German original: August 27, 2015 plus Supplement Sept. 03,2018 (LINK); revised translation November 13,2020

Some Nigerian entrepreneurs in Lagos collect works of art from African cultures. Due to their geographic location, their collections do not have access to the international cartel of influential museums, auction houses and collectors. The art historian Sylvester O. Ogbechie presents the collection of Feti Akinsanya as representative.

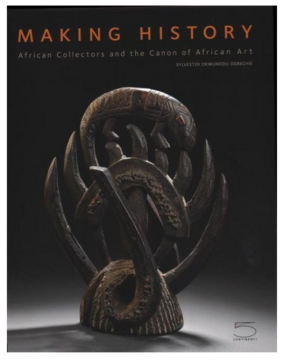

Sylvester Okwonudu Ogbechie: ‚Making History – African Collectors and the Canon of African Art‘: The Femi Akinsanya African Art Collection. (Five Continents 2011)

Making History – a high standard!

The art book of Editions 5 Continents, Milano focuses on the neat, conventional depiction of handsome objects. Excellent state of preservation, dark patina and well-kept colors predominate, as well in the case of the Primitive Art objects from the eastern parts of Nigeria. A front view is presented on dark, neutral background, neither rear views nor details.

This ‘coffee table book’ attracts attention because of its programmatic title which refers to a polemical essay by Sylvester Ogbechie. In the first three chapters it provides concise information about Collecting Art in Lagos and Akisaya the Collector and his Art Dealers, but above all it provides some rhetorical mirror-fencing that should not be read first. The core of the matter is revealed only in the following two chapters: The Olowe Corpus and Yoruba Sculpture and Benin Artworks and the Discourse of Authenticity. They take up two thirds, almost forty pages, of the essay interspersed between the panels.

The crux of the matter: The Quest for Authenticity

The fourth chapter is about canonical Master Olowe and the attribution of collection objects to him. Dedicated Lagos entrepreneurs – and their traders – are competing fiercely with one another, according to Ogbechie. In the topic they are interested not only for scientific reasons. They prove to be by no means immune to the alleged offers from counterfeiters who can deliver a dream work. Akinsanya tells about a friend (143) who bought a clumsy fake (from a Haussa!). Surprising carelessness after the described circumstances. So everything as usual.

I find the chapter Benin Artwork and the Discourse of Authenticity more interesting because it neatly summarizes a special dodgy collecting area in its historical dimension. The famous Benin bronzes were already ’rare’ as exclusive products for the King from strictly organized purveyors to the court. The term artwork used is accurate because Benin had been in contact with Europe for five hundred years and the objects were not even considered as primitive art there (178). And the monarchs of Europe organized their representative art not differently.

Ogbechie already defines these bronzes as hybrid and concludes convincingly: the Benin bronzes of the 20th century cannot be assessed otherwise. What does that mean in conclusion for the ‚originals‘ before 1897? For me they are technically admirable handicrafts in the old European sense.

Victimized

Ogbechie, as a member of the royal family, who was dethroned by the English in 1897 and dispossessed of their artworks, I ‚buy’ his personal resentment at the art theft. In the lecture ‘Rethinking the Canon‘ (Ogbechie on youtube), he speaks of his fantasy of maybe encountering an object in a gallery that he should actually be entitled to and not even being able to provide evidence for that.

On the other hand, he knows what ‚war‘ and ‚booty‘ – especially those of symbolic political relevance (here: regalia, rulership insignia) – mean in history. He himself speaks unmoved of the old Benin as a predatory and slave hunter state, of the fact that the kingdom as a major player had been a flourishing trading center for the transatlantic slave trade for centuries. (174ff.). Some of these figures were cast from imported metal and were thus physically part of the dirty business. Ogbechie is undoubtedly justified in denouncing ‚the expropriation of Africa‘, its plundering by colonial and post-colonial Europe, but I find his moral pathos exaggerated, especially since he represents Nigerian nationalism, Edo patriotism and the interests of marketing at the same time. So he represents a lot of strong egoisms. In the end, he equates cultural wealth with economic value and frankly admits that he prefers to see the ‘value’ of these products ’privatized and capitalized by African owned collections than by people outside Africa. (228) A matter of opinion.

