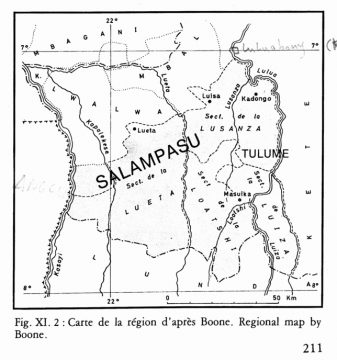

The title is pure irony. The Salampasu in the south of the DRC on the border with Angola have a bad reputation. After all, a man could only gain reputation there over centuries as a hunter, warrior and cannibal. And the peope later were reluctant to reveal family secrets to curious strangers.

Would modern Europeans approuve ?

Modern Europeans may develop certain sympathies for these ‘eccentrics‘:

The Salampasu defended themselves stubbornly against the influence of their big neighbors as Lunda or Luba ‘kingdoms’, which of course were also keen on the oil palms and iron deposits of the area around Luiza. And they succeeded in their fight as extremely decentrally organized ethnic group (acephale). Their members jealously guarded their individual freedom and were only temporarily united by external threats. Who does not think of the legendary Gallic village in “Asterix and Obelix”?

Or would you prefer a less humorous comparison?

As with the Spartans of greek antiquity, the man strived hard for honor. Rules worked so effectively that status and wealth were practically not inherited. In the the organisation of hunters and warriors, the mungongo, one had to show courage in hunting and in war, kill enemies and eat their bodies, but also had to invest his fortune to rise in the hierarchy satisfying the members of higher ranks.

Women had different priorities. they would not rely upon their husbands, but more about that later. They had to live – „patrilocal“ – in the husband’s village, but their children belonged to the her lineage and they inherited – „matrilinear“ – their maternal uncle. The Salampasu trace their ancestry and name back to a legendary founder and her six daughters – to the delight of Western followers of a „matriarchy“ !

The villages were in constant dispute as economic and political competitors, they even waged war against each other. This gave recently initiated young warriors and ambitious adult men the opportunity to excel, to rise in rank and boost their own magical powers by the newly acquired secret knowledge.

In short, Salampasu were no joking matter. After all, deterrence was their capital!

I do not want to go on describing ‘the good old days’ of the Salampasu. They ended in the 1880s with the invasion of the Chokwe from the south, who drove by force larger peoples too, such as the Pende to the Kasai River far north. For centuries, Lunda and Luba had aimed in the expansion of their empires at some loose supremacy. The brutal war-style of the Chokwe, however, was no match for the Salampasu as it was focused on plunder and prey. From then on, the Salampasu gave up some of their ‚Spartan‘ equality to establish permanent dynasties of rich families, accepting some degree of the Lunda centralized rule.

I do not want to go on describing ‘the good old days’ of the Salampasu. They ended in the 1880s with the invasion of the Chokwe from the south, who drove by force larger peoples too, such as the Pende to the Kasai River far north. For centuries, Lunda and Luba had aimed in the expansion of their empires at some loose supremacy. The brutal war-style of the Chokwe, however, was no match for the Salampasu as it was focused on plunder and prey. From then on, the Salampasu gave up some of their ‚Spartan‘ equality to establish permanent dynasties of rich families, accepting some degree of the Lunda centralized rule.

The spirit of resistance was not extinguished, on the contrary. The first European to cross their territory in 1903 became acquainted with their unpleasant guerrilla tactics. It was only in 1928-29 that a colonial official (Alfred Jobaert), well-known to Salampasu as a warrior and hunter, was able to establish the Kasai Compagnie in the region permanently. In 1935, a Protestant and a Catholic mission (Scheut) were allowed to settle somewhere, apparently with limited success, taking into account the little they could learn about Salampasu culture and their spiritual world.

Only shortly after independence, in the early sixties, the warrior organisation (mungongo) destroyed masks and dissolved. According to Pruitt, an anthropologist, the chiefs were the driving force because they wanted to strengthen their authority.

