintien de l’ordre intérieur et de la sécurité auraient stipulé une demande formelle du gouvernement français comme condition préalable au déploiement des troupes françaises. – Pendant le règne de de Gaulle seulement, sept anciennes colonies africaines ont subi un changement de pouvoir ou un coup d’État. – (…. ibid.)

Les Accords Technico-Militaires ont obligé la France à soutenir treize de ses quatorze Etats successeurs dans la constitution de leurs propres forces armées. Les États parties africains ont convenu de se tourner exclusivement ou principalement vers la France pour l’acquisition, l’entretien et le renouvellement des armes et autres matériels de guerre. Les accords de coopération en matière de défense comprenaient également des accords sur des matières premières et des produits d’importance stratégique. Ils ont envisagé une politique commune des matières premières et obligé les pays africains à exporter du pétrole brut, du gaz naturel, de l’uranium, du thorium, du lithium, du béryllium, de l’hélium ainsi que des minerais et leurs composés en priorité vers la France et à aider les forces armées françaises dans leur stockage. ». (ibid.)

«Les accords les plus importants en termes de politique économique et associés à une perte évidente de souveraineté concernaient les relations monétaires. En contraste fonctionnel avec la balkanisation politico-territoriale de la région, ils prévoyaient la régulation supranationale des relations monétaires dans le cadre de la zone franc, structure encore unique au monde aujourd’hui, qui garantit à quatorze États souverains une monnaie commune – le franc CFA – dont la convertibilité est assurée par le Trésor français. „(ibid.)

«Les accords culturels qui ont façonné l’élite étaient également d’une importance durable en termes d’influence politique. En eux, les États de l’Afrique francophone se sont engagés à conserver le français comme langue officielle et instrument de leur développement „et à se tourner vers la France en priorité pour répondre à leurs besoins en enseignants. Conventions de règlement, accords de coopération en matière de pêche judiciaire des unités et une assistance personnelle dans la mise en place des structures étatiques ont complété l’accord. „(ibid.)

The Jacques Foccart System

El-Hussein Aw : A central figure in French Africa policy was basically Jacques Foccart until his death in March 1997. In 1960 he became General Secretary of the Communauté Française and, after independence, Secrétaire général à la présidence de la République. This position, equipped with far-reaching power and exclusive privileges (direct access to de Gaulle, daily meetings in the evening), was retained even under Pompidou, although his power was reduced. Foccart had direct influence on the appointment of ambassadors, viewed copies of the diplomatic mail, controlled the Chefs de mission d’aide et coopération and issued – by means of encrypted codes and in the presence of the Foreign Ministry – directives and instructions. Jacques Foccart achieved everything that he achieved in the African sphere of influence of France with the help of numerous networks (…) (Aw Online, edited; they are supplemented by page 18 of the study:)

“One of the most important tasks of Foccart was the direct contact with African elites and the representation of the French influence interests. In addition to his private business connections, which he stuck to despite his political office, he benefited above all from his knowledge as coordinator of the French secret and intelligence services. In trustful consultation with de Gaulle, he loyally implemented his instructions, advised African heads of state, received agents from the secret service SDECE every day and coordinated the Africa policy of the French bureaucracy in weekly secret meetings. In addition, he received the accredited French ambassadors in African countries and managed over 2500 visits from African ministers a year (according to Alfred Grosser 1990). „

Le système Jacques Foccart

Une figure centrale de la politique de l’Afrique française était essentiellement Jacques Foccart jusqu’à sa mort en mars 1997. En 1960, il devient secrétaire général de la Communauté française et, après l’indépendance, secrétaire général à la présidence de la République. Cette position, dotée d’un pouvoir de grande envergure et de privilèges exclusifs (accès direct à de Gaulle, réunions quotidiennes le soir), a été conservée même sous Pompidou, bien que son pouvoir ait été réduit. Foccart a eu une influence directe sur la nomination des ambassadeurs, a consulté des copies du courrier diplomatique, contrôlé les chefs de mission d’aide et de coopération et émis – au moyen de codes cryptés et en présence du ministère des Affaires étrangères – des directives et des instructions. Jacques Foccart a réalisé tout ce qu’il a réalisé dans la sphère d’influence africaine de la France avec l’aide de nombreux réseaux (…) (Aw Online, édité; complété par la page 18 de l’étude 🙂