Control of Art Canon and Art Discourse

In this context, the aim is to wrest from abroad the monopoly of control over the art discourse, in particular over ‚the transformation‘ of African cultural objects into works of art (228): The Canon, that is at odds with the reality of Africa’s creative traditions with the traditional and contemporary contexts (218)? At first I was amazed how violently Ogbechie attacked a „canon“ created on the basis of the colonial collections. Apparently the history of the Benin bronzes explain that, as the British booty has become the benchmark among experts and connoisseurs. 1897 became the epochal date. Under these circumstances, no further ‚original’ would be allowed to ‘appear in Africa. Above all – according to Ogbechie – the international art trade callously refuses to recognize and appreciate the bronzes that were created after the kingship was overthrown.

Artificially limited supply or free market access?

As Ogbechie describes the situation, it is much more confusing:

The successors of the dethroned ruler still placed orders with their purveyors to the court, but these were now allowed to supply the elites of other ethnic groups and play their role there. According to the social/ritual use criterion of ethnologists, these products were also originals. Commercially, exports to customers abroad became even more important. With the figures considered so far, the formal quality can be mentioned due to the unbroken training tradition. Then there were technical innovations. Finally, the traditionally trained foundries began to sign their works after 1970 to distinguish them from the many Edoid bronzes circulating on the art market. However, some combined a second training at an art school with traditional apprenticeship and broke new stylistic territory themselves. For Ogbechie even the manufacturers of edoid or beninoid mass-produced goods do not have to be excluded as tourist art (177), even if they do not belong to the diaspora.

Who can look through this in individual cases? The collector and author are both committed and competent in this field. Benin bronzes have been popular with collectors in the Nigerian intelligentsia since the nationalist phase 1950-1970. And they have ‘old’ would-be masterpieces (David Lerner LINK), including Akinsanya. Ogbechie discusses the status of individual bronzes owned by Akinsanya over many pages and sums it up: “… Above all, they are impressive original artworks and African art studies can no longer justify putting such important examples of Benin’s cultural continuity beyond the pale of discourse.“ (205)

Two articles in ‘African Arts’ from 2012 give a vivid description of the history and situation of the ‘Benin Brass Casting’ industry in Benin City. After that, Ogbechie’s political and scientific positioning can also be understood more easily. (See my addendum from September 3, 2018)

My question: Is the spell on Benin bronzes from Nigeria collections now broken? I have not yet heard of an exhibition abroad.

What role do ‚higher‘ values play?

The term cultural continuity has a real political background in today’s Benin (Nigeria). Leaving the colony, the British pragmatically handed over the small ethnic groups to the large – like Ibo and Yoruba – and the ‚declassed‘ rulers continue to fight for an adequate political participation to this day. ‚Culture‘ is an important argument here.

In addition, Ogbechie is promoting the Benin bronzes as national treasure as part of a world heritage (173). Although he tends to blame foreigners and strangers for all problems (e.g. Hausa for fakes and mass-produced goods), he uses this opportunity to address a few home-made problems – far too briefly: Defective legal system (lack of protection of property rights to traditional African art), lack of recognition by the still indifferent political class. After all, the population of Nigeria must be won over as protectors against the hateful destruction of art by fundamentalist fanatics among Muslims and Christians (ibid.). Only then does local art have a strong potential to contribute to nation building (111) – fifty years after the country’s independence! May be. But how?