There are few of old cult objects in Western collections. But in 1975, Cornet registered an increasing production of masks. He explained the phenomenon with „growing demand“. Liz Cameron added in 1988: „… demand of the International Art Market“. She urgently demanded new field research as long as the last initiated eyewitnesses of the rich traditional Way of Life were alive. Did someone make this happen?

If you suspect that I have tapped a hidden ‘source’ all the time, you are right.

Elisabeth L. Cameron published an illustrated ten-page study of history, society, and culture: „Sala Mpasu Masks” (1988 in African Arts). It concisely summarizes the state of the art at that time.

Perhaps we have to use the term „traditional“ with greater caution, since the ‘way of life’ of the Salampasu was largely due to an environment into which they had immigrated before.

In a different place for example, a small hill tribe in the Hindu Kush (Afghanistan), the Kafirs mutated into a harsh warrior society under increasing pressure to Islamization since the turn to the 19th century. They became the horror of all travelers and neighbors. (G.S.Robertson 1896, Max Klimburg 1999)

I have to confine myself to a rough sketch, because I want to present two authentic objects of Salampasu now.

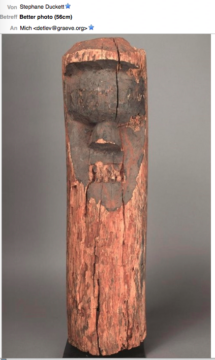

Fragment of a post with mask face

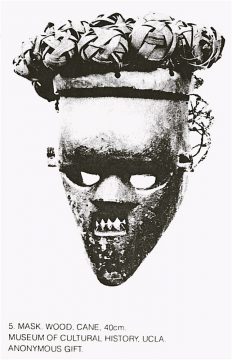

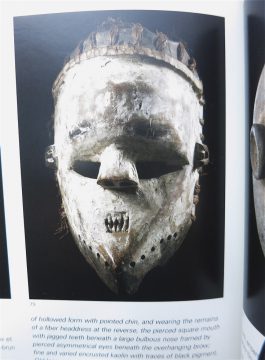

In May 2014, a 54 cm long fragment of a wooden stake was drawn from a container from Kinshasa with the face of a Salampasu circumcision mask. At first, its white and red split facial features were barely discernible under the cracked crust of kaolin but they became unmistakable under well-aimed lighting: everything was there, compressed in a narrow face oval adapted to the trunk:

In May 2014, a 54 cm long fragment of a wooden stake was drawn from a container from Kinshasa with the face of a Salampasu circumcision mask. At first, its white and red split facial features were barely discernible under the cracked crust of kaolin but they became unmistakable under well-aimed lighting: everything was there, compressed in a narrow face oval adapted to the trunk:

- the forehead curvature – interpreted as ‚male aggressive‘ among the neighboring Pende (Z.S.Strother)

- the wide slightly upturned nose

- and the square mouth with pointed teeth.

- The pole has a diameter of 16 cm, rounded at the top with a hollowed center. Today I think he could – like the corresponding masks – formerly

have been decorated by a headdress made of woven banana leaf balls. Below, the termite-eaten end had been transformed into decorative ‘honeycombs’ full of red earth.

have been decorated by a headdress made of woven banana leaf balls. Below, the termite-eaten end had been transformed into decorative ‘honeycombs’ full of red earth.

I wrote to Elisabeth Cameron in June 2014, and she promptly replied:

“From what I can see, this is a carved post that would have stood upright at the entrance to the men’s enclosure in the forest, not the the planks that form the edge of a dance enclosure. If authentic, it is quite rare. Would it be possible to get more information from your art dealer where he obtained it and from whom?”

I wrote June, 25th:

“I met the trader again last saturday. He will go to Kinshasa next week anyway and stay in the country for two month. He said he would meet there his Salampasu connection. He took a photo with him and accepted my ‘cadeau’ for the man, and was optimistic to get some information of village and circumstances of giving this post away.