«L’une des tâches les plus importantes de Foccart était le contact direct avec les élites africaines et la représentation des intérêts d’influence français. En plus de ses relations d’affaires privées, auxquelles il a tenu malgré sa fonction politique, il a surtout bénéficié de ses connaissances en tant que coordinateur des services secrets et de renseignement français. En consultation confiante avec de Gaulle, il a fidèlement mis en œuvre ses instructions, conseillé des chefs d’État africains, reçu chaque jour des agents des services secrets SDECE et coordonné la politique africaine de la bureaucratie française lors de réunions secrètes hebdomadaires. En outre, il a reçu les ambassadeurs de France accrédités dans les pays africains et a géré plus de 2500 visites de ministres africains par an (selon Alfred Grosser 1990) „

9.2. 2022 Recommendation

Chapter IV „Cameroon: silence, we kill“ in „Les Dessous de Franc’afrique“ (LINK to radiofrance.com) by Monsieur X and Patrick Pesnot (Nouveau Monde editions, Paris 2008) is

written lively and concisely but in a differentiated manner in easy French. It offers a portrait of the founder of the UPC, of the UPC and its massive oppression, and of the Foccard system, e.t.c.

Le chapitre IV „Cameroun : silence, on tue“ dans „Les dessous de Franc,afrique“ (LIEN à la ) de Monsieur X et Patrick Pesnot (Nouveau Monde éditions, Paris 2008) est

rédigé de manière vivante et concise mais différencié dans un français lisible,. Il propose un portrait du fondateur de l’UPC, de l’UPC et de son oppression massive, et du système Foccard, e.t.c.

BIBLIO. : 17 good links on the net / 17 liens sur le net :

HISTORY, POLITICS / HISTOIRE, POLITIQUE

- Caroline Authaler : „UNABHÄNGIGKEIT FÜR WEN? DIE WENIG GLANZVOLLE UNABHÄNGIGKEIT IN KAMERUN” 20. Oktober 2010 · 2 S. in SCHWARZWEISS (Post-)Koloniales, Geschichten (LINK)

- Victor Julius Ngoh : „The political evolution of Cameroon, 1884-1961“ Portland State University, Diss. 1979 136 pp. (LINK to pdf)

- Pedro Morazán : “Kamerun: Die Kehrseite der Globalisierung – Koloniales Erbe, Armut und Diktatur” SÜDWIND Edition Strukturelle Gewalt in den Nord-Süd-Beziehungen – Band 4, Siegburg März 2005, 72 S. – ein Institut, das für kirchliche Hilfswerke tätig ist. (Link zum pdf). Economic historical analysis of Cameroun as a model case of undesirable developments

- Maria Ketzmerick „Staat, Sicherheit und Gewalt in Kamerun“ (deutsch) –

The political science doctoral thesis (2019) provides the chronicle of Cameroon’s “postcolonial state building” together with the rhetoric used at the time in the external presentation to domestic or western public. In the corresponding situational context, even mortally boring quotes from government-related newspapers and politicians‘ speeches become interesting. This sounds familiar to the reader, since the claim of „threatened security“ combined with „everything under control“ is becoming a political instrument used more and more inflationarily not only by dictatorships. The de-Gruyter-Verlag/transcript-Verlag has uploaded chapter 6.4 as open source (LINK). La thèse de doctorat en sciences politiques (2019) fournit la chronique de la «construction de l’État postcolonial» au Cameroun ainsi que la rhétorique utilisée à l’époque dans la présentation externe au public national ou occidental. Dans le contexte situationnel correspondant, même les citations mortellement ennuyeuses des journaux gouvernementaux et des discours des politiciens deviennent intéressantes. (Citations en français!)

- (de.)Wikipedia offers several interesting articles about Cameroon, under keywords as “Cameroon”, “Ahmadou Ahidjo”, “Paul Biya, „History of Cameroon“ e.t.c.

Critical and well-written articles by journalists / Articles bien écrits par des journalistes:

- Deutsche Welle – «Co-auteurs: Moki Kindzeka, Henri Fotso» „60 years of independent Cameroon – and no festive mood For many Cameroonians, France is still omnipresent – even if it has been independent for six decades. They believe that the mistakes of the past are today have led to crises. “ (translated by Gv) «60 ans de Cameroun indépendant – et pas d’humeur festive Pour de nombreux Camerounais, la France est toujours omniprésente – même si elle est indépendante depuis six décennies. Ils croient que les erreurs du passé ont conduit à des crises aujourd’hui.“ (traduction Gv) (LINK)

- David Signer : “Die Lage in Kamerun ist katastrophal – Die Uno berät über die Krise in den anglofonen Provinzen“; Neue Züricher Zeitung am 18. Mai 2019 (LINK )