The kinship of remote areas remains speechless here

The book itself does not much to promote nationbuilding. The objects created outside of Ife and Yoruba fill in the author’s introduction and conclusion. They are represented by stereotypes: ‘20th century’ and ’peoples’ (“Isoko peoples’ for example). Only the sizes of the objects are more informative. After all, the author refers kindly to the recently published American standard work „Central Nigeria Unmasked“ (Fowler Museum at UCLA, 2011). Especially with the objects from the eastern outskirts of Nigeria, information about the provenance would have been helpful, even if provenance does not represent a general key to the secrets of a figure. Akinsanya is cited as an example of a new „openness“ that should serve as a model for an branch operating in the shadows. He is cited to be informed by the suppliers. So then he must know more about his collectibles. (117) Or does he not learn more about it than we do in Europe or America?

Two articles on Contemporate Benin Brand Brass Castings in African Arts

Joseph Nevamdomsky: “Iconoclash or Iconostrain – Truth and Consequence in Contemporate Benin Brand Brass Castings” African Arts vol. 45, no.3 pp.14-27

John Ogene: “The Politics of Patronage and the Igun Artworker in Benin City”, ibid. Vol.45, no.1 pp.42-49

Like Ogbechie, Nevamdomsky criticizes Western art history for drawing the line between epochs in 1897 and failing to acknowledge and to document production in the 20th century. He emphasizes the continuity and further development of the arts and crafts after an interruption that was not a catastrophe. The kingdom, which was re-established in 1914, took the guild under its wing and at the same time opened them a viable path to local and foreign customers. The workshops have diversified, with the traditionalists having to live with the suspicion that their copies are seen as fakes. They would be if they were patinated to old-fashioned European taste by Haussa dealers. Local customers prefer the bright brass tone, but are also open to new ideas in terms of form and theme.

New customer groups among the nouveau riche and politicians in Nigeria order portrait heads, also based on photos so that they look more like the honored or deceased. This is illustrated very nicely by John Ogene.

Perhaps, if collectors love Benin bronzes, why not send photos and have portrayed themselves in a brass finish for reasonable $ 5000.

November 13, 2020:

John Pemberton III – A far more prominent review reviewed again !

Sylvester O. Ogbechie’s interest in my review gives me the motivation to read again the review by John Pemberton III, a famous expert on the arts in Nigeria, in H-Net Reviews, and to comment on it.

On the first two pages Pemberton mentions the collector’s Akinsanya travels among Benue villages and strict requirements for his nigerian dealers. „One of the most important aspects of his collecting was (and is) his increasing concern for ‚authenticity‘. Not only did Akinsaya want to know the context in which an object was used and had its value for indigenious peoples, but he insisted that the dealers he relied upon knew the family and community history of an object, as well as the social and ritual contexts in which it was used, and he insisted that their information be verifiable.” That will probably be the case, but none of that got into the book.

My keen interest in the peripheral Benue peoples was part of my disappointment, and particularly with this aspect of the book.

Pemberton himself turns his attention to two complexes that Ogbechie places at the center and which enjoy first priority in the Art Market: the examination of the sculptural genius of Olowe of Ise (Ikerre-Ekiti) and the Benin bronzes in the Akinsaya Collection, including the wide range of contemporary Edoid bronzes, also by African diaspora people. His remarks about the social / ritual use of all kinds of artworks by Africans and African Diaspora people and the migration of objects and aesthetic forms seem to be common sense today. However, they serve in a subordinate role his plea for a change of attitude among Western art historians.

He fully supports Ogbechie’s intention „to realize the limitations and dangers in the concept of“ canon „and the need for an awareness of the cultural and historical determination of the cultual and historical determination of our understanding of creativity in the visual arts of Africa.“

Dear Laurena

You remind me of the actuality of Ogbechie’s arguments. Thanks. He may have a small chance of getting family property back if the documentation is not burned in 1897 and the agreements between German museums and the state of Nigeria provide for this.

On the other hand, he can hardly be pleased that the hype about restitutions appararently confirms the star cult around that corpus of royal artwork ‚before‘ 1897 by the international art trade cartel. He wrote in the interests of African art collectors as well as artisans in Benin City. German cultural politicians don’t see this ‚collateral damage‘ at all. Detlev 3.7.22