Elisabeth Cameron:

“In the literature there are mentions of men’s enclosures in the forest secluded from women where posts and sculptures were displayed. (…) the hole in the head is common from wood sculptures that are left in the open. Water pools in the top of the and gradually the center of foot rots away. I’m interested in hearing more from the trader after he returns.

My answer September 7th:

“My man is back from the Congo, Kinshasa and Kuba regions. He couldn’t meet his supplier and informant Katambwe (originating from Kasai), because the man had left already for the mais campaign, he said. He put me off until Christmas. – Two Salampasu in Kinshasa told him, looking on the photo, that posts like this would be located in front of the circumciser’s place in the initiation compound to mark it.

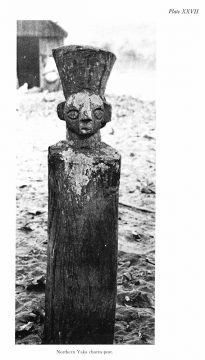

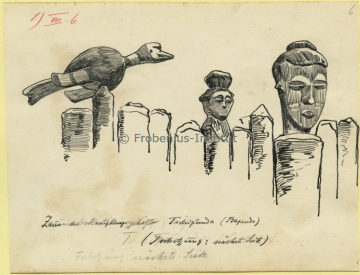

Of course we would have liked to trace the path of the object, but hardly succeeds, even with the good will of the last middleman. As a consolation, initiations and circumcisions in Central Africa have their laws. And the setting up of ritual pole sculptures at critical points such as processional ways and within the circumcision camp is not uncommon, as can be illustrated by posts of the Yaka (bourgeois), Pende (Frobenius), or Nkanu (LINK). By the way, they all carry the typical headgear.

Pin-up Busts à l‘Avantgarde

The first Notes I took

Squat, balanced, stable, strong.

Typical Salampasu facial scheme with rectangular aggressive small mouth and pointed teeth.

The two bodies consist of an upright head, a broad bosom and angular actively bent legs, large feet adhering to the plate, which looks like a perfect ramp for bouncing.

No details apart from the face, and the ornamental scars on the temples, just the pure posture: a rounded back, which passes seamlessly into the prone thighs – and pure forms: the breasts have a rounded diamond shape, below them there are block shapes.

Strength in the absence of supporting arms too. The stock neck (a short tube) seems to carry its load easily. The back of the head is rather drawn in.

This is not a Wotruba or Brancusi (LINK). This is not style, nor playing around with forms or individual obsession. ‚Form‘ is balanced by a message and a social role.

A few weeks ago I discovered this figurative stool in an otherwise rather dull shipment. Its seat had some time before been repaired. Its construction fascinated me from the first moment.

When human figures – predominantly women – wear or lift the seat, the stool becomes a caryatid stool. Among the Luba, the big neighbors in the northeast, karyatides were extremely widespread. On the art market you can almost call them ‚cultural ambassadors‘ of the Luba. Why not think of a more or less direct assumption of the real symbol of domination? The Salampasu as well as the Luba have similar founding myth, legendary tribal mothers. The stool could belong to representative of the lineage. But why not to a circumcisor of the mungongo in the fifties? He does’t look like being used extensively.

A whole circle of peoples around the Luba kingdom is called ‚lubaised‘. On this stool I see no aesthetic bond. I have never seen anything like this before. The sculpture is formally independent and radical; from the social angle it is realistic. Since I heard K. F. say “Atombusen” (‘Atomic Bust’), I’ve the heretical idea that the artist could have been inspired by some Belgian magazine title that had ended up in the Kasai; it would not have been the first time (see Yombé, 19th c.).

Women Power plus Tribal Power!

On the psychological level – I suppose – the design of the figures is typical of Salampasu women, or to say it bluntly: Women Power plus Tribal Power! That seems to be confirmed by the description of the Scheut missionary P.H. Bogaerts in „Salampasu, the Headhunters of the Kasai“ in ZAIRE, April 1950.