- BBC 5.10.2018 : “Paul Biya: Cameroon’s ‘absentee president’” (LINK)

- Jefcoate O’Donnell, Robbie Gramer : “Cameroon’s Paul Biya Gives a Master Class in Fake Democracy”, foreign policy October 22, 2018 (LINK)

POLITIQUE DE LA FRANCE EN AFRIQUE

- El-Houssein Aw : „Perspektiven einer neuen französischen Afrikapolitik im frankophonen Afrika südlich der Sahara“ , Freie Universität Berlin – Master in Political Science am Otto-Suhr-Institut 2005 – Le lien présente le chapitre 3 et mène à l’originale, aussi en langue allemande pour 4 € (PayPal): Télécharger le fichier original (LIEN)

- Prosper Akouegnon : “Les 11 composants des Accords post coloniaux avec la France”,

publié le 7 octobre 2016 dans son blog journalistique «AfricTelegraph – L’info africaine indépendante», qu’il dirige depuis le Gabon: (LIEN). –J’ai lu en détail les traités dans une étude politologique il y a trente ans ou plus, à l’époque pour mon unité d’enseignement sur le Sénégal, mais avec le temps cela s’est oublié.

LANGUAGES, EDUCATIONAL SYSTEM / LANGUES, SYSTÈME ÉDUCATIF

- Cameroun – République du Cameroun – une monographie de l’Université Laval au Canada sur l’histoire nationale, le développement et la diffusion des langues, 42 pages, des cartes spéciales et des liens, mise à jour en 2019. Seul le linguiste Grammarien Lionel Jean est nommé co -auteur. (LINK pour télécharger un pdf)

- ACAPS A thematic Report vom 19, Februar 2021 “Anglophone Crisis in Cameroon – Impact on education in the Northwest and Southwest regions” of the information service for NGOs based in Geneva (LINK)

THE TWO LEGAL SYSTEMS

- For a systematic account of the split “Cameroon Legal System” see the article by Henry, Samuelson & Co. in HG.org Legal Ressources (LINK)

(All addresses were checked on 16 May 2021)

*

ANNEX FOR NON FRENCH SPEAKERS

“Les 11 composants des Accords post coloniaux avec la France”

by Prosper Akouegnon October 7, 2016 in „AfricTelegraph“ (translated Extracts)

Prosper: “In this article, we will detail the eleven main components of these agreements, signed just with independence. And which are still in effect. And applied to the letter by our states …

-

Colonial debt for reimbursement of the benefits of colonization (….)

-

Automatic confiscation of national financial reserves – African countries must deposit their financial reserves with the Banque de France. France has thus „kept“ the financial reserves of fourteen African countries since 1961: Benin, Burkina Faso, Guinea Bissau, Côte d’Ivoire, Mali, Niger, Senegal, Togo, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, Congo-Brazzaville, Equatorial Guinea and Gabon. (…..)

-

The right of first refusal on any raw or natural resource discovered in the country

France has the primary right to purchase the natural resources of the land of its former colonies. (….)

-

Priority to French interests and companies in public procurement and public tenders

In the award of public contracts, French companies have priority over award. Even though African countries can get better value for money elsewhere. (….)

-

Exclusive right to supply military equipment and train military officers of the colonies

Thanks to a sophisticated system of scholarships, grants, and the „defense agreements“ attached to the colonial pact, Africans must send their senior officers for training in France. (…..)

-

The right for France to deploy troops and intervene militarily in the country to defend its interests: By virtue of what are called „the defense agreements“ attached to the colonial pact, France has the right to intervene militarily in African countries, and also to station troops permanently in military bases and installations, which are fully managed. speak French. (….)

-

The obligation to make French the official language of the country and the language of education – Yes sir. You must speak French, the language of Molière! An organization of the French language and the dissemination of French culture has even been created. It is called the „Francophonie“ and has several satellite organizations. These organizations are affiliated and controlled by the French Minister of Foreign Affairs. (….)

-

The obligation to use the CFA franc (franc of the French Colonies of Africa) (….) When the euro currency was introduced in Europe, other European countries discovered the French operating system. Many, especially the Nordic countries, were dismayed; they suggested that France get rid of the system, but without success.

-

The obligation to send to France an annual balance sheet and a reserve status report. No report, no money. (….)

-

Renounce any military alliance with other countries, unless authorized by France (….)

-

The obligation to ally with France in the event of war or global crisis – Over a million African soldiers fought for the defeat of Nazism and fascism in World War II. Their contribution is often ignored or minimized. „(…..)