I have to admit: the Flemish text causes me problems. And I can not guarantee the correctness of the translations.

Bogaerts wrote on p.387/388 :

„Man and woman have not the least property in common. The man may not take anything from the woman, otherwise : Palaver. A word is quickly said : Divorce; the wife returns home or to her former husband, with whom she was already married; because a woman separates from husbands three or four times.

The Sala Mpasu does not believe in the loyalty of his wife. (De Musala Mpasu gelooft niet aan het getrouwheit van sijn vrouw)

That’s why, after a few months of marriage, he casually asks, „Tell me who you’re going into the bush with.“ If the woman does not want to confess, the man will not eat what she has prepared for him.

Or he forces her to speak, threatens her to take revenge. If she confesses, the man demands a fine from the men with whom the woman went, among other things. If his wife is not to blame, the man puts pressure on her to seek to woo and mislead one or the other young man.

Mutual insults accompany the divorce, for example, „That a bad disease (venereal disease) affects you, wherever you are.“ Or, „This God has sent you an incurable disease!“

Or: „That your mother gets the sleeping sickness, which should make her completely unrecognizable.”

This kind of insults inevitably cause divorce, sometimes forever, at least for a long time. If he wants to return to her, the man has to pay a goat to this ex-wife’s family.

When an infant becomes ill (mainly due to diarrhea), the woman decides that her husband has behaved badly, and he is obliged to admit it. If not, there is a big fight. The case ends with two poison tests on two chickens (a man’s and a woman’s chicken). If both remain alive or both die, a loser must try to find the guilty party.

“Close relatives by blood do not marry each other, due to a too close connection, …… “

UPDATE

An excellent summary of the Salampasu was given on 16 May 2019 to accompany a rare find, namely a post to an initiation enclosure which features a distinctive but simple face carved into the posts itself.

What I am about to describe is a very similar object but quite different in purpose.

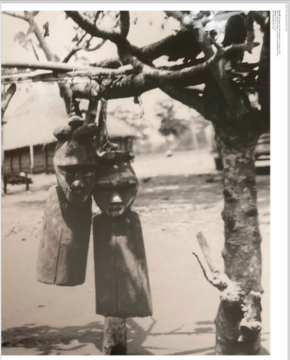

The Kalalaye post consists of a face with those easily recognisable but somewhat menacing Salampasu features carved onto a trunk measuring anywhere between 30 to 50 cm. Some are hollowed out to allow a rope to pass through for them to be suspended or occasional they are just placed on a rock within a small covered shelter.

According to A. Maesen (as cited in Volper 2014) these would be commissioned by childless couples and placed in front of their accommodation as an aid to fecundity.

They are called Kalalaye (or Tulalaye). Whilst there would be one Kalalaye commissioned per couple, numerous Kalalaye from different households could occupy one shelter. Kalalaye can also assist with other forms of illness for which a remedy is sought.

Bogaerts (Volper 2014) suggests that they might be representations of dead ancestors whose help is being sought to assist the living.

As with all matters Salampasu a dance is linked to the use of these objects -the Utumbu which had a direct therapeutic value as well as provide a link to the spirit world. The form of the dance was prescribed by the diviner would be assisting the couple.

Whilst one Kalalaye would be commissioned by the couple, they were problem specific therefore more than one Kalalaye might be required for more than one malady.

I have, as yet, not found reference to these posts beyond mid-century.“

I saw one of these stools with two women at the Barnes museum in philadelphia. The collection is a mixture of french paintings and greek, roman, and african art pieces. Thank you for the explanation.

Hello

I was fascinated by your account. I have recently read Julien Volper’s book which if you don’t have it I would recommend (I bought it through the Africa shop in Bruxelles.

I am in the midst of buying a post and would love to chat further with you.

Stephane